Arbitration as a way out of the North Korean crisis

According to latest polls, a majority of Americans see North Korea as the greatest immediate threat to the U.S. with as many as 73 percent concerned about Kim Jung Un’s use of nuclear weapons. The world lives in fear that one more provocation in the form of a North Korean missile or nuclear test could lead to major war on the Korean Peninsula.

It is true that tensions have lessened recently with North and South Korea holding talks and, on March 8, President Trump accepting an invitation to meet with North Korean leader Kim Jung-Un “by May.”

But past efforts to engage the North have often left participants unsatisfied and disappointed. If these talks fail or lead to frustration, the temptation to resort to military force could ratchet up quickly. And if such direct engagement efforts fall short of expectations, international arbitration might provide – as it has in the past – an alternative to conflict.

As scholars who study international law and Asian politics, our question is: Could arbitration help resolve the present crisis with North Korea?

We have been here before

In 1904, war between Russia and the United Kingdom appeared imminent after the Russian Baltic fleet fired on and severely damaged six English fishing boats, killing two fisherman and wounding six others, on Dogger Bank, just a few miles off the coast of England.

The British press demanded that the “wretched Baltic fleet” be destroyed, and the Royal Navy eagerly maneuvered to do just that.

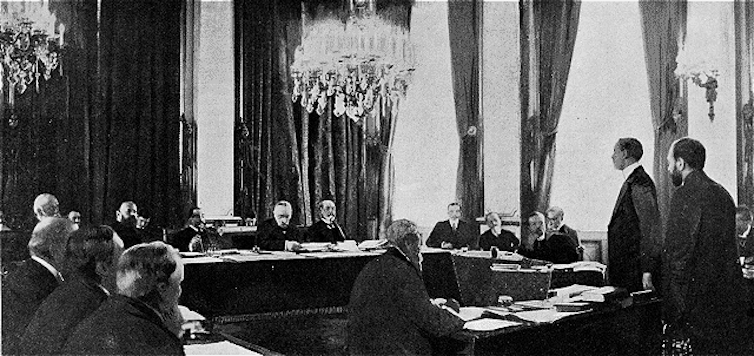

War was avoided at the last minute when the foreign ministers of both countries agreed to arbitration presided over by commissioners from Britain, Russia, the United States, France and Austria.

The result was a four-month interval that allowed time for tempers to cool as well as a complete inquiry and an analysis of the incident.

Ultimately Russia paid damages for the incident on Dogger Bank, and the U.K. and Russian governments were both able to step away from war while saving face with their public.

A positive track record

The United States, too, has been party to disputes settled by arbitration.

The most prominent of these are the “Alabama claims” in which the U.S. – after the Civil War – demanded reparations from the U.K. for having supplied and armed Confederate ships such as the CSS Alabama, despite being ostensibly neutral. These “Confederate raiders” had caused millions in damages to American shipping. Such was the tension between the two countries that some American politicians suggested that the U.S. annex Canada, which was then under British rule.

Instead, diplomacy prevailed and the U.S. and the U.K. finally agreed in 1871 to an arbitration panel – composed of Switzerland, Italy, Brazil, U.S. and the U.K. – that awarded US$15 million to Washington and, critically, also set the stage for a lasting peace between the two countries.

After this arbitration, politicians, including Ulysses S. Grant, thought the world could be entering an “epoch when a court recognized by all nations will settle international differences” so as to avoid major military conflict.

Indeed, such a court was created in 1899 at the Convention on Pacific Settlement of International Disputes and still exists with the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, which has been actively involved in settling current disputes in India, Malta, Italy, Timor, Australia and South Africa.

Given this positive historical track record, could arbitration help avoid war on the Korean Peninsula today?

Why it could work

This is not far-fetched.

It is impossible to underestimate the enmity between Russia and the U.K. in 1904 or England and the U.S. in the mid-19th century, but arbitration still took place. All three of these countries were also extremely nationalistic in an age of great power expansion. Their concept of individual sovereignty was not unlike that which kept the U.S. in the 20th century from signing on to international conventions such as the U.N. Law of the Sea and the International Criminal Court.

What it took to get to arbitration, in the case of Dogger Bank, was a third party like France concerned about being dragged into a larger conflict – think China today – and individual government officials who were willing to honestly seek peace.

So, assuming that there would be willingness on the American and Korean sides to this, how might it work?

How it could work

One advantage of such a commission is that it could make relatively objective, logical and practical decisions that politicians could never agree to if they wanted to keep their popular base and their defense establishments happy.

For example, it is likely that President Donald Trump could not, at present, agree to let North Korea keep nuclear weapons. At the same time, despite what Kim Jong Un has told the South Koreans, his generals would probably not be happy with a unilateral promise to cease testing in the Pacific.

Supporting an international arbitration mechanism would certainly offer China a tempting opportunity to restore its international legal image following its rejection of the 2016 U.N. ruling against it and its claims in the South China Sea.

So who would sit on this arbitration panel? We believe it would make sense to decide this on the basis of the U.N. Security Council’s permanent members and the leading countries in the region: China, Russia, France, the U.K. and Japan.

The next question is, what would such an arbitration court decide?

A possible outcome

There are many possible scenarios, but we believe the following would be realistic, fair and effective.

Many countries – from France, the U.K and the U.S. to India, Israel and Pakistan – have nuclear weapons. Their primary motive is not aggression but self-preservation. It seems reasonable that this is North Korea’s main motivation too. All nations today are also acutely aware of what happened in Libya to Gaddafi and in Iraq when Saddam did not have weapons to defend against invasion. North Korea, therefore, could make a case to keep its present stock of nuclear weapons. Although South Koreans have reported a willingness on Pyongyang’s part to give them up, this remains one of the most contentious elements of any resolution.

North Korea would freeze its intercontinental ballistic missile program (those missiles with minimum range of 3,400 miles or 5,500 km) and promise not to further test nuclear weapons or to fire their missiles toward or over any other nations.

China would promise to come to the aid of North Korea if invaded – after all, it has come to its aid before, in 1950, during the Korean War.. But, critically, the Chinese would also promise that if North Korea acted unilaterally or distributed its nuclear weapons to third parties, then China would back the elimination of the present regime.

This last promise would be heralded as a serious shift in China’s strategy and would send an unambiguous message to the North Koreans while simultaneously signaling China’s constructive engagement in favor of stability on the Korean Peninsula.

The point is that North Korea does not want China as an enemy. China, for its part, is loathe to see a nuclear-armed North Korea. For a number of years, China has felt that it has lost a good deal of influence and control over its North Korean ally. This sort of declaration from China would help restore China’s influence while simultaneously reining in the Kim regime.

Protecting the US

President Trump’s desire to put America first seeks to avoid getting bogged down in unnecessary foreign entanglements such as a significant war on the Korean Peninsula.

At the same time, the president has an obligation to protect and defend the United States from a potential nuclear threat.

![]() Although the arbitration route could be vulnerable to domestic political critiques of “outsourcing sovereignty” it might, nonetheless, offer a way out of the current menu of unpalatable options. It is certainly far better than a disastrous war.

Although the arbitration route could be vulnerable to domestic political critiques of “outsourcing sovereignty” it might, nonetheless, offer a way out of the current menu of unpalatable options. It is certainly far better than a disastrous war.

Ronald Sievert, Senior Lecturer in Government, Texas A&M University and William Norris, Professor of Chinese Foreign and Security Policy, Bush School of Government and Public Service, Texas A&M University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.