That Famous Pitchfork: An Artist’s View of Depression Era America

As any American who Grant Wood was and only a handful will know.

Then ask them about the painting, “American Gothic” and most will say, “Oh, yes. Of course! The couple and the farm and the pitchfork.”

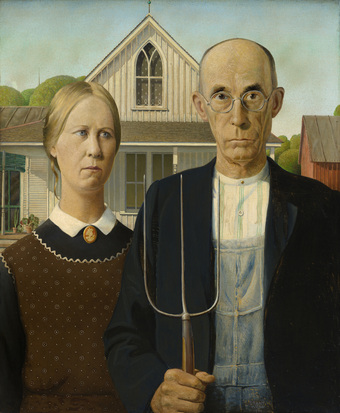

The classic painting of a grim looking man and woman, the man with the pitchfork, standing in front of a farm house in the Midwest in 1930, so familiar to all, has been called “America’s Mona Lisa” and justifiably so.

The painting, by Grant Wood, is a triumph. The tragedy is that he is only known for that work when, in fact, he drew hundreds of paintings and sketches about life in the Midwest in the 1920s and thirties, gorgeous, memorable pieces of art that are just unforgettable when you see them and yet he remains famous for that one, single, work.

The Whitney Museum, on Gansevoort Street, in New York, wants to change all of that. The museum just opened up an absorbing exhibit of Wood’s work. It devoted several large galleries to his paintings and, together, they tell a marvelous story with vivid colors of tough, resolute Midwesterners determined not only to survive the Depression in the 1930s, but to prevail over it.

One of the first paintings you see when you walk into the exhibit is a lustrous sketch of a colonial era mansion in a deep green forest. Out front is a man riding a horse, waving his hat to the home’s inhabitants. It is gorgeous and a fine opening to this historic look at the Mid-west.

There are numerous portraits of women over the years that are of photograph clarity. His mother, whom he called “a pioneer of the mid-west” is featured in one of them. His Great Aunt, small chin and very somber, is in another.

There are all kinds of paintings from the past, such as George’s Washington’s dad scolding him for chopping down the cherry tree and not one, but two paintings of President Hoover’s birthplace. There is Wood’s beautiful version of the midnight ride of Paul Revere, with a huge church steeple as the centerpiece. There are is a 1920s portrait of a boy, around ten, holding a football, a man swinging a golf club, a boy carrying a basket of corn, a woman trying to buy a chicken held by a man. There are numerous paintings of all or parts of Depression era Iowa farm villages, with a from-the-air vantage looks. There are several large and colorful sketches of rolling Iowa farm fields and meadows. Wood painted a majestic portrait of the tiny town if Stone City, Iowa, with its quaint bridge, in 1930. There are a few paintings that depict springtime in small Iowa villages. Wood’s people are very realistic and appear to have just jumped from the room onto the canvas.

The exhibit is a nice tribute to Wood and to his work on the Depression and the people of the Midwest. It really was heartwarming, too, to see the lush summer wonderland of Iowa on a cold day in New York, snow everywhere you looked.

Wood, who lived in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, spent the 1920s trying to copy French impressionist art and made several trips to Europe to study that art form. By the late 1920s, he decided that he could be successful with American paintings, particularly those of farm life and people, using an impressionistic style. What emerged was his very own, strong, American style

“American Gothic” is, of course, the centerpiece of the exhibit, jammed with people on the day that I was there. Two dozen or so people at a time stared at it. The woman in the painting is Wood’s younger sister and the man is his dentist. They are standing in front of a real farm house in Eldon, Iowa. The dentist was thrilled to be in the picture but the sister always complained that he made her look too old. Most people believe they are a pair of married farmers. Most people also feel that the photo is a satire of grumpy, stern Midwesterners, but Wood said they are supposed to represent sturdy, strong Americans.

To show you how much people know of the painting, and how little they know, is this anecdote. A woman with blonde hair, wearing a short blue coat, trailing her husband, stopped in front of the security guard at the entrance to the gallery.

“I want to see the pitchforks. Where are the pitchforks?” she said to the smiling guard.

In front of the work of art itself, where many had their pictures taken, people said the oddest things.

“I wonder if those two are looking west or east?” said one woman.

“How come the woman doesn’t have a pitchfork, too,” said another.

“I wonder how tall they were?” asked a man.

“How hot was it when he painted this?”

“What’s with the pitchfork?” said yet another.

The painting was unveiled in 1930 and became an immediate sensation. Art critics have written about it endlessly, telling their readers that it represented the Midwest, or America, or the nuclear family, or farm life, on the Depression, or rural lifestyle. They have gone on for pages.

A guide at the museum said it best. The woman, in her early twenties, in a dark brown dress, big smile on her face, shrugged when asked by someone why “American Gothic” is so famous.

“I think that there is something in it for everybody. It intrigues everybody but it intrigues them in many different ways,” she said, and she is right. You can’t exactly say why it is so wonderful, but you acknowledge that it is (the painting has appeared in cartoons, newspaper drawings, film and television for decades).

The Whitney curator, Barbara Haskell, did a superb job in both selecting what paintings to use and how to stage the exhibit.

First, it is well organized. There are portrait paintings, farm art, landscape paintings, women, murals, a spectacular, colorful, large stained-glass window he created to honor America’s war dead and even artwork he did for Sinclair Lewis’ book, Main Street. You go room by room to look at them and the order gives completeness to the exhibit. 2) she and her associates wrote detailed descriptions of the work, and Wood, that adorn the walls. When you finish, you learned a lot. 3) she chose works that underscore Wood’s theme all of his life, that Americans are good and strong people and will defeat the Depression, 4) she hung “American Gothic” on one wall, alone, so visitors could get a good look at it, 5) while acknowledging the fame of “American Gothic,” she chose numerous other works that underscore Woods role as a brilliant artist.

Ironically, just behind the exhibit on the fifth floor is an enormous window that offers a spectacular view of Lower Manhattan and the Hudson River that serves as a majestic “painting” itself, a painting Woods might had done himself.

A comic moment in this delightful exhibit: a guide finished talking about paintings of Iowa when an 8 or nine-year-old kid looked up at his mom and said “Iowa does not look at all like New York City.”

No, it does not.

The exhibit will be at the Whitney through June 10.