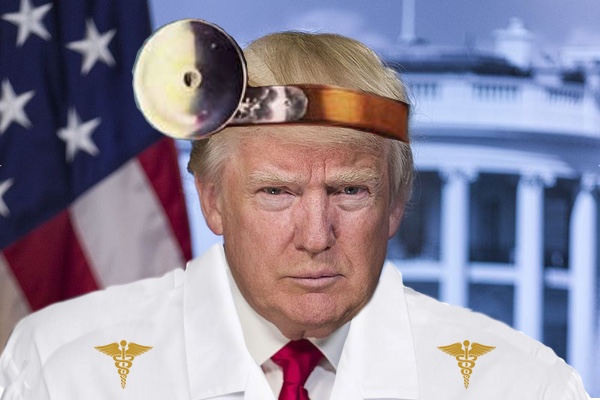

“Trumpcare” – A Word Democrats Can Learn to Love

Just hours after Republicans presented their plan to repeal and replace Obamacare, Democratic Senator Chuck Schumer criticized “Trumpcare.” Borrowing an idea from the Republican’s messaging strategy, Schumer offered a clever one-word characterization of the GOP’s insurance proposal. For years, Republicans had been blasting Democrats’ proposals for health care reform in language that personalized the issues. They referred often to “Hillarycare” and “Obamacare.” Now Democrats have a related opportunity. They can stress President Donald Trump’s ownership of the GOP’s controversial new insurance plan by labeling it Trumpcare.

Since the 1990s, Republicans have employed the technique with great effect. They associated the Clinton Administration’s health proposals in 1993 with leadership by the First Lady. Resistance to Mrs. Clinton’s role in leading the reform effort played an important role in the huge gains Republicans made in the 1994 congressional elections. In a related way, GOP efforts to attach Obama’s name to the Democrats’ health care plan of 2009 contributed to broad Republican gains in the mid-term elections of 2010. Democrats may discover that calling the GOP’s American Health Care Act “Trumpcare” assists their fight against that plan and boosts their party’s prospects in the 2018 congressional races.

Academics and journalists have noted the effectiveness of simple, personalized references to health care legislation, evidenced in the GOP’s frequent references to Hillarycare and Obamacare. These terms suggested that a powerful individual at the White House forced her or his personal vision of reform upon the American people. Critics of Hillary Clinton’s leadership argued that the First Lady was not an elected official. She was overreaching when heading a panel that designed major legislation behind closed doors. By invoking “Obamacare,” Republicans created an impression that Big Brother in Washington acted in an authoritarian and paternalistic manner. References to Hillarycare and Obamacare also excited reactions from Americans who distrusted Mrs. Clinton and President Obama. Polls showed, for example, that individuals surveyed had a more favorable opinion of the Affordable Care Act when they viewed information about it that was not associated with Barack Obama.

The term Hillarycare was just a small factor among many that contributed to the Clinton Administration’s defeat. Resistance from powerful interests in the health care industry made a huge impact. Lobbyists for doctors, hospitals, and Big Pharma opposed the plan. The Health Insurance Association of America was especially effective in stirring doubts. The Association’s “Harry and Louise” ads on television showed a middle class couple struggling with the Clinton plan’s bureaucratic complexity.

References to “Obamacare” were a much more prominent feature in the GOP’s resistance to major health care legislation in 2009. The term Obamacare did not originate with Republican spin doctors. Journalists began to employ the word as a shorthand reference to the awkwardly named Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. That legislation was the work of many people in Washington. President Obama championed the cause, but congressional leaders and others worked out the specific details.

GOP leaders quickly recognized the value of identifying the Affordable Care Act with Obama. Mitch McConnell, director of GOP resistance in the Senate, denigrated “Obamacare” often in his speeches. George Lakoff, a professor of cognitive linguistics at the University of California at Berkeley, warned about the power of language. Lakoff showed how clever “framing” influences voters’ judgments. He noted that “Obamacare,” communicated an impression that President Barack Obama was personally responsible for the legislation. If Americans had complaints about their experiences with the nation’s health care system, they could blame Obama.

President Obama did not loudly protest the GOP’s use of the term even though he recognized the purpose of Republican messaging. By 2013, it was clear that “Obamacare” was enmeshed in the nation’s vocabulary. There was no easy way to fight it. So Obama chose to embrace the appellation. During a speech in Maryland, he used the term 13 times. “Once it’s working really well,” said the President humorously, “I guarantee you [the Republicans] will not call it Obamacare.”

Now that Obamacare is in danger of dismemberment, it is attracting new admirers. Millions of Americans are fearful about losing benefits. At boisterous town hall meetings citizens with troubled medical histories angrily criticized Republican legislators who supported repeal. Opinion is shifting from complaints about Obamacare to complaints about the GOP’s American Health Care Act. Many citizens worry that guarantees of insurance under Obamacare will be replaced by a less generous program of “access” to health insurance. Millions of poor and middle-class Americans could lose coverage. Opposition to the GOP’s plan is also shaping up from organizations representing doctors and nurses, hospitals, and the AARP.

Political resistance to the Republicans’ health proposal lacks a simple rallying cry. Democrats need a brief, emotion-laden term that symbolizes their objections. Ironically, over the course of recent American history Republicans revealed a successful strategy for resisting controversial health insurance legislation. If Democrats follow Chuck Schumer’s example, which stressed Donald Trump’s ownership of the health bill, they may be able to throw obstacles in the Republicans’ legislative path and improve the Democratic Party’s chances in the 2018 mid-term elections. A campaign against “Trumpcare” might deliver rich political rewards.