Impeachment Isn’t a Job Best Left to Professionals. It’s a Job for the Politicians.

House Speaker Paul Ryan surely spoke for the contemporary technocratic ethos when, asked about what was then the latest allegation about a Russian connection to the Trump campaign, he said the investigation ought to be left to “professionals” and committees. The reference was to investigations by Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller III on the one hand and by congressional panels on the other. That was half right. With allegations against Trump veering into the territory for which the power of impeachment exists, this is no job for professionals. It is precisely the kind of work that ought to be left to politicians.

That does not mean investigations

should not be conducted professionally. The point, rather, as the

Princeton University scholar Keith Whittington has explained,

is that Congress, an independent branch of government, ought not to

rely on an investigation conducted by the executive department. More

broadly, the point is this: Investigations should continue, but ample

information for assessing the essentially political question of

impeachment—from President Trump’s erratic response to the North

Korea crisis on the one hand to his apparently immovable support from

a third of the public on the other—already exists in the public

record.

That does not mean investigations

should not be conducted professionally. The point, rather, as the

Princeton University scholar Keith Whittington has explained,

is that Congress, an independent branch of government, ought not to

rely on an investigation conducted by the executive department. More

broadly, the point is this: Investigations should continue, but ample

information for assessing the essentially political question of

impeachment—from President Trump’s erratic response to the North

Korea crisis on the one hand to his apparently immovable support from

a third of the public on the other—already exists in the public

record.

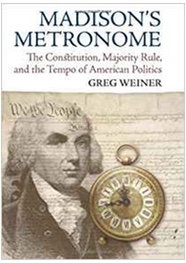

During the Constitutional Convention of 1787, James Madison described the power of impeachment as a cure for presidential “incapacity, negligence or perfidy. … He might lose his capacity after his appointment. He might pervert his administration into a scheme of peculation or oppression. He might betray his trust to foreign powers.”

It is worth observing that these are all offenses, but only one of them—peculation, which is to say feeding at the public trough—is likely to be provable as a technical crime. The rest occupy the hazy category for which Federalist 65 said impeachment was created:

The subjects of its jurisdiction are those offences which proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust. They are of a nature which may with peculiar propriety be denominated political, as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself.

Impeachment thus differs fundamentally from the prosecution of statutory crime. Its procedural trappings—the outward equivalent of indictment by the House and jury trial by the Senate—encourage us to think of it technically. So does the phrase “high crimes and misdemeanors.”

Yet the phrase itself is a technical one. “High misdemeanors” appears in the writings of the British legal commentator William Blackstone, who was revered in early America, as an offense against society: “the mal-administration of such high officers, as are in public trust and employment.”

That is, in fact, how it got into the Constitution. George Mason of Virginia, a delegate to the Convention, felt an early draft of the Constitution was too specific in confining causes of impeachment to “treason” and “bribery,” so he proposed adding “maladministration.” That did not mean simply incompetence. The prefix “mal” implied ill intent—again, not a crime, but still an offense. Madison objected that the term was too vague, so Mason substituted “high crimes and misdemeanors.”

The phrase denotes a category of political offenses committed against the society. Its purpose is not to punish a past offense but rather to protect society against future ones. The great jurist and constitutional commentator Joseph Story thus wrote in 1833 that these offenses encompassed crimes but were not limited to them. Rather, they included “political offences, growing out of personal misconduct, or gross neglect, or usurpation, or habitual disregard of the public interests, in the discharge of the duties of public office.” Crucially for Story, only statesmen, as opposed to judges, had the breadth of experience and perspective to weigh the inculpatory and extenuating circumstances that produced the acts.

So it is with lawmakers today. They are already amply aware of allegations that President Trump winks at white supremacists, responds erratically to crises and plays loosely with the truth. They are equally aware of the defenses against these charges, of the difficulties of confronting crises, and of the impossibility of politicians, like spouses, speaking literal truth at all times. They are not yet, to be sure, aware of the extent, if any, of the Trump campaign’s connections with Russia. The results of these investigations—which they should pursue themselves, even as they evaluate the results of Mueller’s work—can guide them as well.

In these senses, impeachment is an inescapably political process. But that is true in another sense too. It demands prudential judgment and public accountability. That polls indicate a third of the country is resolutely committed to the Trump presidency—and that a considerable proportion of this number sees his Administration pitted against an entrenched establishment they are increasingly convinced is out to destroy him—is cause for grave caution in a process that would demand it even had his support totally collapsed.

To say impeachment is political is not to say it is a tool for relitigating elections, even were there clear evidence of buyer’s remorse. It is, rather, to characterize the range of offenses and the disposition with which they should be addressed. To say the device is forward-looking—that is, that its purpose is protective rather than punitive—is not to say lawmakers can impeach purely on the basis of an anticipated future offense. It requires a past one—almost certainly a clear pattern of them—as a basis for assessing the likelihood of future transgressions.

But the public record is already ample on many of these scores. The investigatory record is filling. Prudential judgments await. This, as much as any other task they will undertake in office, is a job for the politicians.