What We Really Have to Worry About Isn’t Trump

The country is divided into two hostile camps, a division as much geographic as ideological.

On one side are the big cities, the centers of progressive politics and home to social movements for women, for gay people, for minorities, and to an unprecedented wave of immigrants. Many of the immigrants look and dress very differently from residents of longer standing, marking them as followers of a different religious faith. Many are refugees from an unprecedented wave of war and civil war. Many have entered the country illegally.

Then

there are the rural areas. These have always been conservative, but

now economic hard times and a pervasive feeling of humiliation are

driving their conservatism to a new level of anger. People in rural

areas attribute much of this humiliation to urban liberals who seem

to care more about refugees and minorities than they do about their

country cousins. The country people are statistically much more

likely to have served in the armed forces and they feel that their

patriotism contrasts with the deracinated, increasingly foreign

cities. Religious faith, especially evangelical Christian faith, is

central to life in the country. Rural people often see the cities as

nothing but cesspits of every conceivable kind of vice.

Then

there are the rural areas. These have always been conservative, but

now economic hard times and a pervasive feeling of humiliation are

driving their conservatism to a new level of anger. People in rural

areas attribute much of this humiliation to urban liberals who seem

to care more about refugees and minorities than they do about their

country cousins. The country people are statistically much more

likely to have served in the armed forces and they feel that their

patriotism contrasts with the deracinated, increasingly foreign

cities. Religious faith, especially evangelical Christian faith, is

central to life in the country. Rural people often see the cities as

nothing but cesspits of every conceivable kind of vice.

Into this volatile mixture comes a politician who thrives on the exploitation of anger. He tells the suffering rural people that those urban elites, the religious minorities, and much of the rest of the world are responsible for their troubles. He is willing to say things that no other politicians would dare to utter. The rural people respond by giving their votes overwhelmingly to him. Soon the strange new politician is in power.

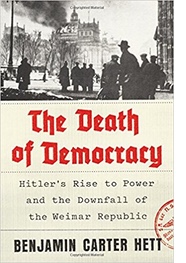

But this is not the United States in 2018. It is Germany in the early 1930s.

Germany’s rural areas had been hit above all by major shifts in the global economy: the opening up of farmland in the new world had caused grain prices to fall dramatically. German farmers struggled to compete, and many went bankrupt. In the First World War the German army had drawn more recruits from rural than from urban areas, because city people were likely to have skills that made it essential for them to remain at home. This meant far more farm boys than factory hands had died in combat. The war ended not only in defeat but also with a democratic revolution that replaced the authoritarian regime of Kaiser Wilhelm II. With democracy, new people moved into positions of power. Some of them were working class leaders who would never have gotten near power before, like the first postwar president Friedrich Ebert, a former saddle maker. Some, like the foreign minister Walter Rathenau, were Jewish. Rathenau was murdered by right-wing extremists in 1922.

We are familiar with the images of Berlin in the “golden twenties” – the sexual experimentation and the artistic creativity. Germany was home to the world’s largest gay rights movement, and it had an active feminist movement that succeeded in winning the vote for German women. But Germany’s cities, Berlin above all, were also the home to a new wave of immigrants. Many of them were Jews fleeing revolution and civil war in Eastern Europe. Some Germans reacted to their presence with virulent anti-Semitism. Germany had a new and winding border with Poland, and it lacked the military and police resources to control it. The border, like the immigrants who crossed it, became a bitter political issue. In desperation, some local governments outsourced border security to private militias, including the infamous Nazi Stormtroopers.

Rural German communities were above all permeated by Christian faith and practice, which historically had tended to be nationalist and prone to anti-Semitism. It was in Protestant rural areas in Germany’s north and east that Hitler and his party, once a fringe movement, began to achieve electoral breakthroughs in the late 1920s. By 1932 they were winning the overwhelming share of the vote in these regions. By contrast the Nazis underperformed electorally in cities like Berlin, Hamburg and Frankfurt.

How worried should we be about these striking similarities and the near future they suggest? History never exactly repeats itself, but as Mark Twain is said to have observed, sometimes it rhymes. Donald Trump is far from being Adolf Hitler 2.0, but he has succeeded by exploiting similar grievances in a similar way. And just like the original, his policies will do nothing to allay the causes of his supporters’ anger, just as Hitler’s dismantling of the rule of law, military buildup, and ultimately war and genocide did not solve the problems of the rural German population.

The real danger may come when a more ruthless and competent politician than Trump realizes he or she can succeed by playing on the same themes.