Resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act Gives Sanctuary Cities a Model for Resistance

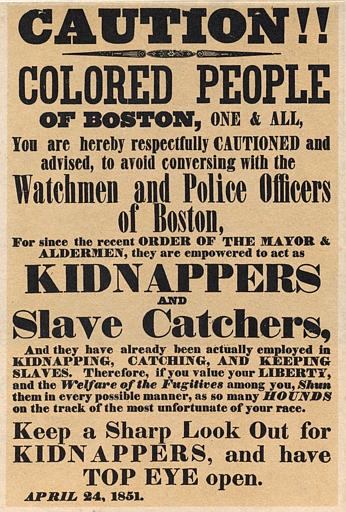

An April 24, 1851 poster warning the "colored people of Boston" about policemen acting as slave catchers.

Lawsuits over the executive order that barred entry from seven predominately Muslim nations dominated the news in recent weeks. To less fanfare, local governments in San Francisco, Santa Clara County, and Massachusetts filed lawsuits hoping to see President Trump in court concerning another executive order—one that seeks to coerce local participation in immigration enforcement by starving the sanctuary cities of federal funding.

Anti-sanctuary agitators regularly claim that sanctuary jurisdictions defy federal law, and some (most recently Karl Rove) go so far as to suggest that cities and counties that seek to disentangle themselves from federal immigration enforcement are morally and legally equivalent to the slaveholding South.

But while sanctuary policies can express disagreement with federal policy, this does not make antebellum nullification their historical progenitor. Closer analysis yields a more meaningful historical analogue, between sanctuary cities and those northern communities that resisted fugitive slave recapture.

By enacting anti-detainer policies, sanctuary cities seek to disrupt a pipeline by which humans are fed from local criminal systems into the immigration enforcement system. The transfer of prisoners is accomplished with pieces of paper (“detainers”), requesting that local authorities prolong prisoners’ detention and eventually turn their bodies over to federal immigration authorities.

As I have written elsewhere, the grim details of this “crimmigration” pipeline (the “delivering up” or rendition of human bodies through paper transactions), its racial architecture (compounding the disproportionate racial impact of local criminal justice systems and the disproportionate racial impact of the immigration enforcement system), and the profits from the immigration detention leviathan fed by the crimmigration pipeline (fueled by a Congressional mandate that 34,000 detention beds be available each day), all reinforce the analogy between immigration rendition and fugitive slave rendition.

Sanctuary cities share with their abolitionist forebears a deep moral commitment to liberty and equality. And, when it comes to legal theory, sanctuary policy is rooted not in the nullification theory popular in the slaveholding South, but rather in the Tenth Amendment’s prohibition on federal “commandeering” of local government. This anti-commandeering argument similarly underlay the “personal liberty” laws passed in northern states to disentangle them from the slave rendition machinery.

Sanctuary cities’ resistance to immigrant rendition, like northern resistance to slave rendition, takes place in that part of the law that is reserved for local action and upon which the federal government cannot intrude. A Third Circuit decision in 2014 reaffirmed this point, holding that a Pennsylvania county could be held liable for the wrongful detention of a U.S. citizen pursuant to an immigration detainer. The court rejected the county’s argument that its participation in immigration rendition was compelled by the federal government.

Sanctuary policies are also rooted in the Fourth Amendment. A federal court in Oregon held, also in 2014, that the detention of a local prisoner based on an immigration detainer violated the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition on unreasonable seizures. In other words, the federal government, through detainers, was asking local governments to violate the Constitution.

The 2014 decisions and others that followed fueled the wildfire spread of sanctuary city ordinances across the nation, as jurisdictions hastened to follow—not nullify—federal law. Ultimately the uproar caused the Obama administration to abandon its premier interior enforcement program, “Secure Communities.”

The legal and moral ancestry of the sanctuary city can be found in the antislavery movement. But being on the right side of history does not mean sanctuary cities will be able to protect their residents.

Ultimately, because northern states could not be compelled to participate in slave rendition, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, creating a vast federal rendition machinery to do what the North would not. This history—no matter the outcome of the sanctuary lawsuits—may tell us where we are headed.

The Trump administration has promised to revive the Secure Communities program, describing it, contrary to all available evidence, as “popular and successful.” And Trump’s executive order of January 25, true to his campaign promises, envisions a massive federal “deportation force” unbounded by any real enforcement priorities. Immigration raids in so-called sanctuary cities, like the one unleashed in Los Angeles the evening of the Ninth Circuit’s decision striking down the travel ban, may become all too routine.