About Those Media Mega-Mergers: Let’s Hope They Don’t Go Through

The recent rush toward media consolidation—AT&T’s $85.4 billion bid to acquire Time Warner and Disney’s $52.4 billion offer for key parts of the 21st Century Fox empire, including the movie and TV studios—prompts the question: what’s at stake and why should we care? Aren’t these just corporate shuffles that might bounce a few high-ranking executives out of their jobs, but result in lower overhead, greater efficiency, and, ultimately, improved products and services to the customer? While that might be what the promoters of these prospective mergers would like us to believe, history urges caution. Past experience shows that media ownership determines whose voices get heard, what kind of innovation occurs and at what pace, and who gets to profit from content creation and dissemination. Concentrated control tends to reduce all of the above, impacting the free flow of ideas so vital to the health of democracy.

Consider

the example of the U.S. motion picture industry, the mainstay of

popular culture production, which ever since its inception has tilted

toward consolidation with a covetous eye toward monopolization and

vertical integration. The reasons are simple. Movies are very

expensive to make, ever increasingly so, and public taste so

difficult to predict. A few big flops can drive a company onto the

ropes financially. Competition exacerbates the risk: all that

annoying cross-bidding for talent (often resulting in astronomical

salaries that everyone except the recipients resents), all that money

thrown toward advertising in order to shout more loudly than one’s

rivals, and all that flashy, wasteful, image-boosting spending.

Wouldn’t it be nice, producers have always thought, to be able to

tell the talent what the shrewd business mind determines that they

are worth, and then to present one’s wares to the general public in

the same fashion that Henry Ford did when he said that his customers

could have a Model T in “any color so long as it is black”?

Consider

the example of the U.S. motion picture industry, the mainstay of

popular culture production, which ever since its inception has tilted

toward consolidation with a covetous eye toward monopolization and

vertical integration. The reasons are simple. Movies are very

expensive to make, ever increasingly so, and public taste so

difficult to predict. A few big flops can drive a company onto the

ropes financially. Competition exacerbates the risk: all that

annoying cross-bidding for talent (often resulting in astronomical

salaries that everyone except the recipients resents), all that money

thrown toward advertising in order to shout more loudly than one’s

rivals, and all that flashy, wasteful, image-boosting spending.

Wouldn’t it be nice, producers have always thought, to be able to

tell the talent what the shrewd business mind determines that they

are worth, and then to present one’s wares to the general public in

the same fashion that Henry Ford did when he said that his customers

could have a Model T in “any color so long as it is black”?

This desire is essentially the motivation behind the current proposed mega mergers. AT&T, now a service and equipment company—one of the nation’s largest internet and telephone providers and, through its ownership of DirecTV, the largest TV distributor —would gain control of content via Time Warner’s array of top drawer production companies: HBO, the Warner Bros. studio, and Turner Broadcasting, home of CNN and TNT. AT&T claims that it needs content in order to compete effectively against Comcast, which owns NBCUniversal, and Verizon, which owns AOL. Disney aims to extend its reach in content production by co-opting powerful rival Fox. Disney Chairman and CEO Robert Iger says the merger would improve story-telling, increase entertainment diversity, and enhance offerings to the consumer.

Such promises have not worked out well in the past. Perhaps most instructive, because it came the closest to succeeding in the extreme, is the example of the Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC), formed in 1908 and based on a pool of motion picture camera and projector patents held by the Edison Company and Biograph. The MPPC licensed only ten companies to make movies; anyone else who made a movie was deemed to be doing so illegally, subject to litigation or worse (reportedly, MPPC employees with guns and phony badges busted up unauthorized movie sets). To suppress costs, the ten MPPC-member producers agreed among themselves to pay no more than $60 weekly for performers, $50 weekly for directors, and $25 per film script, and they colluded to rent their movies to distributors and exhibitors at a uniform price.

By eliminating “destructive” competition, the MPPC producers claimed, they would be able to work together harmoniously to improve the art of motion pictures. In practice, they became lazy and greedy. They had no incentive to innovate: to do that would have exposed them to greater risk for little potential advantage. Bad acting, nonsensical plots, and sloppy camera work abounded in their output. Furthermore, because the MPPC producers had a sewn-up market—their licensed distributors and exhibitors were prohibited from using “illegal” independent movies—they stopped caring about the physical condition of their merchandise. Theater owners, many of whom were small time immigrant operators pursuing entrepreneurial dreams, reported receiving film with no sprocket holes or films that were in a state of putrefaction.

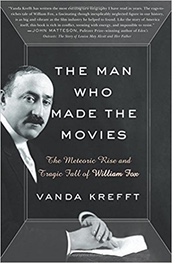

Its arrogance at controlling production soon led the MPPC to try to monopolize motion picture distribution—and it very nearly succeeded, putting out of business 119 of 120 companies nationwide. Everyone expected that the MPPC would next move to take over all U.S. movie theaters. It might well have … except for the 120th distributor, future Fox Film founder William Fox, who didn’t want to sell his small New York based business. Threatened with groundless license cancellation, Fox instigated the Department of Justice’s 1912 antitrust lawsuit against the MPPC. Three years later, a federal judge ruled that the MPPC was an illegal monopoly and ordered it dismantled. That landmark decision opened the industry to anyone who wanted to make movies and laid the foundation for the vibrant Hollywood studio system.

Only a few years later, though, another push began toward concentrated control. Adolph Zukor, having created industry giant Famous Players-Lasky (later Paramount) through a merger, began to swallow up smaller production and distribution companies, and used his dominant power to impose onerous conditions on theater owners. In response, leading theater owners formed First National to buy or make their own movies through independent production companies. In turn, Zukor launched a rapacious theater-buying spree and cracked down hard on small-time owners who resisted selling to him. With many of the nation’s first run theaters soon tied up by First National or Famous Players-Lasky, smaller movie producers were pushed downward. Fox Film, for instance, had made lavish spectacles during the mid-1910s, but dropped into the industry’s second tier in the early 1920s because it could now book most of its movies only into smaller, neighborhood theaters.

Zukor’s ambitions were stemmed by a 1921 Federal Trade Commission lawsuit that lasted several years and cost his company hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees. That pushback, combined with the propulsive prosperity of the late 1920s, led to an explosion of rivalrous creativity, with studios turning out movies like Wings, The Jazz Singer, 7th Heaven, Sunrise, The Crowd, and London After Midnight to name only a few highlights, and launching the talking pictures revolution (which Zukor believed was completely unnecessary) as well as introducing widescreen projection.

Ever fearful, the industry continued to pull toward consolidation. Warner Bros. and Universal started to amass theaters, Warners entered talks to merge with Paramount, and William Fox, once the industry’s loudest voice for open competition, landed the biggest deal in motion picture history in early 1929 when he bought a controlling block of stock in Loew’s Inc., parent company of MGM. That deal was never completed for various reasons, not the least of which was a Department of Justice antitrust lawsuit alleging that Fox-Loew’s would have an oppressive 40 percent market share—the same number estimated for the proposed Disney-Fox merger.

Does the government remember its history lessons? Perhaps: the U.S. Justice Department has refused to rubber stamp the AT&T Time Warner deal and a court date has been set for March 19. One hopes that the proposed Disney-Fox merger will also undergo rigorous scrutiny. Consolidation may make life easier and richer for big media owners, but history advises that competition better serves the rest of us.