What Ken Burns and Lynn Novick Want Us to Believe Is that Americans Were Innocents in Vietnam

Click HERE for HNN's Complete Coverage of "The Vietnam War" By Ken Burns & Lynn Novick

The documentary film of the Vietnam War by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick and airing on public television makes for fascinating viewing. The documentary concentrates primarily upon the stories of American veterans of the conflict who relate their experiences with considerable candor. These accounts are supplemented by incredible footage of the war, and a sense of balance is also provided through the stories of soldiers from both North and South Vietnam along with accounts of American antiwar activists. Although attention is given to atrocities committed by both sides in the conflict, including the My Lai massacre perpetuated by American forces, Burns and Novick are sympathetic in the treatment of their eyewitnesses. Criticism is generally reserved for the leaders, such as Presidents Dwight Eisenhower, John Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, and Richard Nixon along with Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, and General William Westmoreland, who made the decisions to place these young men in harm’s way.

Nevertheless, Burns and Novick somewhat let these decision makers off the hook by suggesting that the road to hell in Vietnam was paved with good intentions. Burns and Novick perpetuate the belief in American innocence by arguing that misguided policies in Vietnam were based on a sincere desire to protect the people of Southeast Asia from the evils of international communism. Thus, the divisions in American society fostered by the Vietnam War may be reconciled through the fact that we were trying to do the right thing. Yet, this faith in American innocence ignores the history of national expansion well before the onset of the Cold War and the perception of communism as a threat to the American way of life.

In fact, expansionism or imperialism, often obscured in a cloak of innocence, has been at the heart of the American experience. The nation was founded on the concept of manifest destiny. The English settlers such as the Puritans were on an errand into the wilderness of North America to establish a civilization that would be a shining example to the world. One of the problems with implementing this divine mission was that the land chosen for settlement was already occupied by Native people. Progress would require the subjugation of these people who would have to be killed, removed, or converted to Christianity. Native resistance to the expansion of innocent settlers seeking to improve the lot of their families and bring civilization to the wilderness was considered barbaric.

For example, Thomas Jefferson, in the Declaration of Independence, accused George III of endeavoring “to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions.” This attitude toward the Native population of North America continued to reflect American opinion as the new nation crossed the Appalachian Mountain and Mississippi River into the American West. Progress was blocked by Indian massacres, so the Native population was placed on reservations under the supervision of the American military. This policy certainly found parallels in the Strategic Hamlet policy pursued by the United States in Vietnam, and those who remained outside of the American hamlets in South Vietnam were viewed as hostiles or Viet Cong. American continental expansion was also encouraged by a desire for greater slave territory and an aggressive war against Mexico which allowed the United States to obtain California and the American Southwest.

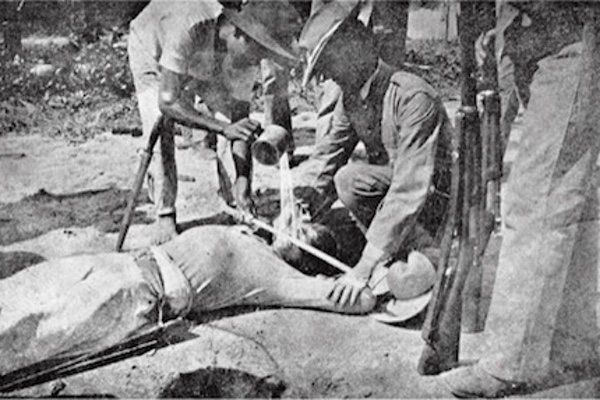

American expansionism did not stop at the ocean’s edge, and a desire for additional markets led business interests to promote expansionism into the markets of the Caribbean, South America, and Asia. The culmination of these efforts was the Spanish-American War of 1898 in which the United States acquired Puerto Rico, Guam, and Philippines in addition to a virtual protectorate over Cuba. The acquisition of the Philippines also paved the way for the annexation of Hawaii. The United States was now a full-fledged imperial power. Americans, nevertheless, still perceived themselves as, according to Mark Twain, “innocents abroad,” who sought to bestow the benefits of their superior civilization upon the people of the Philippines. The Filipinos, however, saw it differently and resisted American annexation as an affront to their desire for self-determination. In the ensuing conflict, resistance to American annexation was brutally crushed by employing such tactics as torture and waterboarding, forcing civilian populations into concentration camps, destroying crops and villages in order to deny rebels a food supply, and operating search-and-destroy missions that found it difficult to distinguish between peaceful villagers and rebel soldiers. In the Philippine-American War (1899-1902), 4,234 American soldiers were killed with another 2,818 wounded. Filipino deaths as a result of the war are estimated to exceed a quarter of a million people. The American experience and tactics in the Philippines from 1899 to 1902 were repeated in Vietnam although this war was not considered by the Burns and Novick film, undermining the filmmakers’ perception of American innocence.

Thus, the history of American territorial expansion and imperialism is a theme overlooked by the Burns and Novick documentary. In the post-World War II world, American global interests were addressed by the Truman Doctrine in which the United States promised military support to regimes resisting communist aggression. This policy, unfortunately, led to American support for dictatorships and authoritarian governments around the globe in nations such as Nicaragua, the Philippines, Iran, Iraq, Indonesia, Brazil, Argentina, Greece, South Africa, and South Vietnam. Burns and Novick document the corruption and anti-democratic facets of the Saigon regime in South Vietnam, but they neglect to chronicle how American policy in Vietnam fit into a larger program of support for authoritarian regimes during the Cold War.

In conclusion, Burns and Novick shed light upon the American experience in Vietnam with their detailed stories of American and Vietnamese combatants, but in their desire to bring some comfort and closure to the divisions exacerbated by the conflict, they tend to ignore the larger truths of American imperialism by perpetuating the myth of American innocence—a line of analysis that was maintained by many academics in the antiwar movement. These are difficult concepts for many Americans to confront, but if we really want to learn from the Vietnam experience, we need to deal with these issues of innocence, expansion, and imperialism.