FROM OUR ARCHIVES The American Press Has Served Us Well. We Need to Protect It.

At a time when casual TV viewers are being suddenly hammered with Presidential slurs and slanders directed frontally at our Press, Dr. Bornet has sat quietly in his retirement home apartment and summed up what newspapers have done for him. They served him as boy, youth in uniform, when getting that Stanford history doctorate, as college instructor, author, editor, and active retiree.

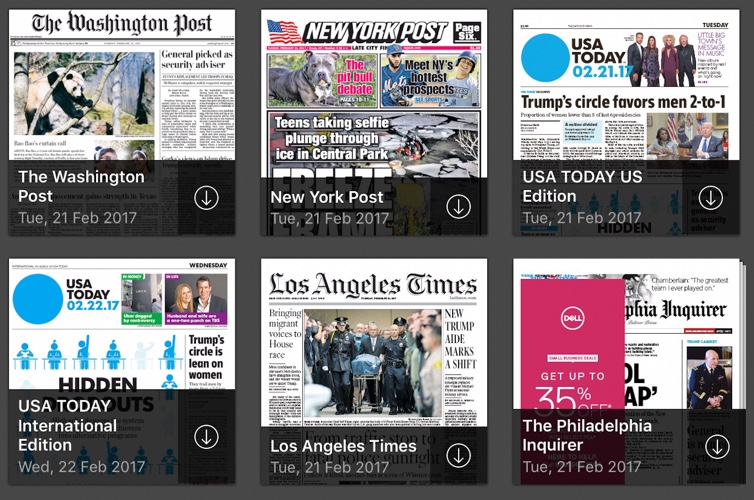

As I have listened to the continuing diatribes from on high against “the Press” and “you guys” beginning toward the close of our recent national election, and as I watched, astonished, as the attack dog posture continued from the White House and hustings well into 2017, this lifetime historian decided to offer an ameliorating opinion or two about newspapers.

Writing when very old, I

think it safe to say that “newspapers have been vital to my

rational and balanced life.” It is American newspapers I mean, of

course. I am aware that my dear friends in England have profited from

their Times, Telegraph, Independent, and

whatever; I have been present when they demonstrated how much the

London press has meant to them during years of enormous stress. My

focus, however, is on the reputation of the American press, going

forward.

Writing when very old, I

think it safe to say that “newspapers have been vital to my

rational and balanced life.” It is American newspapers I mean, of

course. I am aware that my dear friends in England have profited from

their Times, Telegraph, Independent, and

whatever; I have been present when they demonstrated how much the

London press has meant to them during years of enormous stress. My

focus, however, is on the reputation of the American press, going

forward.

I am going to take readers quickly through a lifetime of my newspaper reading, so get ready. We’ll start in the 1920s and come up to today; we’ll begin in Pennsylvania and meander through a number of our states until we reach Oregon. Beginning as a boy and youth, today’s newspaper reader (who is writing) will emerge as an experienced old man, indeed.

I delivered the Philadelphia Public Ledger on our street in suburban Bala Cynwyd when in 3rd grade. Doing so meant that I began a lifetime of reading the comics back with Orphan Annie and Popeye. I never stopped. (And I made a few valuable dimes.) Today I realize that the “light touch” I picked up from my introduction to work molded my entire attitude toward Life and my future interaction with burdensome phenomena. Those daily comics were casual, possibly, but the Sunday ones were substantial. Both taught me “stuff” that was worthwhile. Never have I viewed life in the final analysis as anything analogous to the serious “life and death” so many accept with ultra-seriousness. For a youthful year I delivered the Main Line daily paper, growing aware that big cities don’t have a monopoly on the news people seek out.

I worked as a major morning newsboy for the Miami Herald after we went broke in the North and moved South. I was a young businessman, delivering hundreds of papers from 1933 to 1935 to always kind and almost entirely Jewish subscribers on lower Miami Beach. I read quite a bit in the papers I delivered, so that that world out there was something of a familiar place by the time I finished high school. I had read news of alien peoples from overseas; I had been aware of two national elections though too young to vote. “Sports” was not a single activity, and it had been normal for me to join our tennis team (trying to emulate Bill Tilden).

Off to Atlanta, Georgia for five years, then one in Athens, I joined the readers of the Atlanta Journal which “covered Dixie like the dew,” a phrase it sang on late night radio’s WSB at signoff as I studied at Emory and the University of Georgia. By 1941 I had learned from the daily newspapers that the terrible war that began in September 1939 was surely going to sweep me into it sooner or later. A History major, I and my intimates had no doubts (but when it came to us and I was deeply on “active duty” first as enlisted man and then an officer, it was time for the Miami Herald again to tell me “what’s what” and “how are we doing?”).

I was separated from news in 1942 when in a Navy school in Quonset Pt., Rhode Island and still uninformed for two months in distant San Diego later on, but then as luck would have it, I was about to be transferred. I would become a reader of the Oakland Tribune or San Francisco Chronicle until war’s end in 1945. During that awful yet finally victorious year 1944-45, the Trib was a paper sometimes focused on Berkeley’s majestic University of California and my Naval Air Station, Alameda. It tried to tell this air station Barracks Officer his chances on whether the war would get to kill him—or not.

Postwar it was time to read the Macon (Ga.) Telegraph as a way of getting familiar with racial segregation and discrimination. (I wrote columns in those months for that venerable paper, quite watchful over “how I put things” for the natives.) The newspapers I came to read in postwar America were supposed to get me ready for the big leagues of serious university study. For two years I was hard working on the beginning faculty of the University of Miami in Florida. Then it was Stanford University, dragging my family along. Then, when I could, I read the San Francisco Chronicle and Examiner and the Palo Alto Times.

Stanford was about to focus me on Russia, early centuries in England, and every possible aspect of United States history. Every day for a little while it was the newspapers that made sure I knew about growing tensions in Asia. This Commander in the USNR relied on the press to keep him accurately informed. As I did two weeks duty over and over after World War II I counted on newspapers to inform me with integrity—and they did what they could.

Those San Francisco and Palo Alto papers did their duty for me until 1957, when scholarship and supporting a family led me to the huge Chicago Tribune and the city’s Daily News. The former boasted a readership in five states. It had shrugged off its election fiasco of publishing on page 1 a giant photo of Harry Truman holding up the headline DEWEY BEATS TRUMAN—an unparalleled fiasco in 1948.

In 1959 this Bornet would abandon his history editorship at the Encyclopaedia Britannica and creative work for the American Medical Association and join The RAND Corporation in Santa Monica, California. Now it was the turn of the giant Los Angeles Times that took over control of family perceptions. Years earlier (1953 to 1956) he had created a huge book on California Social Welfare for the Bay Area’s Commonwealth Club. Now, he would commute downtown on Fridays to L.A.’s Town Hall. He and his son would get to be pictured on page 1 of the local Santa Monica paper after winning the open ocean sailboat race on July 4. It was a great reason to be featured.

They say that all good things come to an end, and so it would prove for those then expecting to make Santa Monica a permanent home. January 1, 1963 I reported to the president of Southern Oregon College for a permanent life in distant and remote Ashland, Oregon as Professor of History and Division Chairman. The location was 290 miles from Portland’s Oregonian and even farther from the San Francisco Bay area. A choice of reading orientation had to be made. It would be The Oregonian from remote Portland. But wait! There was a Medford Mail Tribune and even an Ashland Daily Tidings! The second two would be read, unbelievably, from 1963 to 2017, and beyond. The big city paper, read statewide, was an indispensable adjunct to citizenship in the state of Oregon for the coming 60 years, though published mountains and valleys away. It was indispensable to the adult Bornets as they tried to maintain good citizenship as caring Oregonians.

Because I was teaching “problems” courses of various kinds every summer as a Professor, I felt a need to be better informed than anybody else! Almost on the first day in that remote, mountainous environment, I subscribed by mail to the New York Times. Reading its columnists quickly became routine, as I struggled to keep the thick papers from piling up in a study corner. (Years earlier, at Stanford, I had read virtually all serious news in the Times for the 1920s, shelved deep in the only somewhat lighted university Library.) That metropolitan paper still deserved the label “friend” as Beth and I prepared in 1969 to circle the world for four months on the vessel of the World Campus Afloat. Remote Africa and South Asia began to open their secrets to us—so long a parochial audience on world religion and life in other cultures.

Returning, it was back to those newspaper pages we relied on. After a major heart attack, the years of recovery were given over to the Christian Science Monitor, a lighter but reliable daily effort originating in Boston.

Meanwhile, my daughter came to read Hawaii papers, and my son the New York City papers (even working for the Daily News for a time). Earlier, that young man had read the Eugene Register-Guard over a split four-year period divided by service in the Vietnam war. Prepared in journalism, he served as editor of the carrier Yorktown’s newspaper with an office below the huge deck.

During the better part of a century it was newpapers that offered the Bornets the facts and names that made citizenship possible. When illness took Mrs. Bornet, the author entered a retirement home and began four years (so far) of the Wall Street Journal arriving at his door. Never had he been offered a daily look at finances as part of the news to begin the day.

Meanwhile, that county paper kept coming, a good thing, for he was still a citizen. What kind of individual hoped to be his county commissioner? Mayor? State representative and senator? Light was cast on measures to be added to state constitutions. Sports were made meaningful. Investments could be kept track of, and a changing world announced itself in print.

As an active local resident, Vaughn wrote innumerable letters to the editor in those decades, urging action (or inaction), supporting officials and neighbors, and urging points of view on controverted subjects at home and abroad.

Without a Free Press, one with integrity, that mostly “meant well” and offered a mountain of facts and figures on people and places—and ideas of all kinds—this family could never have maneuvered its way through a lifetime in Pennsylvania, Florida, Georgia, California, Illinois, and Oregon. It would have been hard without a doubt. And illusion would have displaced reality.

The reader should think about some of these generalizations and consider them a composite message worthy of remembering. When some at this time slur the press and “those writers” and try to leave an impression that A Free Press is not all that important—or even possible (!)—do return to fundamental truths that have long served.

Nobody said all those writing for newspapers are “fair” or “balanced” or necessarily “careful” to the point of perfection. But those working for the American press at every level, it is fair to say, have been pretty much lined up on the side of decency, accuracy, care, and overall, responsibility—at least as I think about it after nearly a century of interaction.

My life, needless to say, 1917 to today, could never have been lived in comparable style without never ending access to big league newspapers. They were worth buying and reading with enjoyment, pleasure, profit, and edification—that is, never ending improvement to one’s mind. I cannot imagine life traversing schooling, work, recreation, and interaction with people and governments without the press: the one indispensable factor under discussion.

The American free press in its many forms, aspects, and showcases is not to be taken for granted. TV’s news efforts emerged from after World War II. Internet news is a Johnny-come-lately and seems ready, even overdue, for agreed on creative standards. The internet crews must live up to the standards painstakingly worked out over the years by the nation’s daily newspapers.

There is no pretense here that the press in my day was “unbiased,” or “fair,” or “objective” as a goal or in universal result. Yet its major practitioners took journalism courses as a rule, were taught to “try” for fairness, and had been lectured on avoiding “bias.” Some newsmen and, increasingly, women rose to the heights; a few reveled in forms of revenge or carelessness. (It was those practitioners who chiefly upset our new President as he ranted—and generalized—his way into the new year and its nearly overwhelming responsibilities.)

This is no time to relax and laugh and hope for the best. A lot’s at stake. Commentators surveying the situation of President versus Press bear the burden of real shock. As a TV viewer (among other things) I have come quickly to realize that democracy and our republican conduct could actually come to be at risk. If we ever needed to seek out, treasure, and nurture our highest standards, trying harder, it is now. Raw charges hostile to our press must be repudiated—even scorned. Those enjoying and maybe even profiting from such a posture need to be reprimanded and contradicted.

You are entirely welcome to join this lifetime newspaper reader as he begins yet another year of inviting publishers, editors, newsmen and women, and the entire apparatus of “the media” as it seeks to maintain itself in prime condition. Remember always that gathering and distributing the news is a professional activity. Its standards are not unknown, nor are they out of date. They do, however, need to be kept in mind daily by one and all.

Above all, the press in its now extended form needs all of us to step forward and protect what was so very hard to create in the first place over several centuries. Let’s all agree that a free press is worth fighting for. That new man in the White House needs to be made aware that the job he occupies is a Bully Pulpit—and not a Bullying Pulpit.