Five Forgotten Reforms Liberals Should Back

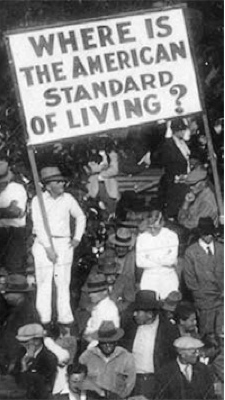

Progressives today are rightly focused on combatting the authoritarian Trump Administration. Trump’s encouragement of white supremacists and neo-Nazis, his misogynistic and racist policies, and his attempts to shred social programs and environmental protections are opposed by a decisive majority of the U.S. public. In earlier periods of U.S. history, progressive forces have been most effective in inflicting defeats on reactionaries when they coupled their resistance with a positive program that met the needs of millions of working people. Some of these campaigns achieved signal victories. Others fell short but are worth remembering today when many millions are mobilizing to defeat the right and looking to construct a better country out of the ashes of the Trump era.

The

achievements resulting from the struggles of the 1930s and1960s and

early 1970s are well known. Legislative victories included the Social

Security and Wagner acts (1935); Fair Labor Standards Act

(1938); Civil Rights Act of 1964; the Voting Rights Act and Medicare

(1965); Clean Air and Occupational and Safety acts (1970); Title IX

and the Clean Water Act (1972); and Women’s Educational Equity Act

and Equal Credit Opportunity Act (1974). Union membership rose

dramatically in the 1930s and 1940s and political representation by

women and minorities expanded in the wake of the egalitarian

struggles of the 1960s and 1970s. There were important legal advances

in dismantling legal segregation, advancing the principle of one

person, one vote, providing the right to birth control, including

abortion, and guaranteeing equal rights to women and minorities. The

conservative offensive that began around 1978 and has persisted until

today has led to a loss of the gains in unionization, weakening of

the Voting Rights Act, and limitations on abortion rights, among

other setbacks. Nevertheless, beachheads such as Social Security and

Medicare have been held to date and even strengthened.

The

achievements resulting from the struggles of the 1930s and1960s and

early 1970s are well known. Legislative victories included the Social

Security and Wagner acts (1935); Fair Labor Standards Act

(1938); Civil Rights Act of 1964; the Voting Rights Act and Medicare

(1965); Clean Air and Occupational and Safety acts (1970); Title IX

and the Clean Water Act (1972); and Women’s Educational Equity Act

and Equal Credit Opportunity Act (1974). Union membership rose

dramatically in the 1930s and 1940s and political representation by

women and minorities expanded in the wake of the egalitarian

struggles of the 1960s and 1970s. There were important legal advances

in dismantling legal segregation, advancing the principle of one

person, one vote, providing the right to birth control, including

abortion, and guaranteeing equal rights to women and minorities. The

conservative offensive that began around 1978 and has persisted until

today has led to a loss of the gains in unionization, weakening of

the Voting Rights Act, and limitations on abortion rights, among

other setbacks. Nevertheless, beachheads such as Social Security and

Medicare have been held to date and even strengthened.

Given the diversity and complexity of the country and the many challenges we have faced over the last several decades, the question of where progressives go from here to create positive change is not easily answered. A part of the answer may lie in an examination of some important but forgotten efforts of the Franklin Roosevelt era and the era of the 1970s and later years that fell short, as they may provide models for present-day struggles. Among these earlier campaigns are the 1932-1933 Black 30-Hour-Week Bill; the 1934-35 Lundeen Workers’ Unemployment, Old Age, & Social Insurance Bill; the Comprehensive Child Development Bill of 1971; the campaigns in 1945 and the 1970s for full employment legislation that would guarantee a right to a job for all; and the campaigns in the 1970s, 1990s, and the 2000s to strengthen the right of workers to unionize.

In the early 1930s, the U.S. faced its deepest crisis since the Civil War with millions of people destitute and thousands facing starvation, particularly in minority communities. It was a time of elite repression of working people and minority communities. Tens of thousands of Mexicans, including many who were U.S. citizens, were denied relief benefits and many were forcibly repatriated. African-American workers on Southern railroads were murdered by white supremacists who wanted their jobs. Lynchings were again on the rise after a decline in the 1920s. However, minority workers fought back against the repression and went on strike both by themselves in the fields of California, Texas, and Alabama and alongside non-minority workers elsewhere. Many workers joined unions and left-wing movements and organizations.

Labor unions and left-wing groups initiated two important legislative campaigns.

In the opening days of the Roosevelt Administration, the leadership of the American Federation of Labor sought to address the problem of unemployment by reducing the weekly hours of work from 40 to 30 without reduction in pay. The 30-Hour Bill sponsored by Senator Hugo Black, later Justice of the Supreme Court, (D-Alabama), had wide support from labor and liberal groups. Although it passed the Senate by a 53 to 30 vote, the House of Representatives failed to vote on it. Efforts to reduce the hours of work have occasionally erupted in subsequent decades but have not been sustained. U.S. workers tend to work long hours and have little paid vacation, sick, maternity, or holiday leave. A campaign to reduce the workweek and to increase paid vacation and other paid leave time, if successful, would expand employment and lead to a healthier and more contented work force.

Another early Great Depression campaign that spread throughout the country was that of grass roots movements for unions and for relief, jobs, and unemployment insurance. Hundreds of organizations with millions of members campaigned for the Lundeen Bill. Minnesota Farmer Labor Representative Ernest Lundeen’s bill proposed a comprehensive social insurance system “for all workers, including all wage earners, all salaried workers, farmers, professional workers and the self-employed.” The bill provided for compensation equal to average earnings for wages lost due to layoffs, injuries, illnesses, maternity, and old age. Mothers of children under eighteen also would receive allowances if they lacked male support. The proposal included a provision against race, sex, and age discrimination, leading historian Alice Kessler-Harris to comment that the bill, “threatened to override gender and racial proscription by defining work capaciously enough to include virtually everyone.” Financing the universal and egalitarian system envisioned in the Lundeen bill would have come from general tax revenues.

The Lundeen Bill was reported out of the House Labor Committee in 1935, but Congress failed to enact it. Instead, the Congress passed and President Roosevelt signed the more limited Social Security Act, which initially excluded many workers, especially women and minorities, from its coverage and provided separate systems for those covered by employment and those covered due to specific needs. Considering the fact that the U.S. had no social insurance system, the Social Security Act represented a meaningful advance and, in many respects, has been improved. Unfortunately, the Social Security Act’s initial division between needs-based and employment-based benefits has persisted and led to the weakening of needs-based benefits over time. Moreover, the unemployment compensation system enacted as part of the Social Security Act has numerous restrictions and provides no benefits to the long-term unemployed and those not seeking work. Currently, one quarter of those counted in official unemployment statistics receive benefits. Returning to the vision of the Lundeen Bill, that all of us are entitled to a decent standard of living, would provide grass roots movements today with a comprehensive program to make the United States a healthier and happier place.

The struggles of the 1960s and early 1970s led to important civil rights, feminist, labor, and environmental advances. One vital reform that failed of enactment was a national child-care program. Critical players in developing and supporting the Comprehensive Child Development Act were the AFL-CIO and women's, child advocacy, and welfare rights groups. The measure passed the Congress in 1971 but was vetoed by President Richard Nixon. The failure to enact a national high-standards, well-funded professional child care program has kept the child care industry a low-wage arena and left most working parents to struggle with haphazard, inadequate, or bad care. Placing this legislation back on the national agenda would give working families hope for improving the quality of their lives.

Perhaps of greatest significance are the campaigns in 1945 and the 1970s for the federal government to plan a full employment economy and to guarantee everyone a right to a job. The first effort emerged out of the experience of the Great Depression and World War II. The campaign stemmed from both a fear of a return to depression conditions after the war and an optimistic view of the federal government’s role since it had created a near full employment economy during the war. In his January 1944 State of the Union address, President Franklin Roosevelt had called for the enactment of an Economic Bill of Rights to include the “right to a useful and remunerative job in the industries or shops or farms or mines of the Nation,” and “the right to earn enough to provide adequate food and clothing and recreation.” The Full Employment Bill of 1945 would have mandated that the federal government plan its budget to produce a full employment economy so that all could exercise their right to full-time work and living standards could rise. Labor, farm, liberal, social welfare, and religious groups supported the legislation. The bill passed the Senate on a 71-10 vote but failed to pass the House of Representatives. The Congress passed and President Truman signed the more limited Employment Act of 1946, which set a goal of creating “maximum” employment.

Another attempt to pass full employment legislation took place in the wake of the deep 1973-1975 recession. The Equal Opportunity and Full Employment Bill of 1974 would have led to federal planning of jobs for all, including those not currently in the labor force. The bill would have created Job Guarantee Offices and neighborhood planning boards in communities across the country, a Standby Job Corps for those needing a temporary job, and a legal right to a job. Like the 1945 legislation, the 1974 bill envisioned jobs at decent wages. A much weakened version of the 1974 bill was enacted in 1978, the Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act. The law had no focus on good-paying jobs and dropped the innovative measures of the 1974 bill. Its one positive feature was to set a target of 4 percent unemployment in five years. Even this modest mandate was violated by Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan and has been ignored by subsequent administrations. Jobs created since the conservative offensive of the late 1970s have been high paying for a few and low paying for the many.

The Occupy Wall Street movement and Senator Bernie Sanders’s presidential campaign effectively highlighted the dramatic growth of inequality resulting from economic policies of the past forty years. Although many commentators assert that the U.S. today is at full employment, the National Jobs for All Coalition counts 18.2 million unemployed and underemployed, which corresponds to 10.9 percent of the labor force. In addition to the 7.1 million counted in official statistics as unemployed because they are actively seeking jobs, 5.8 million are discouraged workers who have stopped looking for work and 5.3 million are part-time workers unable to find full-time work. Moreover, the official unemployment rate among African-American teens is 23.4 percent. Returning to the full employment vision of the 1940s and 1970s campaigns means valuing the potential and dignity of every individual.

Essential to any effort to make the U.S. more democratic is to regain the right to unionize. In the 1930s and 1940s, the grass roots unionization struggles combined with the support of the National Labor Relations Board authorized by the 1935 Wagner Act led to a significant growth of unionism. Restrictions on unions enacted in the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 and aggressive anti-labor campaigns by corporations have brought about a dramatic decline in unionization. The one bright spot for unions in recent decades has been the growth of public sector unionization, but the rights of public sector unions since 2010 are being challenged by state-level legislation. The unionization rate in 2016 was 10.7 percent among all workers and 6.4 percent among private-sector workers. The latter rate was significantly below the comparable pre-New Deal figure.

Efforts by unions and their allies to make it easier for workers to join unions have taken place on three occasions since 1976. The Labor Law Reform Bill of 1978, which would have increased sanctions against labor law violators and speeded up NLRB elections, passed the House of Representatives by a wide margin but fell two votes short of the sixty needed to end a Senate filibuster. In the 1990s, the Workplace Fairness Bill to end employer replacement of striking workers passed the House of Representatives twice; efforts to end Senate filibusters failed by three votes in 1992 and seven votes in 1994. In 2007 the Employee Free Choice Bill to provide a card check process for workers to unionize passed the House but fell nine votes short of ending a Senate filibuster. Efforts to secure a vote on the bill during President Barack Obama’s first term did not come to fruition. Although overcoming determined business and conservative opposition to pro-union legislation is an uphill battle, there is no more important democratic reform than giving workers a say in their workplaces. Perhaps what we need is a law that mandates a vote each year in every non-union workplace on whether workers want to join a union. Call it the U.S. Workplace Democracy Act.

Grass roots mobilizations are taking place today to defeat right-wing initiatives to dismantle voting rights, freedom of expression, public education, and other features of our democracy. There also are growing movements to protect the undocumented and provide for a path to citizenship, and to enact a single payer national health care program or Medicare for All.

Progressives may wish to focus on these five forgotten reform measures important to improving the lives of working people and all who are hurt by the domination of the country by the 1 percent:

1. reduce the work week to 30 hours and expand paid leave;

2. provide guaranteed jobs at a living wage to all;

3. provide a decent standard of living to everyone;

4. establish a national child care program; and

5. reestablish the right of all workers to join unions.

We should tap the accumulated wealth of the United States to make the U.S. a more just society.