Trump’s New Communications Director Reminds this Historian of Missy LeHand

Hope Hicks was just named communications director at the White House, the third person to hold the job since the Trump administration began in January. At age 28, she is also the youngest communications director in White House history.

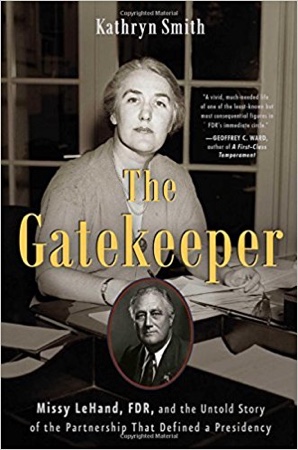

Hicks is sometimes described as Trump’s gatekeeper. The same word was used to describe another female White House aide who, more than 80 years ago, served President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. There are striking similarities between Hope Charlotte Hicks and Marguerite Alice LeHand.

LeHand joined the staff of FDR’s ill-fated campaign for vice president in 1920, and then became his private secretary when he began working at a Wall Street law firm the next year. She was 23 years old. The Roosevelt children dubbed her “Missy,” and soon everyone used the name. (Trump’s nicknames for his aide are “Hopie” and “Hopester.”)

Hicks, who was hired as Trump’s campaign press secretary in January 2015, is described as one of his longest serving aides. (She had previously worked for the Trump Organization.) Missy served FDR for almost 21 years. It’s all relative, however. In Trump’s world, 21 months is a very long time.

LeHand was FDR’s confidante, companion, advisor, and friend. (There has been speculation they were lovers as well, though there is no proof of this.) Wrote journalist John Gunther, “Between Roosevelt and Missy the closest possible rapport existed; they were as sensitive to one another as brother and sister.”

Likewise, Vogue recently reported about Hicks, “She is roundly characterized as a veritable Trump whisperer (she reportedly knows not to disturb him when he’s watching golf), a confidante and right-hand woman who ‘totally understands’ him, and a loyalist who has earned his complete trust, which he appears to dole out with the intensity of a mob boss.”

Hicks is one of the highest paid people on the White House staff, earning $179,700. How times change. Missy topped out at a salary of $5,000 in 1941, which is about $83,500 in current dollars. It was a good salary in the Depression—but it was half what her male counterparts earned.

There are other similarities. LeHand had the only office adjoining the Oval Office and used it as a back-door entrance for people FDR didn’t want on his official calendar, as well as people she wanted FDR to see. Hicks has had a desk outside the Oval Office since January, as befitted her media gatekeeper function, but has been known to give visiting journalists surprise access to her boss. Both have lived in the same building as the boss, Hicks occupying a free apartment in Trump Tower since she joined his presidential campaign; LeHand lived in a free suite in the White House on the floor above the Roosevelts.

They seem to share the same discretion. Hicks is low key, reticent, and doesn’t appear on cable television shows. Her clothing is understated and elegant. She seems to spend more time with Trump than any other aide, other than his daughter Ivanka and son-in-law Jared Kushner. Missy was famously reticent and ever-present as well, and was named one of the best-dressed women in Washington for her “up-to-the-minute style … combined with businesslike appearance.”

The extent of Hicks’s power is unknown, but if she retains Trump’s trust, it is likely to grow.

LeHand’s life offers both a road map and a warning. A single woman whose only serious romantic relationship was with a U.S. ambassador who served in Europe, she devoted her days and many of her evenings to the president, including traveling with him on weekends when he left the White House. Her level-headed advice and shrewd judgement helped mold policy and select crucial appointees. She suggested his first attorney general and advised him on Supreme Court nominations.

Eventually, she assumed most of the functions of a White House chief of staff, though the title was not used until Eisenhower’s day. Her power was so great that the president could not be woken after he went to bed without her permission, such as when the call came in on September 1, 1939 announcing that Hitler had invaded Poland.

LeHand was respected as one of the most powerful women in Washington—but it came at a high personal cost. At a White House dinner party in 1941, she fainted, setting off a chain of medical catastrophes that concluded with a major stroke. Partly paralyzed and with limited speech, she was forced to retire and died three years later at age 47.

After she left the White House, FDR called and wrote, but he never saw her again. His words, “She was utterly selfless in her devotion to duty,” are inscribed on her gravestone.