History is Beyond the Relentless News Cycle

We measure time by generations, are shaped by when we were born, are carried by the currents that take us, without consultation. The news, which is coming at us so fast these days, is relentless. It’s worth stepping back to find our bearings if we can.

When my father was born in 1936, men and women who had been slaves were still walking around New York City. The wave of immigrants that came by boat to Ellis Island were living in thickly settled neighborhoods, relying on kinsmen, on ethnic associations, on religious institutions, with one foot in “The Old World.” In those days, veterans of That War To End All Wars still woke up with nightmares. When my father was a child, the United States was in the midst of the Great Depression. And then there was the drum beat of fascism, followed by death and devastation on a massive global scale. My father remembered his mother crying on the day that FDR died. He remembered her collecting money to help the Jewish refugees of Europe. He remembered her going from office to office in search of lost family members that she and her husband, my grandfather, had left behind.

My father remembered the creation of the state of Israel as if it were miracle—new life emerging out of rubble and tears. He was a young man in the years of unprecedented American economic growth that followed World War Two. He ended up with far more than he ever expected. He took pride in what he was able to give us, even as he worried that my brother and I grew up expecting too much. “Your asses,” he used to say “are sitting in a tub of butter.”

My father served as an American soldier in a largely segregated army stationed in North Carolina. As a college professor at Hunter College in New York, he lovingly taught students of all colors, and many new immigrants, often the first in their families to go to college, who looked at him as an old American, an old white guy.

I grew up in those last days of the Cold War. In elementary school we watched a movie about nuclear annihilation. I remember the black and orange signs for bomb shelters. Years later on television I watched the Berlin Wall fall down. I remember the euphoria of the early 1990s—the disintegration of the Soviet Union and collapse of the Communist bloc, how the Internet emerged into our everyday lives, how postmodernism raged on college campuses, how Francis Fukuyama’s book, The End of History, embodied the zeitgeist, how, even though society was changing, there were figures and forums with wider authority, relative respect and decorum across political differences, and a slower pace to the news cycle that allowed, compared with today’s relentless tribal frenzy, time to digest.

In the early 2000’s, I lived in Yerevan, Armenia, the former Soviet Republic, where I experienced a society in radical tumult, old people disoriented, factories closed down, borders opened, other borders newly shut off, young people impatient, primordial hatreds reemerging along with new opportunities, a growing range of consumer choices and models of what to want. On the outskirts of Yerevan, Armenia, I witnessed countless unfinished apartment blocks, started under the Soviet Regime and then spontaneously abandoned, with shells of buildings left to decay. Everywhere, the remnants of Russian power were in retreat, while American power was dominant as never before.

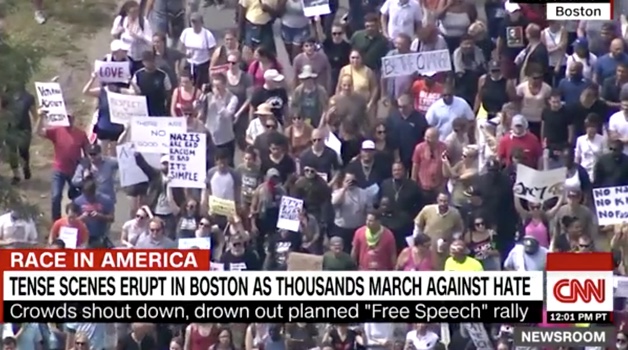

I was in Yerevan, Armenia, when my brother, on his way to the CUNY Graduate Center, saw the second plane go into the World Trade Center. And now, in 2018, figures as diverse as Madeleine Albright and Emmanuel Macron warn about the rise of fascism. We read about the refugees and immigrants on the march, the nativist reactions across the board, the faltering of the European project. We read about how memories of the Holocaust are receding. We read about the retreat of America from the post-war world that it created. We read about the relative decline of American influence, how the Russians are disrupting all that they can, while the Chinese flex their muscles on the world stage under one-party rule, while in Israel and Palestine, the status quo festers like a rancid sore.

When I was growing up, we watched network television. At a certain point, we got a remote control. Our favorite shows appeared at scheduled times. A phone was only a phone, which was attached to the wall.

When I got lost on a recent afternoon navigating the Berlin subway system, I asked an elderly man, dressed in an immaculately tailored dark suit, for directions. We took the train together and started to talk. He told me that, while most of Berlin’s metro system was built in the 1920s, the route we were taking had been built in the late 1930s, under The Third Reich. He remembered the war. As we approached my stop and said our goodbyes, he looked at me and said: “Those were terrible years; those were terrible years.”

Until he died in May of 2017, my father was filled with unabashed love and gratitude for America, with love and deep ambivalence for Israel, with concern for what the future had in store. He cursed the terrorists who attacked what he considered to be his city on 9/11. He believed that the New Deal had saved capitalism but that the capitalists were too greedy and had not learned the relevant lessons. He worried that he had lived during a specific window of time that was closing. He believed that American institutions were stronger than Donald Trump and his minions. He looked forward to hard copies of The New York Times arriving each morning at his door.

In the midst of the relentless news cycle, as we are carried by currents beyond immediate understanding, I suggest that we talk with our older loved ones among us, that we exercise our historical imaginations to gain a sense of where we are coming from and how we might best navigate between the cliffs, rocks and storms that threaten to destroy what we cherish. This is our moment, those of us living, to shape what exists for future generations, to have a hand in what the world will be after we, too, are gone.