How Fake News Becomes History

In the past year, commentators and scholars have devoted a great deal of attention to the phenomenon we now call “fake news,” the spreading of false narratives through social networks. In spite of all the resources we now have at our disposal to fact check suspicious stories, large numbers of people continue to believe in spectacular conspiracies.

Some fake news is so outrageous it is

incredible that anyone would believe it. There was, for example, the

fable dubbed “Pizzagate,” which said presidential candidate

Hillary Clinton was running a pedophile ring out of a Washington D.C.

pizzeria. In fact, the Pizzagate story gained more traction, and was

shared more often via social media, than other false stories that

seem at least somewhat possible, for example, the story that someone

at Google was tinkering with the search algorithms to benefit

Clinton.

Some fake news is so outrageous it is

incredible that anyone would believe it. There was, for example, the

fable dubbed “Pizzagate,” which said presidential candidate

Hillary Clinton was running a pedophile ring out of a Washington D.C.

pizzeria. In fact, the Pizzagate story gained more traction, and was

shared more often via social media, than other false stories that

seem at least somewhat possible, for example, the story that someone

at Google was tinkering with the search algorithms to benefit

Clinton.

When journalist Craig Silverman of BuzzFeed News made a detailed study of “fake news” he found that the more incredible a story was, the more likely it was to be shared. The stories worked because, he told NPR, what “these pages are very good at is they bring in emotion into it, anger or hate or surprise or, you know, joy. And so if you combine information that aligns with their beliefs, if you can make it something that strikes an emotion in them, then that gets them to react.”

A story about Google algorithms aligns with an existing belief about the candidate Donald Trump branded “Crooked Hillary,” but it does not take it to the next level the way a pizza parlor pedophile ring does.

When Oscar Wilde was arrested for “gross indecency” the sensational trial created a narrative about the playwright. He became, in the public imagination, a Svengali, a vile corrupter of young men. It would fall to his friend and later literary executor Robert Ross to try to change that narrative.

He did this, in part, in the way you might expect. He worked to release Wilde's Complete Works and put the focus back on his artistry, not his personal life. He also released a judiciously edited version of a long essay Wilde had written in prison in the form of a letter to his lover Lord Alfred Douglas. The Ross version of De Profundis presented its writer as a reformed genius who had discovered in the figure of Christ the Artist the value of humility. It was a sensation and caused many people to reevaluate Wilde's body of work.

Yet Ross was also circulated some colorful stories that seem to do nothing to improve Wilde's public image. He told the journalist Frank Harris, who was writing a biography of Wilde, some tall tales about Wilde's death. One was that Wilde's body “exploded” in a spectacular and disgusting fashion. The second was that years later, when the body was exhumed to be moved from a pauper's grave to its current resting place at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, Wilde's body had been preserved, and Ross went down into the grave, and moved it with his own hands. Even if Wilde's body (after exploding) had been preserved to the extent that Ross would want to touch it, the idea that he could have lifted it out of a grave with his bare hands is far-fetched given the relative sizes of the two men.

Reginald Turner, who was also with Wilde when he died, denied the exploding body story. Yet the very outrageousness of the macabre tale persuaded Wilde's biographer Richard Ellmann that it must have been true. He reasoned that Ross would have no reason to invent something so disgusting and Turner might have wanted to conceal it out of respect for the dead.

Indeed, why would Ross tell a tale that is so unflattering to Wilde? To answer this you need to shift perspective and think of it not as a story about Oscar Wilde, but as a story about Robert Ross. In telling a detailed, exaggerated, fabricated story about the horrible things he had to deal with, he advanced a narrative about his own dedication to his mentor. Ross was a man so devoted to Wilde that he would help clean up the liquids that were released from his dying body, and would move that body from one grave to another with his own hands.

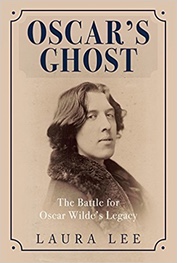

In the course of my research for Oscar's Ghost, I found that in the years immediately following Wilde's death it was common to blame his downfall on his admirers—in the plural—who pushed him to extremes of behavior, and encouraged him in his ultimately disastrous lawsuit against the Marquess of Queensberry. There is every reason to believe that the people who made these accusations counted Ross among those admirers. Ross was highly effective in changing that narrative. No one speaks any more of Wilde being pushed to extremes by his admirers. Only one admirer, Lord Alfred Douglas, is now considered responsible.

At the time Ross was talking to Harris about corpses and graves, he was also leaking letters and unpublished parts of De Profundis and advancing the idea that Douglas had benefited from his association with Wilde at the height of his fame, that he singlehandedly led him to a foolish battle, and that he abandoned him when the money ran out. While Douglas was happy to share in Wilde's joy, it was Ross (as the death stories illustrate) who was there to deal with all of the unpleasant fallout.

Ross could have stuck closer to the truth and talked about all of the work he did on Wilde's estate, the business deals he negotiated, while Douglas was working on his poetry, dining with his fellow aristocrats and going off on hunting holidays. But that did not have the same visceral impact.

Over the years Ross's stories about what happened to Wilde's body have not been a major feature of the Wilde mythology. Yet the underlying moral of them has been. Robert Ross was the faithful friend who advised Wilde to do the right thing while Douglas was a chaotic force who drove him to do the wrong.

The lesson of this history is that the real problem with fake news is not that people continue to believe nonsense like Pizzagate (although apparently a surprising number of people do), it is that the outrageous story emotionally supports an existing concept and colors the way more factual stories are interpreted. The pizza story will never make it into the history books, but the fact that people saw Hillary Clinton as “crooked” will. That is how fake news becomes history.