Where Are All Those Women Trump Said He Loved?

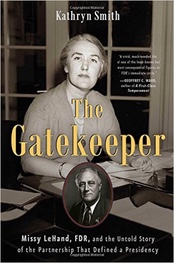

Missy LeHand (center front) surrounded by her female White House staff, 1938. Source: Library of Congress

As president of the United States, Woodrow Wilson typed his own letters. His secretary, a man, functioned as a sort of chief of staff, but there wasn’t much White House staff to be chief of. Women didn’t get the vote until 1920, but that didn’t stop Wilson’s wife, Edith, from running the executive office after he suffered a debilitating stroke in 1918. She’s been called the first woman president.

Women

who didn’t happen to be married to the president have had a steep

climb when it comes to attaining key positions in the executive

branch of government. While campaigning last summer, Donald Trump

insisted, “I cherish

women. I want to help women. I’m going to be able to do things for

women that no other candidate would be able to do, and it’s very

important to me.” Yet he’s found precious few women to appoint to

positions of power in his administration.

Women

who didn’t happen to be married to the president have had a steep

climb when it comes to attaining key positions in the executive

branch of government. While campaigning last summer, Donald Trump

insisted, “I cherish

women. I want to help women. I’m going to be able to do things for

women that no other candidate would be able to do, and it’s very

important to me.” Yet he’s found precious few women to appoint to

positions of power in his administration.

In fact the gender representation in Trump’s administration is the worst since the days of Jimmy Carter, when they held just 11 percent of the cabinet-level positions, according to the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University. The center, which studied appointments from Franklin Roosevelt forward, pegged the percentage of women in the 23 cabinet-level positions of the fledgling Trump administration at 17. (A recent analysis by USA Today found that women have been appointed to just 23 percent of 70 important positions.)

Trump’s White House disagreed that the president is ignoring talented women, pointing to the important role of senior advisor Kellyanne Conway, who was the last of his three campaign managers, and the influence of his daughter Ivanka, who has his ear but does not have a paid staff position. His other cabinet-level female appointees are Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, U.N. Ambassador Nikki Haley, Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao and Linda McMahon, head of the Small Business Administration.

Yet the white maleness of Trump’s cabinet is somewhat startling compared to the diversity of the cabinets of Barack Obama, George W. Bush and, especially, Bill Clinton. The Center for American Women in Politics calculated the appointments of women at 30 percent in Obama’s first term, 19 percent in Bush’s first term and 32 percent in Clinton’s. The percentages grew substantially for all three presidents in their second terms, with Clinton reaching an all-time high of 41 percent.

Bush’s first term A-team was noteworthy in that he had three very powerful women in the West Wing: Karen Hughes as counselor, Condoleezza Rice as national security advisor and Harriet Miers as White House staff secretary. Bush biographer Jean Edward Smith wrote that “nothing came to his desk that Hughes had not seen,” describing her as his “confidante and alter ego.” A similar role was filled by Obama’s senior counselor Valerie Jarrett, who was also described as the first family’s “first friend.”

How did we get from a president who typed his own letters to a White House to women in key advisory roles (or not)? As with so many situations in modern government, we should look back to the presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt to see when women got a significant toehold. He appointed the first female cabinet member in U.S. history, Frances Perkins, at the Department of Labor. (She was one of only two cabinet secretaries who lasted throughout FDR’s 12 years in office; the other was Harold Ickes at the Department of Interior.) She served with distinction, leaving fingerprints on such New Deal creations as the Social Security Act, the Civilian Conservation Corps, and the minimum wage law.

FDR’s administration boasted other high-profile women appointees, notably his private secretary Marguerite A. LeHand, the first female private secretary to a president, who gradually became what we think of as chief of staff today. (The title was not used until the Eisenhower administration.) Because LeHand lived in the White House and was on call around the clock, she also exerted quite a bit of influence as an advisor and confidante. After poor health forced her resignation in 1941, her assistant Grace Tully stepped into her shoes as private secretary to the president. There has not been a male private secretary to a president since.

Other important female appointments in FDR’s executive branch were Nellie Tayloe Ross, who became the first female director of the U.S. Mint, and Josephine Roche, assistant secretary of the treasury. Eleanor Roosevelt’s influence was definitely felt, with a number of capable women being appointed to key jobs within New Deal agencies, writes David Woolner, Senior Fellow and Hyde Park Resident Historian of the Roosevelt Institute. He says the record of the New Deal would not be matched in a presidential administration until the 1960s.

Indeed, no women had cabinet-level positions in the administrations of John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson or Richard Nixon, according to the Center for American Women and Politics. Gerald Ford broke the ice by returning a woman to the cabinet room when he appointed Carla Anderson Hills as secretary of housing and urban development.

Trump still has a good many spots to fill in his administration. Perhaps he’ll run across some of those “binders of women” Mitt Romney talked about and will find a few who are worthy of appointment.