No Matter How Bad Trump Is at His Job, He’s Unlikely to Be Impeached Unless Congress Can Finger Him for a Crime

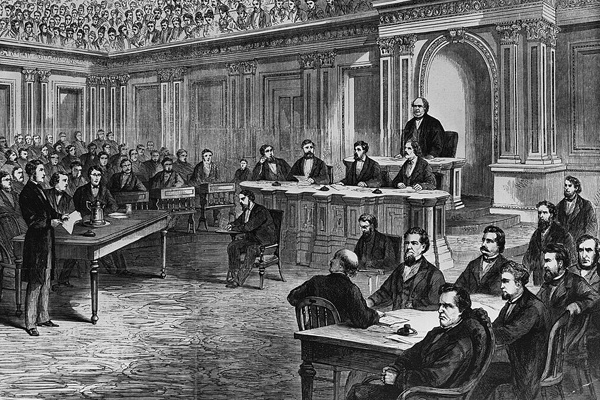

Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

On December 7, 1867, the House of Representatives confronted a one-sentence resolution to impeach President Andrew Johnson for “high crimes and misdemeanors.” Only one day before, the president’s leading defender had lamented that Johnson was “the worst of presidents.” Nonetheless, a large majority of congressmen rejected the impeachment resolution.

This

pivotal episode – which ordinarily is eclipsed by the more dramatic

effort to oust President Johnson several months later –

fundamentally shaped presidential impeachment. Its legacy largely

protects even a president whose conduct can zigzag between the dark

blusterings of a tinpot dictator and zany self-parody.

This

pivotal episode – which ordinarily is eclipsed by the more dramatic

effort to oust President Johnson several months later –

fundamentally shaped presidential impeachment. Its legacy largely

protects even a president whose conduct can zigzag between the dark

blusterings of a tinpot dictator and zany self-parody.

Distraught over our current chief executive, many lawyers, scholars and citizens seek to ignite impeachment efforts through an expansive interpretation of the key constitutional phrase, “high crimes and misdemeanors,” relying on statements by early American leaders. After all, their argument goes, James Madison endorsed impeachment based on a president’s “wanton removal of meritorious officers,” while Alexander Hamilton approved impeachment for “malconduct.” Surely the current incumbent is guilty of both, and a good deal more.

Such arguments might have had some force before December 7, 1867, but not after. Since then, presidential impeachment has required proof of an actual crime. Not just any crime, mind you, but there must be a crime.

High Crimes and Misdemeanors

In applying this opaque term, which derives from contradictory English legal precedents dating back to medieval times, early American impeachments did not require a crime to justify removal from office.

Before 1867, the House of Representatives impeached four judges, two of whom were removed from office after Senate trials. The Senate voted unanimously to remove West Humphreys of Tennessee, who was serving as a judge in the Confederate government and inciting rebellion against the United States. John Pickering of New Hampshire lost his position for erratic conduct that convinced the Senate he was unfit for office.

The Senate declined to remove from office two early judges who were impeached by the House. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase was charged with making intemperate harangues from the bench, while Missouri District Judge James Peck allegedly abused his power to hold lawyers in contempt of court.

Three of those impeachments – all but the one involving Humphreys, the Confederate judge – did not involve any alleged crime. Neither did the 1843 resolution to impeach President John Tyler, which the House rejected by a 2-1 margin.

Based on those precedents, Republicans who longed to drive Andrew Johnson from the White House in 1867 saw no need to charge him with crimes. Instead, they accused him of abusing his office by restoring ex-Confederates to political power after the Civil War, “their hands still red with the blood of our people.”

The impeachers added a grabbag of other complaints, including returning confiscated lands to pardoned rebels, corrupting the nation’s tax service, and inciting an 1866 slaughter of black and Republican activists in New Orleans.

Opposing the impeachment effort, Congressman James Wilson of Iowa, Republican chair of the House Judiciary Committee, objected that no crime was alleged. It was a weak constitutional argument, since American impeachments had not required the showing of a crime until then. But it proved a powerful political argument. Did the impeachers, Wilson asked, define an impeachable offense as “the doing of something that that the dominant party in the country does not like?” Would they support that standard if Democrats controlled Congress and could bring impeachments?

“If we cannot state upon paper a specific crime,” Wilson insisted, “how are we to carry this case to the Senate for trial?”

The impeachment resolution failed, 57 to 106. Even a majority of Republicans voted against it.

Eleven weeks later, after President Johnson had fired Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, the House impeachers showed they had learned their lesson. Eleven new impeachment articles repeatedly accused Johnson of violating the Tenure of Office Act, a law that specified that any violation of it was a “high crime and misdemeanor.”

The House overwhelmingly approved those impeachment articles. After a four-week trial in spring 1868, the Senate acquitted Johnson by a single vote.

Show me the crime

Later impeachers also learned the lesson of December 7, 1867. Impeachment articles against Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton carefully included charges of specific crimes: obstruction of justice with Nixon, perjury with Clinton.

The lesson is straightforward. Impeachment is a political act masquerading as a judicial proceeding. The process involves the decapitation of one branch of government by a rival branch. It should be difficult, not streamlined. The standard should be clear, not flexible and subjective.

To face the voters after exercising such ultimate power, congressmen and senators have insisted for a century and a half that they must be able to point to a crime. A specific crime. They always will.

From the Clinton impeachment we also learned that not any crime will do. President Clinton’s testimony about his sexual imbroglio was plainly false, yet because the senators of his political party did not think that crime warranted removal from office, he won acquittal.

Thus, charging that a crime was committed is necessary, though not sufficient, for presidential impeachment. The words written by Chairman Wilson a century and a half ago still resonate: “Political unfitness and incapacity must be tried at the ballot box, not in the high court of impeachment.”