Trump Is a Different Kind of Politician, but He’s Not THAT Different

Critics lament that our twenty-four-hour news cycle turned the 2016 election into a horse race or a sideshow, and they’re right. It was treated as a kind of sporting event. But democratic politicians have always had to lure in voters. In the early nineteenth century, southern backcountry voters came for the free food, the fistfights, and such rowdy forms of entertainment as the “gander pull.” In this indelicate contest, two men on horseback competed for the honor of yanking off the head of a goose. As in the “Squatter’s Tale” about “Old Sug,” men at the polls expected to get a serving of whiskey and brown sugar as they listened to longwinded speeches. It is in the nature of democratic politics for office seekers to appeal with little subtlety to the tastes of the electorate. In the early twentieth century, in his run for governor and the U.S. Senate, Jeff Davis of Arkansas gained the favor of his working-class audiences by ripping off his collar and rolling up his sleeves. He intentionally imitated the uncouth, ungrammatical speech of the lower classes. Even Lyndon Johnson had to canvass in Texas for his Senate seat with a traveling band. Governor “Big Jim” Folsom of Alabama strutted across the stage barefoot.

Trump’s antics

mirror this long tradition. One of his campaign managers, Paul

Manafort, admitted at one point that Trump was simply “projecting

an image.” Who’s surprised? Americans have a taste for a

“democracy of manners,” which is different from real democracy.

Voters accept huge disparities in wealth, while expecting their

elected leaders to appear to be no different from the rest of us. By

talking tough, by boasting that he’d love to throw a punch at a

protester, candidate Trump pretended he was stepping down from his

opulent Manhattan penthouse to commingle with the unwashed masses.

Wearing his not-so-classy bright red Bubba cap, and crooning at one

rally, “I love the poorly educated,” he built upon a recognizable

strain of American populism.

Trump’s antics

mirror this long tradition. One of his campaign managers, Paul

Manafort, admitted at one point that Trump was simply “projecting

an image.” Who’s surprised? Americans have a taste for a

“democracy of manners,” which is different from real democracy.

Voters accept huge disparities in wealth, while expecting their

elected leaders to appear to be no different from the rest of us. By

talking tough, by boasting that he’d love to throw a punch at a

protester, candidate Trump pretended he was stepping down from his

opulent Manhattan penthouse to commingle with the unwashed masses.

Wearing his not-so-classy bright red Bubba cap, and crooning at one

rally, “I love the poorly educated,” he built upon a recognizable

strain of American populism.

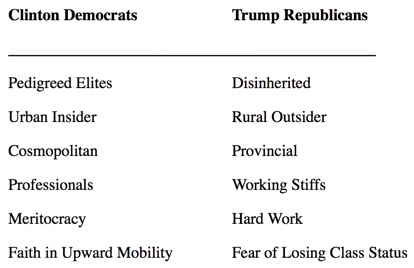

Presidential elections are battles over worldviews. The symbols that mattered most to Trump voters were about class, but the metaphoric meaning played out in a more expansive rhetoric that divided constituencies by competing markers of identity. The unspoken and spoken themes of the political contest were:

The election has opened up festering wounds. The deepest of these exposes how we measure the value of civic virtue and hard work. Many successful Americans believe they have made it on their own and have little patience for the complaints of those left behind. Trump perceived a world of winners and losers, and many of his supporters want to reinforce the old stigmas that separated the productive worker from the idle. They wanted the boundaries between the unemployed and employed to be firmly enforced, not weakened. “Make America Great Again” is another way of saying that hard work is no longer automatically rewarded as a virtue. It tapped the anxieties of all who resented government for handing over the country to supposedly less deserving classes: new immigrants, protesting African Americans, lazy welfare freeloaders, and Obamacare recipients asking for handouts. Angry Trump voters were convinced that these classes (the “takers”) were not playing by the rules (i.e., working their way up the ladder) and that government entitlement programs were allowing some to advance past more deserving (white, native-born) Americans. This was how many came to feel “disinherited.”