Should Smart Black Students Be Sent to Special Schools?

In the Lincoln Center Theater Review, a magazine for theatergoers at New York’s theater/music/dance/opera center, a writer describes the racial educational "pipeline" as a half-century old system in which talented minority high school students are placed into programs at special schools to enable them to get into good colleges and succeed in life. The writer explains that the other pipeline is the one that keeps minority students in failing inner city neighborhood schools, doomed to failure forever.

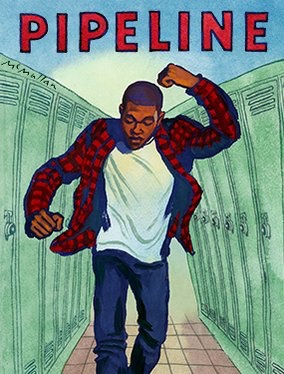

In Dominique Morisseau’s new play, Pipeline, that opened at Lincoln Center this past week, African-American teenager Omari is trapped in that pipeline. Pushed hard to do well by his teacher/mother, the teenaged student flies into a rage in the classroom, shoves his teacher and faces expulsion and perhaps criminal charges. Omari’s story is about the failure of the pipeline, but writer Morisseau never explains what the pipeline is, leaving the audience uncomfortably puzzled throughout most of the story.

The academic “pipeline” has been there since the integration of the nation’s public schools in the mid-1950s and for sixty some years has been problematic. Is it a good idea for bright, black teens to use the pipeline to get ahead or would they be just as successful if they stayed in their local academic institutions? There are two schools of thought on the issue, in both white and black communities, and both claim they are right. Both are represented in the play.

Although the concept of the pipeline is missing from the script, the audience figures it out. The school issue, though, is not the real strength of the play. The power of Morissean’s moving and well written story is the frustration of the teacher/mom and the friction in her family. She does all she can to get her son Omari, who at first seems a smart-ass teenager, to succeed, even getting down on her knees and begging him to unload his problems to her. Omari, like all teenagers in all generations, is in open rebellion against his mom. The third figure and a controversial one, is dad. He is a successful businessman, too busy for his ex-wife and child, and with a new girlfriend. There is a scorching scene in which a furious and shattered Omar confronts him and charges him with emotional neglect and being a dad who just does not care about his son. It is this trauma of the family, as well as the troubles with the educational pipeline, ever a source of controversy in America, that makes the drama as strong as it is.

And then there is Omari himself. I got a kick out of Omari. He is just a kid, a teenager trying to cope with life and, at the same time, his cantankerous girlfriend. He does not know what he wants in this world and certainly does not understand how the pipeline works. I know so many parents, of all faiths, ages, wealth and colors, who will do anything, absolutely anything, to make their kid a success. The kid? He/she does not care one bit. It is all an effort for mom and dad to bang his/her chest and tell their friends how smart their kid is, and, by inflection, how smart they are. My question: if all these parents and kids are so smart, why is this country such a mess?

Morisseau does a good job on that issue.

Her main point remains the subject of extensive national controversy. Are African American teenagers doomed to failure if they can’t use schooling to force their way out of inner city lives that may trap them as adults? Is all of life pre-ordained because of color?

The jury is still out on that argument, has been for sixty years, and will be out for a long, long time. Morisseau’s play is a good one, but has weaknesses. The start is way too slow. Sub plots are developed and then dropped. There is an intense scene in which a teacher has to break up a fist between two black teenagers. How does that end? You do not know.

Director Lileana Blain-Cruz did a fine job of letting her actors breath. They are not in a rush to tell the story. Under her guidance, they take their time. She allows the story to simmer and then explode at the end. She gets sterling performances from Karen PIttman as mom Nya, Tasha Lawrence as the other teacher, Laurie, Namir Smallwood as Omari, Heather Velazquez as his girlfriend, Jasmine, Morocco Omari as the dad and Jaime Lincoln Smith as Dun, who has to be the smartest security guard who ever lived. Together, this ensemble tells a story you read about in the news or see on television every day. It is the endless fight for success, and racial acknowledgement, in the United States.

The play is augmented by a harsh and gritty series of black and white video projections against the entire back wall of the theater of high school life, including fights, that are a real plus to the story.

Despite the aforementioned minor troubles of the play, Pipeline is a solid and impressive story about an ongoing dilemma in American society. Can you buy success for your children by putting them in special schools, or in pricey prep schools? Does an education equal success in America?

PRODUCTION: The play is produced by Lincoln Center. Sets: Matt Saunders, Costumes: Montana Levi Blanco, Lighting: Kyi Zhao, Sound: Justin Ellington, Projections: Hannah Wasileski. The play is directed by Lileana Blain-Cruz. The play runs through August 27.