How Guns Have Destroyed American Idealism

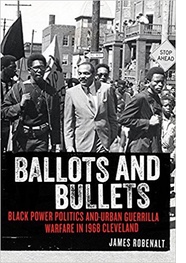

Boris Yaro's photograph of Robert F. Kennedy lying wounded on the floor immediately after the shooting - By Source, Fair use

Perhaps there is no coincidence that in the same week that the Department of Justice confirmed Russian interference with the 2016 presidential election, seventeen young Americans were gunned down by a troubled young man who had easy access to a military-style rifle.

The people who cry the loudest about

protecting themselves from the government through possession of their

guns look the other way when a politician and his son engage in what

many think is treasonous activity with the Russians. So long as that

politician pledges to save their guns—and explain away every mass

shooting—these NRA fanatics care little about the rancid attack on

our democratic system of government.

The people who cry the loudest about

protecting themselves from the government through possession of their

guns look the other way when a politician and his son engage in what

many think is treasonous activity with the Russians. So long as that

politician pledges to save their guns—and explain away every mass

shooting—these NRA fanatics care little about the rancid attack on

our democratic system of government.

But the corrosive effect of guns on our democracy has a long and sickening history. Guns have destroyed American idealism.

Fifty years ago, a man murdered one of our greatest sons with a high-powered rifle in Memphis. In so many ways, Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream died with him. Dr. King was thirty-nine years old. It is hard to comprehend how much he accomplished in his short life, but even harder to grasp how much we lost when that one bullet transected his spinal cord and left him prostate on a hotel balcony. We cannot begin to measure the loss.

When he was gunned down, Dr. King was planning his Poor People’s Campaign. Conceived as a modern day camp-in much like the Bonus Army assemblage of World War I veterans who descended on Washington, D. C., in the summer of 1932 to demand cash payment of their service certificates, Dr. King envisioned a march originating out of the South of legions of poor people who would stay in the nation’s capital until Congress passed antipoverty legislation.

Dr. King had come a long way from his days in opposing Jim Crow laws. From his brief experience in northern ghettos, beginning in Chicago in 1966, Dr. King began to see his mission as greater than civil rights. He expanded his vision to all America’s poor. Henceforth, his cause was not just about the right to vote or where one might sit on a bus, it was about human dignity and human worth. In a country overflowing with resources and wealth, there was no excuse for poverty.

In this new undertaking, Dr. King was joined by New York Senator Robert Kennedy. President Johnson had made the “war on poverty” a keystone of his Great Society, but his credibility and legitimacy were drained by his gross error in escalating American involvement in the Vietnam War. So Bobby Kennedy joined the race, injecting new hope, energy and youthful optimism into a presidential contest that had been a dirge, as LBJ and Richard Nixon trudged their way to the expected nominations of their parties.

Gun violence ended it all within two short months in 1968.

On March 31, Dr. King was invited by the dean of the National Cathedral to deliver a sermon to Washingtonians. The dean was Francis Sayre, born in the White House as Woodrow Wilson’s first grandson. Sayre wanted to provide Dr. King with a forum to reassure the citizens of Washington that his poor people would not bring violence with them.

Dr. King needed to make this speech because he had joined a march in Memphis to protest the working conditions of city sanitation workers, but it was a rally he had not planned and it eventually got out of hand when adolescents began rioting in the streets. One young black male was killed.

King was determined to prove that the violence was an isolated incident, one that could be managed in a second march that he and his people would carefully organize. Thus, he planned to return to Memphis on April 3.

But before returning to Memphis, he gave his last sermon in the National Cathedral. He spoke about the needs of the poor and how Jesus had indicted people of means not because they were wealthy, but because to them the poor were invisible.

“We are not coming to tear up Washington,” Dr. King told his audience. “We are coming to demand that the government address itself to the problem of poverty.”

He explained himself: “We read one day, ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.’ But if a man doesn’t have a job or an income, he has neither life nor liberty nor the possibility of the pursuit of happiness. He merely exists.”

That night, Lyndon Johnson told a national TV audience that he would not run again for president. He undoubtedly was shaken by Senator Eugene McCarthy’s strong showings in initial primaries, but more likely he feared the entrance of Bobby Kennedy into the campaign just two weeks earlier.

Dr. King returned to Memphis days later and gave one of the most prophetic speeches of American history when he all but predicted his death the next day. “Longevity has its place,” he said as portentous thunderstorms rattled around the Memphis region, “ but I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will.”

The night Martin Luther King Jr. was killed, Bobby Kennedy was in Indianapolis, but he was scheduled for a major campaign appearance in Cleveland the next day. He and associates stayed up much of the night composing a short address he would deliver to a packed house in a hotel ballroom where a special session of the City Club of Cleveland was scheduled.

Known today as the “mindless menace of violence” speech, much of RFK’s short 10-minute talk was on gun violence in America. “What has violence ever accomplished? he asked. “What has it ever created? No martyr’s cause can ever be stilled by an assassin’s bullet.”

He called a sniper a “coward” and an uncontrolled mob “the voice of madness, not the voice of reason.” “Yet,” he admonished, “we seemingly tolerate a rising level of violence that ignores our common humanity and our claims to civilization alike. We calmly accept newspaper reports of civilian slaughter in far-off lands. We glorify killing on movie and television screens and call it entertainment. We make it easy for men of all shades of sanity to acquire whatever weapons and ammunition they desire.”

Two months later, Robert Kennedy was himself the victim of gun violence.

And he was wrong about the toll of gun violence: it has killed the martyr’s cause. Richard Nixon won the election in 1968 and began to dismantle the Great Society and the nation’s war on poverty. From his time until now, the nation has turned from addressing the root causes of poverty to a “lock them up” mentality. The number of black men in prison has grown exponentially.

Nixon’s cynical “law and order” administration resulted in many of his highest officials, including the Attorney General, going to jail, mainly over obstruction of justice charges and lying to investigators.

We see a repeat in the Trump administration.

Our democracy cannot tolerate treason with the Russians, just as it cannot survive the pernicious impacts of gun violence. Fifty years ago, guns took some of our greatest leaders, men who gave moral meaning to our national purpose and hope to the hopeless. We have not seen their likes again.

And now this Congress and President watch mindlessly as our children are slaughtered, not as Bobby Kennedy said in “far-off lands,” but in our own neighborhood schools.

How can we possibly measure these losses?