What the Trump Administration Is Proving Is the Importance of White House Staffs

The president’s chief female advisor wore an outrageous look-at-me-red-white-and-blue ensemble to the inauguration, spouted “alternative facts” on cable television news shows and was photographed in an embarrassing splayed-leg crouch on a sofa in the Oval Office.

His press secretary

berated the members of the media so belligerently that he was

lampooned on Saturday Night Live as shouting down a female

correspondent with the help of a leaf blower. The president was so

enraged about his press treatment that he loudly considered ending

press briefings.

His press secretary

berated the members of the media so belligerently that he was

lampooned on Saturday Night Live as shouting down a female

correspondent with the help of a leaf blower. The president was so

enraged about his press treatment that he loudly considered ending

press briefings.

His chief political strategist’s wacky-right theories were profiled in a cover story in Time Magazine (with a close-up photograph that would give nightmares to small children) titled “The Great Manipulator.” The president was ticked off that an advisor who joined his campaign late in the game was hogging the spotlight.

The chief of staff and vice president? Who knows what, if any, influence they wield over Donald Trump?

At the top, the man who likes to brag about his “very good brain” but is obviously sorely lacking in most every other faculty needed in a president, listens most closely to his daughter and son-in-law. Meanwhile, there is so much jealousy, discontent and in-fighting among the staff that the seat of the executive branch leaks like a big white sieve.

Oh, for a leader with a “second-class intellect and a first-class temperament.” Oh, for the White House staff assembled in 1933 by Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Franklin Roosevelt was far from a perfect president—or man—and made many serious mistakes. But most of his worst missteps took place in his second term of office, not his first. And certainly not in his first year. Seasoned with years of political experience, including governing what was then the most populous state in the nation—New York—he also had a team of loyal, able and focused aides.

In those long-ago days, the West Wing was managed by just four people, known as the White House Secretariat.

The Steve Bannon of FDR’s first term was Louis McHenry Howe. He was as fearsome-looking as Bannon, but had no other agenda than to get FDR into the White House in order to fulfill his destiny. He smoked like a chimney, cussed like a sailor and regularly handed out business cards that identified himself as “Colonel Louis Rasputin Voltaire Talleyrand Simon Legree Howe.”

His lieutenants were Steve Early and Marvin McIntyre. Early, a former Associated Press reporter, knew most of the correspondents in Washington and treated them with respect. He was known to have a short fuse, but made FDR available to the press twice a week and conducted his own briefings on other days. The correspondents were amazed that FDR accepted questions on the spot—rather than in writing, as previous presidents had—and were soon eating out of his hand.

McIntyre, also a former press member, was said by a contemporary observer to have the job of “keeping the schedule of appointments and stroking ruffled plumage,” as well as serving “as a psychological guinea-pig for the Rooseveltian political experiments” as a stand-in for “the average man in the street.” Neither Early nor McIntyre was said to have a political agenda other than that of “the Boss.”

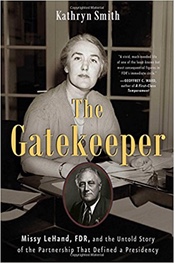

The final member of the secretariat was the most unusual in that she was a woman. Marguerite Alice “Missy” LeHand was the first female private secretary to an American president and reported directly to FDR rather through Louis Howe. Her office was the only one connected to FDR’s, and she handled his private and public affairs with tact and zealous discretion. Like Howe, she lived in the White House with the Roosevelt family. Like Howe, she was not afraid to speak truth to power.

What all four members of the secretariat shared was a long history with FDR—they had all been part of his 1920 campaign for vice president, and Howe had gotten on his band wagon a decade before that—and absolute, unquestioning loyalty. To this point, the killing hours—plus a lot of cigarettes—put them all into an early grave.

Louis went first, dying of heart and lung disease in 1936 after spending more than a year in an oxygen tent in the White House and a bed at the naval hospital. LeHand succeeded him as de facto chief of staff—again, a position that has never been held by a woman before or since—and was said to have the place running like a Swiss watch. It literally killed her. In 1941, at age 44, she suffered a stroke and had to retire. She died three years later. By then, McIntyre had succumbed to tuberculosis. Like Howe, he was 65 when he took his last labored breath.

The successor to LeHand and McIntyre was Edwin M. “Pa” Watson, originally the president’s senior military aide, who handled both the appointments and chief of staff duties from 1941 to 1945. He died at age 61 of a cerebral hemorrhage on the voyage home from the Yalta conference, followed a couple of months later by FDR, who suffered the same fate on April 12, 1945, age 63.

Of the original secretariat, only Steve Early survived his colleagues. He served the Truman administration in two different posts, and died at age 61 after suffering a heart attack while playing golf.

None of these people were extraordinarily gifted. None of the original secretariat had a college degree. What they shared, and what is sorely lacking in the White House today, is a large measure of loyalty and respect for their president, coupled with a genuine feeling of friendship for “the Boss.” None of them wrote a tell-all book about working with Roosevelt.

The loyalty ran both ways. Although he was a demanding boss, FDR genuinely cared about his White House “family.” He paid the medical bills of Howe, McIntyre and LeHand, left a generous bequest to LeHand in his will—though he outlived her—and to this day his family pays for the upkeep of her grave.

Hard to imagine anything of that nature happening today.