The Opioid Addiction Epidemic Is an 8 on the Richter Scale

Related Link America’s 150-Year Opioid Epidemic by Clinton Lawson

Of late journalists have been asking me about the history of narcotic addiction in America, the subject of Dark Paradise and Addicts Who Survived. Here is what I tell them, and what I tell anyone looking for a brief, then-and-now introduction.

Prior to the current epidemic of opioid addiction, the United States experienced three historically significant epidemics of opiate addiction. They were historically significant because each shaped, in different ways, public opinion and public policy. They were epidemics because each entailed an unexpectedly rapid increase in the number of new addicts. And they were opiate-based epidemics because that was the adjective then used for opium-based drugs.

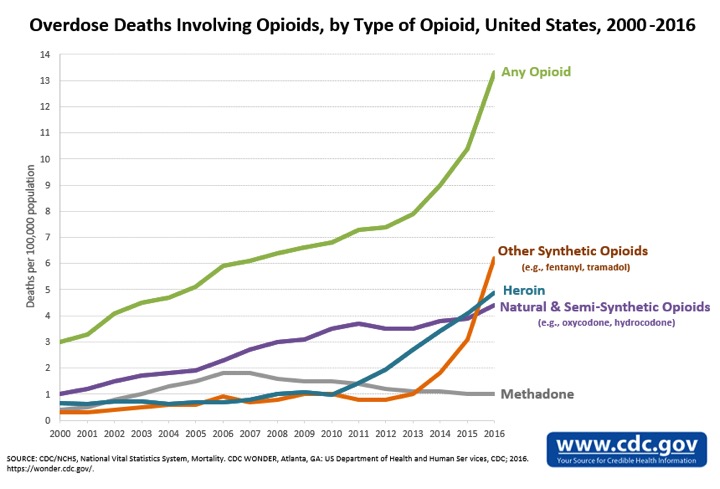

The first of the three opiate addiction epidemics involved opium and morphine. It began in the early 1870s and peaked in the mid-1890s. A second, which involved heroin, occurred in the late 1940s and early 1950s. A third and larger heroin epidemic occurred in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the number of U.S. addicts ballooned to around 600,000. If the late-1940s heroin epidemic had been an earthquake, it would have registered a 6 on the Richter scale: strong shaking with localized damage. The late-1960s epidemic would have been a 7: major destruction with aftershocks. The current opioid addiction epidemic is an 8: widespread, catastrophic, and followed by an overdose tsunami.

Moderate or severe, neither of the mid-twentieth century heroin addiction epidemics originated in medical practice. The first epidemic, by contrast, originated in both medical and non-medical usage. The primary non-medical source was opium smoking by Chinese immigrants, a practice that spread to the white underworld during the 1870s and 1880s. The medical driver of the first epidemic was the growing use of hypodermic medication by American physicians, another conspicuous trend of the 1870s and 1880s. Patients also became addicted through self-medication with patent medicines, laudanum, or other narcotic remedies. But the most prolific source of medical addiction was the hypodermic administration of morphine, typically initiated by a physician.

The likelihood of morphine addiction increased if the physician or patient continued injections during the course of an extended and painful illness. The adolescent girl with pelvic cellulitis. The drinker too fond of the needle for curing hangovers. The doctor with facial neuralgia and morphine conveniently at hand. These were the types of cases that dotted nineteenth-century medical journals.

The case histories came with admonitions. In 1889 Dr. James F.A. Adams reminded his colleagues of three basic truths. Opiates were toxic. They had nasty side effects. And they often led to addiction. Adams judged that 150,000 Americans had fallen victim to addiction, not counting the opium smokers. The best way to prevent more addicts was to use newer, non-opiate analgesics and hypnotics to treat the symptoms that motivated patients to seek out medical care.

Over the next twenty years Adams’s implicit criticism—that doctors who unthinkingly resorted to opiates to treat chronic pain were behind the times—found increasingly explicit expression in journal articles and medical-school instruction. Progressive doctors and pharmacists lobbied for local and state laws to control narcotic sales. The most basic measure, adopted by almost every state, was to require a prescription from a licensed physician for legal purchase. Unscrupulous suppliers who dodged these laws faced professional ostracism. “Dope” doctors and pharmacists were shunned. The combination of pressure within the professions and the exercise of state police power without made a measurable difference. Per capita consumption of medicinal opiates fell for 20 years, and cocaine for 10 years, before the Harrison Act—the best-known federal narcotic law of the Progressive Era—took effect in 1915.

Prevention worked. Physicians and pharmacists created fewer new addicts as existing addicts quit or succumbed to age, illness, or overdose. The decline in prevalence had a demographic tailwind, at least for medical addicts who were sicker and older than the younger “pleasure users” who occupied an increasingly conspicuous place in the American narcotic landscape.

When I tell journalists the story of the waning of the first epidemic of medical opiate addiction, they invariably ask me if it makes me optimistic about the current opioid crisis. The answer is yes, but guardedly so. The most obvious historical parallels are positive. Medical professionals were educable. Prescribing patterns were malleable. Legislators were able to impose supply controls. The epidemic was self-limiting, once preventive measures kicked in. The same points still apply. Should the current administration achieve its stated objective of slashing opioid prescriptions by one-third over the next three years, the number of addicts and overdose deaths would begin to decline.

But would addiction decline as quickly as in the past? This is where the “guarded” comes in. The addiction epidemic that began in the mid-1990s also differs in important respects from the one that peaked in the mid-1890s. The opioid crisis is bigger and more diverse. It is fed by more, and more powerful, drugs. Semisynthetic drugs like oxycodone are more potent than opium and morphine. Synthetics like fentanyl are much more potent and liable to cause overdose, to the point that police dogs sniffing out traces of the drug succumb.

There are social differences, too. The opioid addiction epidemic has occurred in a climate of growing permissiveness, falling economic expectations, accelerating family decline, and rising neoliberalism. The devil-take-the-hindmost spirit has been particularly evident in the pharmaceutical industry, which has become notorious for slanting drug research and corrupting medical practice. As bad as things were in the 1870s and 1880s, there was no opium- or morphine-hustling equivalent of Purdue Pharma showering doctors with meals and conference trips and company-backed research proclaiming Oxycontin to be safe for long-term use and a godsend for long-suffering pain patients.

Finally, Victorian addicts did not have as many alternative sources of supply. Illicit drug dealers, whom medical addicts scorned anyway, mostly operated in Chinatowns and big-city tenderloins. No Mexican cartel hirelings in beater cars drove around Midwestern towns with balloons of cut-rate heroin stuffed in their mouths. In the early twentieth-century, the licit narcotic supply was national, but the illicit supply was local and concentrated in the bicoastal urban underworld. As late as the 1950s, jazz bookers avoided sending addicted musicians to heartland cities and towns where heroin was no more than a rumor. Now the police in those same cities and towns carry Naloxone overdose kits. By the early twentieth-first century both licit and illicit opioids had become nationally available, not to say aggressively promoted—the primary reason we got into the current fix.