Hiding Behind the Second Amendment Is a Nasty Scam and Misunderstanding of American History

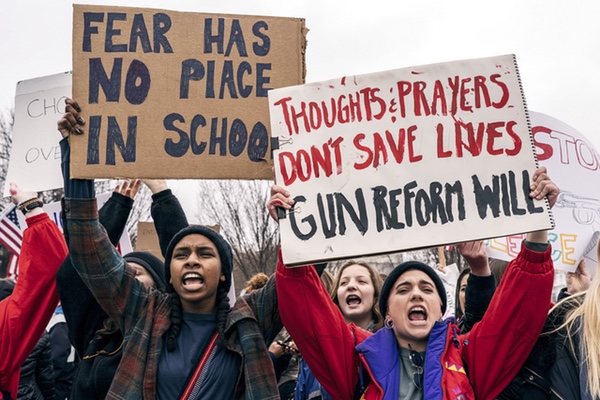

Students protesting gun violence at the White House, February 19, 2018 - By Lorie Shaull, CC BY-SA 2.0

The Second Amendment to the Constitution has tremendous symbolic importance but is of no practical value in thinking about gun control. After the key events of August-October 1794, which people know as the Whiskey Rebellion, the basic issues behind the adoption of the Amendment could be considered resolved: the United States would continue to have a regular, standing army; the federal government would exercise the right and obligation to suppress local rebellions; and only government-authorized troops would possess heavy weapons designed for military use.

Here is the entire Amendment, in its unstandardized eighteenth-century capitalization and free use of commas:

“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

The tension between the two parts of the sentence has led to endless, pointless debate about whether the right to bear arms is a public one related to the militia or a private right of individuals. That argument will never be resolved. It is necessary to move on.

Before looking more closely at the critical year 1794, a brief review of recent court decisions and laws on bearing arms is in order. Let us start with the wisdom of a “Conservative Legal Titan” (The Heritage Foundation’s accolade), the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. In the majority opinion he wrote for District of Columbia v. Heller, 2008, Scalia stressed that,

Like most rights, the Second Amendment right is not unlimited. It is not a right to keep and carry any weapon whatsoever in any manner whatsoever and for whatever purpose: For example, concealed weapons prohibitions have been upheld under the Amendment or state analogues. The Court’s opinion [recognizing, for the first time, a private right to bear arms protected by the Amendment] should not be taken to cast doubt on longstanding prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, or laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings, or laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms.

Justice Scalia thus not only accepted existing gun controls in The United States, he held the door open for further restrictions. It is not possible, as he well knew, to buy a hand grenade or a cannon, or to possess a fully automatic weapon except in narrowly specified circumstances. In most states, children many not purchase guns. Therefore the idea that the debate over firearms is between “gun rights” groups and “gun control” advocates is sterile. The question before us is what kind of controls and restrictions of firearms are right and proper.

After the massacre on February 14, the Florida legislature could, as other states have done, ban the sale of so-called assault rifles, raise the age at which any firearm might be purchased, and so on. New York and Connecticut have banned the sale of assault-style weapons and have tried to make it harder for everyone to buy firearms. Recent decisions by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals on concealed carry, as well as the Supreme Court’s refusal to hear appeals from within New York State and Connecticut against restrictions on semi-automatic rifles, show that in the near future, the judiciary as a whole may well look favorably at broader and more rational gun laws.

Yet the events of the summer and fall of 1794 bear heavily on the most fundamental issues of gun possession. The Battle of Fallen Timbers, won by a federal force against an Indian coalition, took place in the Ohio territory on August 20. The Whiskey Rebellion, centered in western Pennsylvania, collapsed by October 24 as a federalized militia–as permitted by the Constitution—arrived in the area.

These two actions established several principles of federal power once and for all. Note that I am not speaking here of matters of right and wrong or justice, nor of the class conflicts which lay behind early republic uprisings, but only of power.

Fallen Timbers showed that, in contrast to earlier ignominious defeats by Indians, victory over them could be won by a standing, well-trained army. The end of the Whiskey Rebellion, a confused rising of farmers who hated a new federal tax on the liquor they made, cemented two principles: one was that taking up arms against national policy and hence against the federal government by a self-appointed group would be termed a rebellion, not a revolution. Actually, that same point had already been made in 1786-87 during Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts. But that affair remained within one state; the Whiskey Rebellion made the principle national.

President George Washington, a long-time land speculator in the “West,” and never a friend of the rough whites on the frontier, whom he called barbarians, led the federalized militia for a time against the Whiskey rebels, with Alexander Hamilton at his side. A force of some 12,000 men, called to federal duty from the official militias of several states, moved toward the scene of the trouble from Philadelphia. Upon learning that this army was on its way toward them, the disgruntled farmers dispersed.

The second major idea established during the Whiskey Rebellion was that the central government alone would hold arms intended solely for military use. The rebels prudently avoided the army garrison at Fort Lafayette (or Fayette), Pittsburgh, which was equipped with cannon, and which in all likelihood would have used that artillery against the farmers.

Thomas Jefferson complained that Hamilton had raised the army for his “favorite purposes of strengthening government and increasing the public debt, and therefore an insurrection was announced and proclaimed and armed against and marched against, but could never be found.” His last assertion was correct in a sense, as the rebels faded away before fighting could take place. Nonetheless, major constitutional issues had been at stake.

The violent events of August-October 1794 put to rest the old idea that the United States could not and should not have a standing army. In the heated discussions by patriots before during, and just after the Revolution, such an army had been branded an instrument of tyranny. But Fallen Timbers alone demonstrated that the new country had to have a permanent armed force. Another hoary principle, or rather a theory, fell by the wayside with the Whiskey Rebellion. Many voices argued in the 1770s and ‘80s that the citizenry had the right to make a revolution against a bad government. The Virginia Bill of Rights, developed in 1776 and later a model for the Constitution, maintained that “a majority of the community hath an indubitable . . . right to reform, alter, or abolish” an oppressive government.

The American rebels against the British crown needed to make such statements in defense of their own right to disloyalty. But the Whiskey Rebellion raised the question of resistance in a republic, where elections, however limited in eighteenth-century fashion to propertied white males, determined not only leadership but the form of government as well. How could anyone tell that a movement of resistance to a democratic government was a revolution and not a mere rebellion? In 1794, the answer was clear to most of the country’s leaders: even though the Whiskey Rebellion, or its sentiments, also erupted in western Maryland and as far south as western North Carolina, it failed to spread widely enough to qualify as even a nascent revolution. And, in reality, the federal government could act to prevent a rebellion from growing into a revolution.

That point leads to the question of what makes a revolution in any event. Successful ones–in the sense of fundamentally altering the form and foundational principles of government–have depended above all, at least since 1789, on the unwillingness of the official instruments of coercion to uphold the existing regime. In the spring of that first year of the French Revolution, the French Guards, the internal security troops of the monarchy, went over to the side of “the nation.” The Old Regime’s ability to control the situation disintegrated. In Russia’s February Revolution, army units, including Cossacks, joined the crowds demonstrating in the streets of Petrograd. Not a single Russian front commander responded to an order from Tsar Nicholas II to march on the city and put down the “disorders.”

It was not “the people” by themselves who won in any sense in Paris or Petrograd, but the people together with deeply disaffected regular forces of coercion. The only path to a new American revolution would be through recruiting similarly demoralized police and troops. That is not in prospect. Revolutions also need ideologies, however inchoate they are at first; a new American revolution would have to espouse something along the lines of total individual freedom–an illogical and impossible position–leavened with hatred for minorities. The forces arrayed against such ideas, even among the great majority of whites, are too powerful to allow broad acceptance of such an ideology here.

Yet today, various well-armed militant groups point toward a new revolution. One is Georgia’s 3 Percenters, who argue that a mere 3 percent of Americans, rushing from their homes with their muskets, successfully defeated the British in our Revolution. Like-minded organizations across the country are training for what they call self-defense against existing government. At times, their agenda is more openly stated. Mike Vanderboegh of Alabama became an important “militia” figure after the 1993 disaster in Waco, Texas, involving Branch Davidian cultists and the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms. Vanderboegh then issued a manifesto called “Strategy and Tactics for a Militia Civil War.” On April 19, 2014, he gave a speech in Bunkerville, Nevada in support of Cliven Bundy’s right to graze his cattle on public land for free. “I proclaim to the world,” Venderboegh said, “to all the would-be tyrants in this country who would victimize such honest, simple people with their evil corruption, their follies, their schemes of power and their insatiable appetites for other people’s liberty, property and lives – YOU MESS WITH SUCH PEOPLE AT YOUR OWN DEADLY PERIL.” Vanderboegh, a long-time recipient of monthly government disability checks, died in 2016. But of course his ideas live on.

Anti-government extremists frequently say they will fight in defense of the Constitution, and they see support for their position in Article I, section 8: the “militia” is the instrument designated “to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions.” The army receives less attention in the Constitution, although the president is designated as “Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States” (II, section 2). Still, fears of a standing army resulted in the limitation that funds to support an army could only be authorized for two years at a time (I, 8).

Yet the Framers, still very much intact as a group, passed the Militia Acts of 1791 and 1792. These referred to organized militias approved and managed by the states, to be made up of all white males between the ages of 18 and 45.

Later expanded beyond its original racist lines, the militia finally became thoroughly regularized in the Militia Act of 1903, also known as the Dick Act, after its sponsor Congressman Charles Dick. This law aimed to resolve the lack of clarity in the Constitution over who controlled the militia, the federal government or the states. Even though the Constitution authorized the president to call up the states’ militias in an emergency, with the agreement of a single Supreme Court justice–as happened in the Whiskey Rebellion—governors continued to resist such orders. The federal government had to supplement the regular army with volunteer militia units, including Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, as late as the Spanish-American War. The Dick Act created the National Guard to resolve the question, once again in favor of the central government. From 1903 on, the Guard has been both an internal security force and an additional reserve, as a national militia organized on a state-by-state basis, for the Army.

That is what became of the Constitution’s militia. No armed “body of the people,” a phrase often used by the Framers, exists today. Self-proclaimed “militias” have no basis in the Constitution.

In recent years, irregular “militia” members have killed police, for instance in Arkansas in May of 2010. Jerry and Joe Kane, father and son “sovereign citizens,” shot two officers who had pulled them over on an interstate highway. Such anti-government groups are not likely to win over the regular forces of coercion by killing some of them.

With all this in mind, there is a way forward to more rational gun control through the Second Amendment and a close look at that critical year in American history, 1794. (1) Gun control is a long-established principle and practice in the U.S. (2) Military-type weapons have no place in the hands of private citizens, at least where they can be used in public. Assault rifles, and indeed any semi-automatic weapon, can be banned or confined to closed ranges for sport shooting. (3) Citizens do have a right, as the clumsy Second Amendment states, to keep and bear arms. What kind of arms is the question; why not adopt the notion of some gun magazines and websites, that a revolver is a better choice for personal self defense than a semi-automatic weapon? A “wheel gun” is much less likely to jam than a semi-automatic, which must be cleaned and oiled regularly to work properly. Revolvers are slower to fire and to reload, giving the public more protection from mentally disturbed shooters, while giving good guys a reliable chance to shoot. Nor is there any self-defense need for a large magazine. In the hands of an untrained and frightened person, a shotgun is far better for home defense than a pistol is. Semi-automatic weapons are not needed for hunting; a simple bolt-action rifle or a shotgun is enough. (4) Let each gun owner be restricted to a certain number of rounds at a time, say 12, a number that again provides for self-defense. Israel limits gun owners to 50 rounds a year. We can do that, although the task of reducing the 10-12 billion bullets and shells purchased each year in the U.S. to a manageable number will be immense. But there is no longer any excuse for not starting the process.

Numerous foreign models for rational gun control are available, for example Australia’s. Strict laws and a gun buy-back program there adopted from 1996 through 2002 have so far ended mass shootings and have played a major role in reducing homicides–although right-wingers here and President Trump deny that fact. Australia is no less free today–indeed, if we consider that the prospect and the fact of gun massacres in America are grave violations of our rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, then Australia is freer than our country is.

Hiding behind the Second Amendment to advocate few or no restrictions on firearms is a nasty scam and misunderstanding of American history. Although the path to reasonable gun control will be long, extremely hard, and even dangerous for its advocates, we have every reason to start on that task.

________

Recommended Reading

Michael Waldman, “How the NRA Rewrote the Second Amendment,” Politico, May 19, 2014.

John Ferling, Jefferson and Hamilton, 2013.

Thomas P. Slaughter, The Whiskey Rebellion, 1986.

David C. Williams, The Mything Meanings of the Second Amendment, 2003.