Betsy DeVos Is Making the Same Argument Critics of Public Education Have Been Making for a Century

President Donald Trump’s budget has met less than universal acclaim. In the area of education, the budget cuts over $9 billion from the previous budget, a decrease of 13 percent ($1.4 billion of which will be earmarked to expand school choice). Some federal programs will be reduced, but over twenty will be eliminated entirely. Among those on the chopping block are arts education, foreign language education, after-school programs, professional development for teachers, Alaska and Hawaii native programs, and others that, according to the budget, are ineffective or could be funded through other sources.

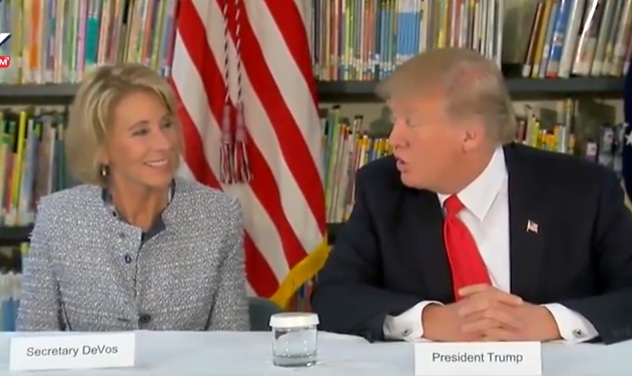

Betsy DeVos, Secretary of Education, attempted to defend the education budget to a House appropriations committee. From the discussion at that meeting, it is obvious that there are several huge problems with the Trump/DeVos budget—including a rollback of protection for students facing discrimination (due to disability, race, religion, or anything else) from federally-funded private schools—but the program cuts call to mind an issue that has been part of the history of American education for well over a century: the expansion of the curriculum beyond the so-called three R’s (reading, writing, and arithmetic) to include social studies, science, foreign language, art, physical education, and more. Many people (including Betsy DeVos) have seen these classes as “fads” and “frills.”

In the early nineteenth century, Horace Mann was a proponent of such expansion, partly because he thought of education as the “great equalizer of the conditions of men—the balance wheel of the social machinery.” Later, John Dewey’s notion of “progressive education” pushed this even further. There was more to Dewey than curriculum matters, but opposition to the fads and frills of modern education is what united most of his many critics.

By the early twentieth century, this was a hot issue. In 1923, a survey of New Jersey’s school superintendents showed that 13 percent favored the omission of such courses as modern languages, music, home economics, and “physical training.” The state’s education department, on the other hand, supported these courses. “The great purpose of education,” it said, “is to mold a school curriculum which will give to the boys and girls equality of opportunity, create in them worth of character, and best prepare them to meet their country’s needs.”

A couple years later, John C. West, president of North Dakota University, made the same point: “ ‘Fads’ and ‘frills,’ which have been so roundly abused, may solve the problem of delinquency among our young people who will soon take over the guidance of civilization. Perhaps they will be taught to spend their leisure time to good advantage. In the absence of other agents of social control, public education must accept a new function.”

This was part of the context in which Willis A. Sutton became Atlanta’s school superintendent in 1921, a position he held until 1943. In the 1920s, Georgia’s economy was already suffering from the economic depression that would hit the rest of the nation a decade later, and the state and municipal budgets were hurting. Atlanta’s civic and business leaders pushed to cut the schools’ music, art, elementary science, kindergarten, and physical training programs as a way to save money. Sutton, a believer in progressive education, opposed retrenchment. Through the 1920s, and to a lesser degree during the 1930s and early 1940s, he fought these reductions, arguing that the problem was not too many frills but too little financial support.

In 1923, William Gaines, president of the Atlanta school board, and Sutton discussed the situation with the city council. They argued that while Atlanta’s city charter required the city to give at least 26 percent of its revenue to the schools, the amount could and should be more. The current level of spending worked out to $46 per student, they said, while the national average for cities of Atlanta’s size was over $66 per student. Gaines asked the mayor if he would support an increase in the school board’s share of city revenue. The mayor replied, “26 percent will be enough if you cut off the frills.”

According the Atlanta Constitution’s report of the meeting, the mayor’s remark “brought Superintendent Sutton to his feet with a trace of feeling.” Sutton’s response is worth repeating:

The Atlanta schools have no frills. If by frills you mean kindergartens, I tell you they are not frills; they are necessities in education made so by popular demand and the conclusions of the best educators in the world. If by frills you mean music in the schools, then an expression of human emotion that antedates speech is a frill; if by frills you mean art, the kind of art we teach in the schools, then every use to which trained hands are put are frills …; if by frills you mean physical education, then the human body itself and the very perpetuation of the race are frills. Education is for more than to teach people to read and write; it is to teach them how to live, for their own happiness and for the development of all mankind.

(As the meeting ended, a city councilman said that “public schools are coming to take the place of parents to the point of ruining the family, the most important of all institutions,” a very DeVosian statement.)

At one point, according to the newspaper report, Sutton said that “a campaign had been waged against ‘frills in education,’ which, he declared, was directed … against the common people through the fear that if the masses learned through the schools to enjoy art, music, and the better things in life, they would demand higher wages.”

Sutton and the board held the line, refusing to cut programs. Teachers supported him; in 1933, they even agreed to a 16 per cent pay reduction rather than cutting programs. That same year, the state legislature amended Atlanta’s city charter, requiring the city to give at least 30 per cent of its annual revenues to the schools, an increase that got the schools, barely, through the worst years of the Depression.

Historian Philip Racine held that Willis Sutton was a model of the progressive school superintendent. Racine quoted a speech Sutton made to the National Education Association in 1924 in which explained what kind of man a school superintendent should be: “He must be tactful, but it is of even greater importance that he be fearless. . . . In this age when demand after demand is being made for retrenchment in education, where plutocratic industrialism is trying to create a plutocracy among educators, when the fictitious increased cost of education is being flaunted, when men and women are declaring that the salaries of teachers must be cut, and that whole departments must be cut out, the prime essential of a superintendent . . . is the bravery to stand before his people and display an unyielding courage by demanding the best and the highest things for his teachers, his officers and supervisors, and the children of his city.”

“Plutocracy” means government by the wealthy. It seems we have circled back to where we were almost a century ago.

Facing Betsy DeVos and an administration that seems not to care for the nation’s public schools, we need superintendents who are fearless. As we look at education policies that benefit the wealthy and harm the rest, we need superintendents who will display an unyielding courage. If we are going to return to the concern in the 1920s over fads and frills, we should also return to superintendents and other educational leaders who will fight for an educational system that will benefit all Americans.