Why It’s Dangerous to Give in to Facile Analogies Between the Last Gilded Age and Our Own

Historical analogies are inevitably imprecise, but it is now commonplace and not inappropriate to link our own times to that of the turn of the twentieth century as a second Gilded Age. What we invoke at either end by doing so is the image of a society of growing economic inequality and ostentatious wealth as well as the despair or anger of people caught in the middle and feeling that the political institutions around them are only making things worse. In recognizing a common social and economic predicament across time, however, we are less likely to appreciate an analogous spatial reach of the two eras. My book, The Long Gilded Age: American Capitalism and the Lessons of a New World Order sets the First Gilded Age of growing social division in the U.S. in a wide geographic frame—contrasting the American pattern of class and ethno-racial fragments, law and industrial relations, mass education, and radical thinking with those of other western countries. In the process the book also explores the consequential contributions of those whose experiences in the U.S. were shaped by lessons learned abroad.

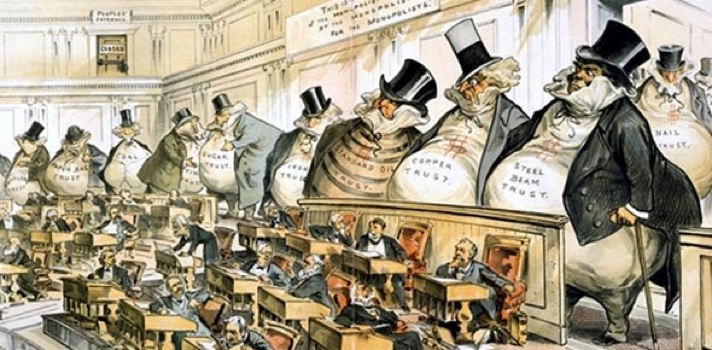

Alas, one danger of these historical

doppelgangers is the tendency to react—as readers or observers—to

the trend lines of both eras with self-righteous scorn or an

ultimately immobilizing cynicism. Textbook accounts of the First

Gilded Age thus too easily conjure up the stick-figure actors of the

scrooge-like industrialist, the poor and exploited worker, and the

kindly but condescending settlement house reformer; such examples fit

all too comfortably alongside contemporary images of a runaway global

elite, a helpless (if self-immolating) precariat, and moralistic but

ineffectual media scolds. How, in short, can we insert a more

useful, less dismissive and judgmental analysis of the world around

us?

Alas, one danger of these historical

doppelgangers is the tendency to react—as readers or observers—to

the trend lines of both eras with self-righteous scorn or an

ultimately immobilizing cynicism. Textbook accounts of the First

Gilded Age thus too easily conjure up the stick-figure actors of the

scrooge-like industrialist, the poor and exploited worker, and the

kindly but condescending settlement house reformer; such examples fit

all too comfortably alongside contemporary images of a runaway global

elite, a helpless (if self-immolating) precariat, and moralistic but

ineffectual media scolds. How, in short, can we insert a more

useful, less dismissive and judgmental analysis of the world around

us?

One answer is the construction of a kind of historical counter-factualism, or, within the transnational webbing of The Long Gilded Age, what I call exercises in “grounded globalism.” Why, we might ask of actors at a particular place in time, not only what they did but what, within the range of conceivable contemporary options, they might have done differently?

As a prime example, I take up the case of Scottish-born employer/philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. Images of Carnegie are often split between the good works (especially libraries) of this dewy-eyed apostle of American greatness and his no-holds-barred destruction of the nation’s leading labor union, the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers, in the bloody Homestead strike of 1892. In his own mind, Carnegie, as the son of a failed handloom weaver, had taken his own self-made social assent as the prerogative of any ambitious soul within the “free” and “democratic” American Republic, and he had no patience for workers (especially those from “lower”-immigrant stock) who could not on their own follow his example. While some are apt to dismiss his philanthropic work more as legitimation than the obligation of the rich as articulated in his “Gospel of Wealth” talk of 1889, I think we are better served by a more complex appraisal. To be sure, his refusal to negotiate with his men, followed by a lock out and resort to a private army to protect strikebreakers forever stains his reputation. Yet, it is also true that such unilateral resort to force was perfectly legal in a country whose laws and courts had safeguarded property and the right of individual contract above any other community norm.

The fact is, however, that far from taking the imbalance of their society as a done deal, Gilded Age Americans were caught up in a great struggle. A closer look at the politics of the times, for example, reveals a sustained attempt to re-balance social relations in a way that would curb industrial violence by recognizing group as well as individual contract rights and guaranteeing workers, through their unions, a seat at the table. In short, various systems of compulsory arbitration (often involving special labor courts) had proved of effective service in Australia, New Zealand, France, and most other industrializing countries. Their lessons, both for industrial peace and worker justice, were much discussed by American observers, including legislators. Beginning with advocacy from the Knights of Labor in the 1880s and continuing through official inquest into the Pullman strike of 1894, the cross-class consensus of the National Civic Federation (NCF) in 1900, the “protocols” of the New York and Chicago garment industry in 1910-1911, the findings of the U.S. Commission on Industrial Relations, 1912-1914 and finally, consummation (albeit temporary) in the National War Labor Board of 1918, a fledgling system of government-sanctioned conciliation and arbitration was erected alongside the raw test of power otherwise betokened in a putatively free enterprise economy.

It is worth noting that Carnegie himself became something of a convert to the cause of arbitration. Dusting off his old, British-Liberal anti-imperialist credentials by opposing the U.S. annexation of the Philippines in 1898 (“Are we to exchange Triumphant Democracy for Triumphant Despotism?”), he soon offered his services in support of several international arbitration treaties, a commitment that would lead to establishment of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in 1910. In the same years he also became a pillar of the class-conciliation-oriented NCF, including providing funds for AFL President Samuel Gompers defense of strike and boycott rights in the Buck’s Stove and Range case.

To be sure, neither in the realm of international relations (as in his frustrated hopes for the League of Nations) nor for the ends of domestic tranquility did Carnegie’s plans come to fruition. War-time labor arbitration gave way to the viciously anti-union “American Plan” of the 1920s. And even as the 1930s and WWII ultimately ushered in a more equitable system of employee rights under the National Labor Relations Act, the initial preferential option for workers’ organized representation under the act succumbed by the 1980s to the old shibboleths of contract law embodied in the individual’s “right to work” and right to choose (under virtually unlimited employer inducement) a “non-union” environment. From Bucks Stove to the Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association case, now before the Supreme Court and likely to impose right-to-work principles on public employee unions, a key theme of the First Gilded Age continues to reverberate in the Second Gilded Age.

Still, despite repeated setbacks in the attempt to loosen our country from the inequality and oppression on display in our twin Gilded Ages, we can take heart from the fact that many Americans, indeed whole communities, have long struggled for something better and more decent. Such spirit was exemplified by the striking schoolteachers in West Virginia, defying state budget cuts, even as it was by the steelworkers of Homestead in 1892. Moreover, even the “villains” in such dramas, like Carnegie, have shown that they can learn new lessons. This is no time for resignation; the book, after all, is not yet written for the Second Gilded Age. "Let America be the dream that dreamers dreamed” chanted poet Langston Hughes. It is surely worth the effort.