The failed president who almost got ousted

Who’s the most vulgar, racist, thin-skinned, vituperative U.S. president?

As a historian of Reconstruction, I’ve always believed that it was Andrew Johnson. However, considering his astonishing first year in office, I’d contend President Donald Trump may soon own this dubious distinction.

The two have much in common. Like Trump, Johnson followed an unconventional path to the presidency.

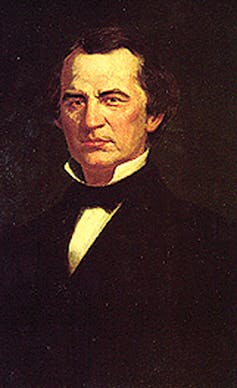

A Tennessean and lifelong Democrat, Johnson was a defender of slavery and white supremacy but also an uncompromising Unionist. He was the only U.S. senator from the South who opposed his state’s move to secede in 1861. That made him an unconventional yet attractive choice as Abraham Lincoln’s running mate in 1864 when Republicans took on the mantle of the “Union Party” to win support from Democrats alienated by their own party’s anti-war stance.

Six weeks after becoming vice president, an assassin’s bullet killed Lincoln and catapulted Johnson to the presidency.

Republican reception mixed for Johnson

Like Trump, Johnson entered the White House with a mixture of skepticism and support among Republicans who controlled Congress. He was a Southerner and a Democrat, which concerned them. But his courageous Unionism and blunt criticism of rebels – “Treason must be made infamous and traitors punished,” he proclaimed – impressed congressional leaders, who believed that he would take a firm approach to the South.

The Republicans soon learned that they were mistaken.

Through bold assertion of executive authority, Johnson quickly reconstructed state and local governments in the South. Because African-Americans were excluded from the process, these regimes were controlled by Southern whites, most of whom had been loyal Confederates. Predictably, they adopted laws designed to keep African-Americans in a servile position.

Southern officials also stood by and even abetted whites who unleashed a wave of violence against former slaves. For example, in July 1866, New Orleans police participated in a massacre that left 37 African-Americans and white Unionists dead and more than 100 wounded.

Unlike today’s Republicans, most of whom have become more loyal to Trump, Reconstruction-era Republicans pushed back against Johnson. They viewed emancipation as a crowning achievement of Union victory and were determined to ensure that former slaves enjoyed the fruits of freedom. Although they hoped to avoid conflict with the president, in early 1866, they adopted measures designed to establish color-blind citizenship and protect former slaves from injustice.

No fan of negotiation

Like Trump, Johnson’s instinct was to attack rather than negotiate. A states’ rights Democrat and proponent of white supremacy, Johnson rebuffed Republicans’ efforts at compromise. He responded to Republican civil rights legislation with scathing veto messages. In September 1866, he toured the North, leveling personal attacks against congressional leaders and seeking to rally voters against them in the midterm elections.

Growing up poor and illiterate, Johnson had developed a deep hostility for African-Americans, believing that they looked down on people like him. His private conversations were laced with racist invective. After meeting with a delegation led by the black leader, Frederick Douglass, for example, he exclaimed to his secretary, “I know that damned Douglass; he’s just like any n—-r, and he would just as likely cut a white man’s throat as not.”

In speeches on the campaign trail and in Washington, Johnson cast his opposition to Republican civil rights policy in language that today appears clearly racist. He sought to appeal to voters — North as well as South – who felt threatened by African-American gains.

In vetoing the Civil Rights Act of 1866, Johnson argued that African-Americans, who had “just emerged from slavery,” lacked “the requisite qualifications to entitle them to the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States.” Indeed, he asserted, the law discriminated “against large numbers of intelligent, worthy, and patriotic foreigners [who had to reside in the U.S. for five years to qualify for citizenship] in favor of the negro.”

Made excuses for Southern racism

Johnson excused racist violence in the South. Ignoring facts that had been widely reported in the press, Johnson held Republicans in Congress responsible for encouraging black political activism during the New Orleans massacre. That was the July 1866 riot where a white mob – aided by police – set upon African-American marchers and their white Unionist sympathizers, leaving 37 African-Americans and white Unionists dead and more than 100 wounded.

“Every drop of blood that was shed is upon their skirts,” Johnson charged, “and they are responsible for it.” Whites who encouraged blacks to demand the right to vote, not the white mobs and police who attacked them, bore responsibility, Johnson implied.

Like Trump, Johnson fancied himself a populist. He saw himself as a principled defender of the people against Washington insiders bent on destroying the republic. By refusing to seat senators and representatives from the reconstructed states of the former Confederacy, he charged in 1866, congressional leaders were riding roughshod over the Constitution.

“There are individuals in the Government,” Johnson told an audience in Washington, D.C., “who want to destroy our institutions.”

Later, when confronted by catcalls from Republican partisans, Johnson fired back.

“Congress is trying to break up the Government,” he said, casting congressional leaders as enemies of the Union in the mold of secessionist heroes Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee.

Combining egotism, victimhood and paranoia in a manner similar to Trump, Johnson portrayed himself as the nation’s much maligned savior.

“I am your instrument,” he told one audience. “I stand for the country, I stand for the Constitution.”

Johnson saw his opponents as enemies bent not just on impugning the legitimacy of his presidency but whose “intention … [is] to incite assassination.” In a melodramatic and revealing pledge, he proclaimed, “If my blood is to be shed because I vindicate the Union … then let it be shed.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Johnson’s presidency ended badly.

Reviled by African-Americans

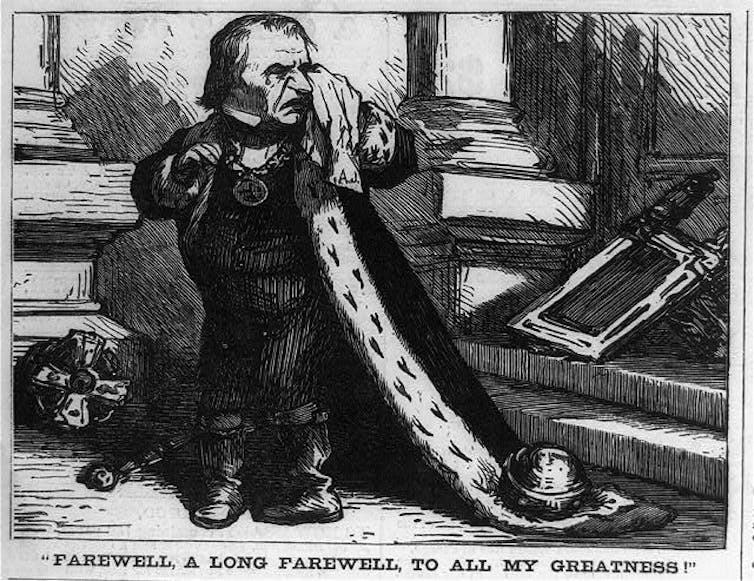

While lauded by white Southerners, he was reviled by African-Americans and most Northerners for disgracing the office of the presidency. Thomas Nast, the popular political cartoonist, lampooned him, the press chastised him and private citizens expressed their disgust.

Commenting on Johnson’s electioneering tour of the North, Mary Todd Lincoln said acidly that his conduct “would humiliate any other than himself.”

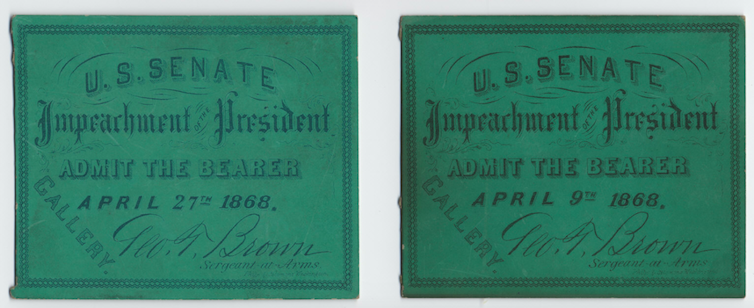

Congressional Republicans overrode Johnson’s vetoes and tied his hands on matters of policy. In 1868, the House of Representatives voted to impeach him but the Senate fell one vote shy of the two-thirds majority necessary to remove him from office.

As his term came to an end in 1869, his successor, Ulysses Grant, refused to ride to the inauguration in the same carriage as the disgraced Johnson, who then declined to attend the ceremony. Instead, he remained at the White House, leaving it for the last time to go to his Tennessee home — and perhaps a more receptive audience of like-minded Southerners — after the inauguration was over.

Presidents succeed by appealing to shared values, uniting rather than dividing, making strategic use of the respect Americans have for the office, and avoiding the gutter. Andrew Johnson failed on all counts, destroying his presidency and bringing himself into contempt.

The Washington Post’s Senior Editor Marc Fisher writes that Donald Trump learned as a real estate developer and entertainer “that what humiliates, damages, even destroys others can actually strengthen his image and therefore his bottom line.”

![]() Will those lessons serve Trump well as president? Or will they condemn him to Johnson’s ignominious fate?

Will those lessons serve Trump well as president? Or will they condemn him to Johnson’s ignominious fate?