The Inaccurate and Dangerous Premise of the GOP Farm Bill

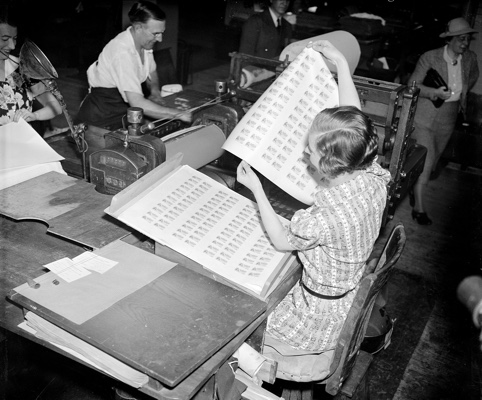

The first printing of food stamps. Washington, D.C., April 20, 1939.

As Congress debates the 2018 Farm Bill, a major priority for some Republicans has been changes to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), often still called food stamps. In particular there has been a push for stricter work requirements, mirroring welfare reform efforts from the 1990s. The amendment for stricter work requirements would put a time limit on how long SNAP clients could substitute job training for work, broaden the age range of those required to perform work for food assistance, and punish those unable to meet the work requirements by kicking them off SNAP for up to a year. Representative Mike Conaway, a Republican from Texas and the House Agricultural Chair, proposed these stricter requirements based in the belief that SNAP users now “hop between training assignments” to avoid work. Conaway emphasized that he meant no disrespect to SNAP users, and instead wanted to promote “the dignity that comes from work and the promise of a better life that a job brings.” Support for the bill is currently split sharply along partisan lines, mainly as a result of the work requirements.

What is clear in these arguments is a major attempt to frame the aims of SNAP not as nutrition assistance or social welfare, but instead as a work program. While work requirements for social welfare are not new, the strengthening of work requirements and the paternalistic rhetoric about the importance of work fit into a longer narrative of framing food stamp recipients as undeserving of aid and as not “really” hungry.

What is clear in these arguments is a major attempt to frame the aims of SNAP not as nutrition assistance or social welfare, but instead as a work program. While work requirements for social welfare are not new, the strengthening of work requirements and the paternalistic rhetoric about the importance of work fit into a longer narrative of framing food stamp recipients as undeserving of aid and as not “really” hungry.

The Food Stamp Program that provided the basis for SNAP was formalized in 1964. Although the program marked important food relief for some Americans, there were many problems with the program that kept it from fully meeting low-income Americans’ nutrition needs, including minimum purchase requirements, limits on food choices, and the power of states to determine who should have access to the program. Some white Southern conservatives, for instance, were accused of withholding aid as retaliation for the successes of the Civil Rights Movement, taking particular aim at black citizens who dared register to vote.

Withholding aid was a way of keeping social hierarchies in order, and as NAACP lawyer Marian Wright testified, the inaccessibility of food stamps in Mississippi was “part of an overall State policy to not respond [to hunger] … in order to force these Negroes out.” It was also a way of ensuring cheap, desperate laborers who would be available for seasonal agricultural labor– a history that echoes uncomfortably in the light of SNAP work requirements.

The end of the 1960s, though, marked the so-called “discovery of hunger” in the United States, through Robert Kennedy’s tour of Mississippipoverty and primetime specials like Hunger in America.When conservative Southern Democrats were challenged on practices like withholding food aid in accordance with agricultural needs, though, they often simply challenged the premise that Americans were hungry. To make this challenge, some invoked the specter of the overweight poor person, trying to convey both that low-income Americans had access to enough food and that, if they needed any state intervention at all, they needed intervention in how to use their money. In most cases, the image of the overweight black American was meant to bolster the idea that the American state should get out of the food welfare business.

AfterHunger in America aired, many Americans wrote to the United States Department of Agriculture about what they had seen. Some argued that the documentary illustrated the need for far better food programs. But others simply refused to believe that Americans could be so hungry. One womandescribed the whole situationas the “poverty hoax,” arguing that “if the tax-payer is gullible enough to swallow such nonsense that 10 million people is on starvation in this country, then it is tragic.” “The people he showed looked well and healthy to me,” another wrote. Mississippi Governor Paul B. Johnson rebutted the claim that they were mismanaging food stampsby pointing at black women’s bodies. He explained: “Nobody is starving in Mississippi. The nigra women I see are so fat they shine.” Some northern liberals were also skeptical about widespread hunger. How could there be people so poor they could not buy any food, Secretary of Agriculture Orville Freeman reportedly asked: “How would they exist?”

At the heart of this controversy was skepticism about how trulyhungry low-income Americans were, with their embodied pain and suffering standing in for their deservingness for aid. If they were not visibly dying of starvation (never mind that some actually were), then did they deserve social welfare benefits? One doctor writingto the House Committee on Agriculture explained that “I know a great many people … who are … monstrously obese from a lifetime on ‘commodities’ which tend to be pretty heavy on the starch and fat content.” While activists on the left made similar points to argue for higher quality commodities, this man interpreted his evidence differently. High-calorie commodities were an appropriate foodstuff, he explained, “as it enables a man to put in a good hard twelve hours in the sun on a handle of a hoe or shovel.” It is the lack of laboring, the man’s claim that welfare recipients were “just sitting around waiting for his next welfare check” and therefore “unable to work it off as fast as he takes it in” that was to blame. Laziness, poverty, and body problems were quickly rolled into one. The coded discussion of all these problems rested on the idea of personal economic responsibility.

The discussion of obesity has not been at the forefront of SNAP fights this year – at least not yet – but it has shapedthe discussionenoughin the last decade to provide subtext. Meanwhile, the language of work requirements and the dignity of work invokes ideas of low-income Americans’ laziness while also emphasizing the lack of concern about actual hunger. Ending hunger is not even a discussion amid the new requirements, which take as a starting point the idea Americans can find adequate subsistence and that SNAP is essentially a luxury for the poor instead of a necessity; that if people are not visibly dying of starvation then you should make them work harder. This idea is both inaccurateand dangerous, and yet it remains a premise for the farm bill debate right now.