Trump's America and the rise of the authoritarian personality

Since the horror of Hitler’s Holocaust, psychologists have investigated why certain individuals appear more prone to follow orders from authority figures, even if it means that they have to sacrifice humanitarian values while doing so.

Apart from the Nazi regime, this issue is central to military atrocities such as the massacre in My Lai during the Vietnam war, and the systematic abuse of detainees in Abu-Ghraib prison in post-invasion Iraq.

But it also applies to civilian situations such as the recent unethical behaviour of some members of the US border control in the aftermath of Donald Trump’s executive order to ban Muslims entry to the country. Handcuffing a five-year-old child is not what you would necessarily consider “normal” human behaviour. Yet it happened.

While this issue has been debated on and off for decades, scientific research suggests that some people’s personality make-up gives them strong authoritarian and anti-democratic tendencies. That is, they either support or follow orders from authorities even when these orders could harm – or increase the risk of harming – other human beings.

After World War II, leading researchers, including Theodor Adorno and Else Frenkel-Brunswik at the University of California in Berkeley, were interested in understanding how ordinary German people could turn into obedient mass murderers during the Nazi genocide of the Jewish population in Europe.

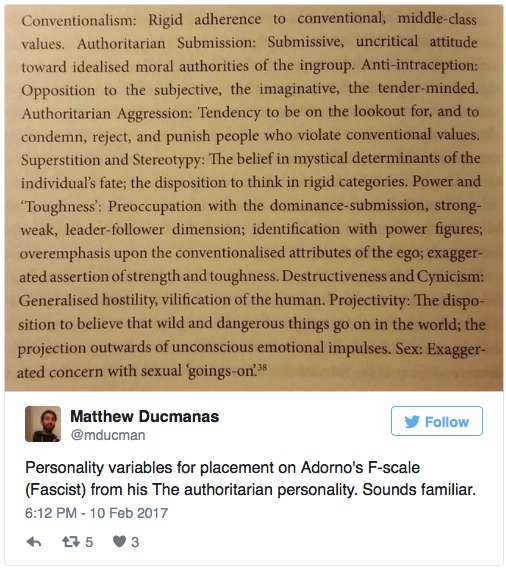

Using research on ethnocentrism as a starting point and basing their work on clinical studies, they built a questionnaire with the overall aim of mapping the antidemocratic personality. The scale, called the F-scale (F stood for fascism), focused on aspects such as anti-intellectualism, traditional values, superstition, a willingness to submit to authorities and authoritarian aggression. An individual scoring highly on the scale was labelled an “authoritarian personality”.

Unfortunately, the F-scale turned out to be methodologically flawed which limited its use for understanding authoritarianism.

Racist, sexist, aggressive, gullible

In the early 1980s, Bob Altemeyer, a professor at the University of Manitoba, refined the work with the F-scale and came up with a new definition of the authoritarian personality. Altemeyer renamed the authoritarian personality “right-wing authoritarianism” (RWA) and defined it as having three related dimensions. These were: a submission towards authorities, endorsement of aggressive behaviour if sanctioned by authorities, and a high level of conventionalism – that is conforming to old traditions and values.

Among antisocial traits and attitudes investigated in psychology, RWA definitely ranks high up the naughty list. Right-wing authoritarians are, for example, more racist, more discriminatory, more aggressive, more dehumanising, more prejudiced and more sexist than individuals with low RWA. They are also less empathic or altruistic. Another downside is that they tend to think less critically, instead basing their thoughts on what authority figures say and do.

Research findings also suggest that those with high RWA are more likely to follow unethical orders. For example, in a replication of the famous Milgram obedience experiment in a video environment, high RWAs were found to be willing to use more powerful electric shocks to punish their subjects.

Scoring high on RWA is theoretically in line with the anti-democratic personality suggested by Adorno and his colleagues. A plethora of studies shows that people with these traits are more anti-democratic – for example, they tend to support restriction of civil liberties and surveillance, capital punishment, the mandatory detention of asylum seekers and the use of torture in time of war.

Threat to democracy

So can RWA pose a threat for a democratic society? The answer is generally speculative, but at least hypothetically the answer could be yes. Some indications of its potential danger can be found in the following fields of research.

A study on university students has shown that the level of authoritarian attitudes is significantly higher immediately after a terrorist attack than during a non-threatening condition. This supports findings from longitudinal research showing that RWA increase when the world is perceived to be becoming more dangerous.

How such reactions relate to people’s political choices has suddenly become very relevant. Researchers interested in understanding destructive political leadership suggest that one must look at how environmental conditions, the followers and the leader interact with each other. This is what is referred to as the toxic triangle – a society with a high degree of experienced threat, a narcissistic or hate-spreading political leader and followers with unmet needs or antisocial values is at risk of adopting a destructive political course.

So it’s unsurprising to hear that authoritarianism was found to be one of the factors statistically predicting support for Donald Trump before the recent US election.

Not only this but experimental data suggest that those displaying high RWA are more prone to be supportive of unethical decisions when they are promoted by a socially dominant leader – that is, a leader viewing society as a hierarchy in which domination of inferior groups by superior groups is legitimised.

Researchers in this area have suggested that individuals scoring high on RWA, and other antisocial traits and attitudes, are more likely to choose occupations in which the opportunity to be abusive to others might arise. Based on this reasoning, one could expect that soldiers and police officers should have a higher level of RWA than comparison groups. And this appears to be borne out by research that suggests that both soldiers and border guards have higher levels of RWA in comparison to the rest of the population.

How these findings relate to actual abusive behaviour remains to be investigated in future research. But the idea of having people with these traits guarding a democracy seems to me to be something of a contradiction in terms.

Magnus Linden, Senior Lecturer in Psychology, Lund University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.