Which of the GOP Leaders in Congress Will Be Remembered for Their Moral Authority?

“History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes,” Mark Twain was reported to have said. I have been thinking about that observation as the minuet between Donald Trump and the Republican Party continues. While Trump undermines the rule of law in an attempt to protect his presidency from the Mueller investigation, his party members swirl around him, some of whom challenge his actions, others attempt just to survive, while still others are willing accomplices. In researching the emergence of the abolitionists movement in the 1830’s, I was struck by the similarity in the way politicians of that era lined up in reaction to the great moral question of their era: slavery. In this regard, perhaps Karl Marx was right that “history repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce.”

As has been well documented, Andrew Jackson is Donald Trump’s favorite president. Jackson’s response to the abolitionist movement of his day parallels Trump’s reaction to the events in Charlottesville, Virginia in 2017. As Franklin Delano Roosevelt famously said, the presidency “is preeminently a place of moral leadership.” If so, not only did Trump fail the test of moral leadership, but so did Jackson, who considered abolitionists “an evil force dedicated to the dismemberment of the Union and the discrediting of the democracy,” as his biographer Robert Remini has written.

When abolitionists flooded the South with anti-slavery tracts in 1835, Jackson proposed legislation to Congress that would ban the distribution of abolition materials, a proposal which was never adopted. Jackson, who owned one hundred and fifty slaves, could be a harsh slave owner, once posting a reward for the return of a fugitive slave that offered an additional “ten dollars for every hundred lashes” laid on him. Jon Meacham writes that Jackson was “blinded by prejudice of his age, and could not see … that the promise of the Founding, that all men are created equal, extended to all.”

Jackson’s old rival, John Quincy Adams, stood on the other side of the slavery issue. I equate his position with that of John McCain, who has continued to be a thorn in Trump’s side, despite fighting a brain tumor. In his recently released book The Restless Waive, McCain writes: “I’m not sure what to make of President Trump’s convictions. His lack of empathy for refugees … is disturbing,” while at the same time Trump compliments “some of the worst tyrants.”

Although Adams was no supporter of the immediate abolition of slavery and considered men like William Lloyd Garrison to be “fanatics,” his sympathies clearly lay with those who wanted to gradually emancipate the slaves. “His parents, and especially his mother, Abigail, had passed along to him their antislavery views,” the historian Sean Willentz has written. During his time serving in the Monroe administration, he had discussed slavery with John Calhoun, and came to the conclusion that “if the Union must be dissolved, slavery is precisely the question upon which it ought to break.” Yet always the strong nationalist and unionist, he attempted to put that day off, supporting the Missouri Compromise.

A former president, Adams was dragged into the slavery debate as a member of Congress when the abolitionists began to bombard that body with anti-slavery petitions in the aftermath of their failure with mass mailings in the South in late 1835. A proposal was made that such petitions be accepted but then tabled from further discussion. This was too much for Adams, since it violated “the Constitution of the United States, the rules of this House, and the rights of my constituents” to petition the Congress. During the debate on the bill, he asked the bill’s opponents “Am I gagged or not?” when they tried to silence him. Even though the resolution passed in the House, Adams continued to challenge what became known as the gag rule, so named for his outburst on the House floor. Adams would rise day in and day out to present some new abolitionists’ petition. While the gag rule was designed by southerner slave holders to eliminate discussions about the “peculiar institution,” it actually fostered them.

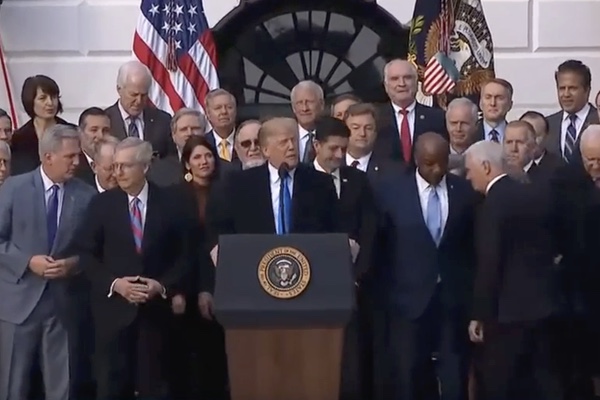

Martin Van Buren’s actions on abolitionism were distinctly different from Adams. I see a link between Van Buren and both Speaker of the House Paul Ryan and the Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnel. Both have attempted to act in a pragmatic manner toward Trump, tolerating parts of his behavior in order to achieve some of their long-held policy goals. As McConnel said, 2017 was “the most consequential year” of his tenure in the nation’s capital. But cooperating with Trump has cost Ryan and McConnel a part of their reputation, and one must wonder how much of Ryan’s decision to retire from Congress was due to dealings with Donald Trump.

Van Buren, like Ryan and McConnel, dealt with the issue of abolitionism from a largely pragmatic position. Since he was running to replace Jackson on the Democratic ticket in 1836, he needed to hold together Jackson’s coalition of southern slave owners and northern Democrats, or what remained of them in the aftermath of the Nullification Crisis and the bank wars. Van Buren was also the first of a new breed of politicians that saw political parties and the competition for office as natural in a democracy. “Tolerating agitation over slavery would destroy the nation’s political fabric,” Willentz writes, and so Van Buren joined with Henry Clay and Jackson in attempting to keep slavery off the political agenda.

Van Buren worked to suppress the distribution of abolitionist materials during the mail controversy and he supported the gag rule in Congress. He wrote to one friend that slave owners were “sincere friends to mankind,” while abolitionists were out to undermine the Republic. His actions were sufficient to gain him the presidency when the Whigs ran three regional candidates against him. During his Inaugural Address, Van Buren promised not to interfere with slavery or to support the movement to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia. Yet “despite all he did to shore up his Southern credentials, there was always a lurking fear among Southerners that Van Buren was secretly anti-slavery,” his biographer Ted Widmer writes. Van Buren failed to gain reelection in 1840, largely due to two economic panics. By 1848, he would support a ban on slavery in the territory obtained during the Mexican-American War and run for president as part of the Free Soil Party, a precursor to the Republican Party.

In the Trump orbit, there are also true believers. I put Representative Devan Nunes in that category, and equate him with Senator John Calhoun, who not only opposed abolitionism, but made the case that slavery was a positive good. Some have argued that Nunes may be supporting Trump out of self-interest. While it is certainly true that Nunes has generated substantial campaign contributions from Trump supporters nationwide, he was also an early supporter of Trump in 2016. We can never be certain of the motivations of any individual, but it does appear that Nunes is a true believer.

Calhoun was at the far extreme of American politics in the 1830’s. Unlike his fellow Southerner, Thomas Jefferson, Calhoun did not view slavery as “a necessary but temporary evil,” as Richard Hofstadter has written. Nor did he share John Quincy Adams’s view of the equality of all human beings, since in the South this only applied to white men. As he said in the Senate in 1837, slavery “is, instead of an evil, a good, a positive good.” Calhoun supported Jackson’s efforts to stop the spread of abolitionists’ mail, although his fear of a strong central government led him to recommend that this be done pursuant to state laws. He also supported the gag rule.

Of the three men, Adams, Van Buren and Calhoun, only one survived the antebellum period with his reputation largely intact on the defining moral issue of their time, although Van Buren attempted to make amends. One must wonder, when future historians write of our era, whether it will be McCain, Ryan, McConnel or Nunes who will be considered a person with moral authority. The answer seems obvious.