What Donald Trump doesn’t know about the War of 1812

President Donald Trump has defended his position that protective trade measures against Canada are necessary for reasons of national security and, in a phone call with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau leading up to what became a contentious G7 meeting in Quebec, told his Canadian counterpart: “Didn’t you guys burn down the White House?”

After details of the May 25 phone call were leaked, the War of 1812 was actually trending on social media. I was oddly giddy. Millions of dollars spent for bicentennial celebrations in Canada in 2012 had been incapable of achieving such attention for this little-understood war.

The trouble is, the attention hasn’t been (for the most part) paid to the things historians like me consider significant. Instead, the incident has become yet another opportunity to lambaste Trump’s depressing lack of historical knowledge.

For the record: the White House was burned by British Redcoats, not by Canadians. And as subjects of the British Empire, “Canadians” were, in a way, “British.” But Canadian militiamen were quite distinct from the scarlet-coated Regulars of His Majesty’s Army. The building wasn’t entirely burned down, either. Nor did it get the name “The White House” because it had to be painted to cover the humiliating scorch marks.

I frequently make these corrections. I did it again in the wake of Trump’s impressively nonsensical defence of escalating economic warfare. In fact, I make corrections on such a regular basis that you might begin to think the only thing of interest that happened between 1812 and 1815 was the burning of the White House. At least, that’s the impression that came from talking to Canadians before Trump’s comment.

A good Canadian story

Normally, the first thing many people say to me when the subject of the War of 1812 comes up is something like: “Ooh, we burned down the White House in that one, eh?”

The “we didn’t do it” arguments Canadians are now making about the burning of the White House are therefore a little unexpected. What we once loved to own, told back to us by a man we love to hate, is suddenly deeply insulting.

In Canadian hands, the burning of the White House was a heroic, David-and-Goliath tale. It’s about plucky young lads seeking a justified revenge on the arrogant American colossus — a familiar and comforting narrative for many Canadians. Yet from the mouth of the U.S. president, it’s a gross historical inaccuracy and an insult to our apparently peace-loving natures.

The truth of the events are unlikely to resolve this particular contradiction, but they are nevertheless important for reminding us why the War of 1812 really matters. They’re equally useful for understanding why Trump’s evocation of the destruction of his current residence can be simultaneously silly, anachronistic, inaccurate … yet, understandable.

War comes to Washington

The British forces in the Chesapeake area in 1812-15 were conducting a campaign that looked a bit like an end-run in a football game. For much of the war, most of the action was happening further north, along the shores of the St. Lawrence River and on the Great Lakes.

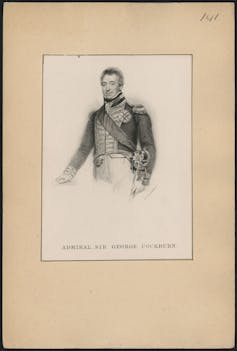

A few keen British officers — Admiral Alexander Cochrane, Major General Robert Ross and the fiery Rear Admiral George Cockburn — had the idea that moving into Baltimore and sacking Washington might be tactically useful. The idea also held the promise of delivering a bit of a smack-down to a bunch of upstart former colonists who’d had the temerity to tell the British Empire that (among other things) they couldn’t kidnap American sailors to man their ships against Napoleon.

The attack on Washington on Aug. 24, 1814, was also vengeful. American soldiers were quite skilled plunderers, not only at the Canadian capital of York (now Toronto), but also in places like Dover and St. David’s.

(Some might also claim the sacking of Newark, now known as Niagara-on-the-Lake, as part of this list of American atrocities. The town was razed completely in December 1813 and the residents were turned out into the cold when all but three buildings in the town were reduced to ashes. However, the plucky lads who burned the town, under the orders of the American General George McClure, were known as the “Canadian Volunteers” — men of Upper Canada who were fighting with the Americans.)

Plunderers, but not killers

Plunderers in the War of 1812, no matter the uniform, attempted to conduct their sackings without indiscriminately slaughtering civilians or stealing private property.

Some of the time, they succeeded in this “civilized” method of combat. When the Americans arrived at York, for example, they focused on public buildings and, in a few notable instances, stopped Canadians from looting each other.

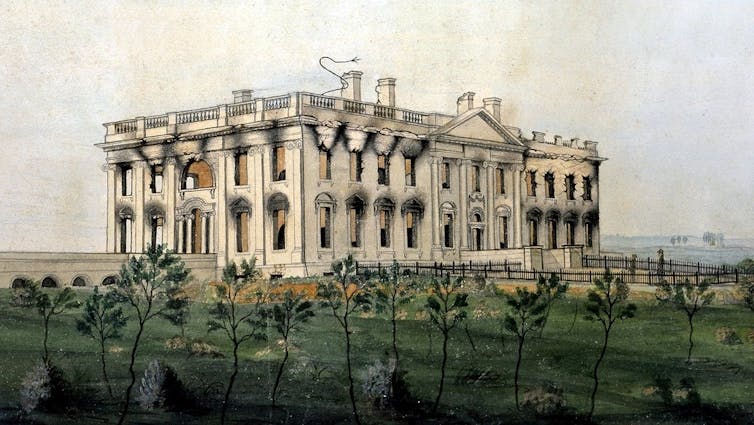

In Washington, many inhabitants described the British invaders as polite. They tried to avoid burning civilian homes, apparently paid for the food and drink they required — but they spared no matches in the destruction of public buildings and, in one instance, the office of a newspaperman who’d been particularly vicious in his portrayal of Cockburn.

All told, there was only a single fatality in the attack on Washington, and about half a dozen injuries. The architectural victims, like the Capitol building and the White House, however, were conspicuous casualties.

Dolley Madison, the fearsome First Lady, had already carted off most of the valuables from the White House (including the now-famous portrait of George Washington), minimizing the cultural damage.

Little advantage

The destruction of Washington provided little tactical advantage to the British, beyond scattering an already divided and bickering group of American politicians. Most officials, including Dolley’s hapless husband James Madison, ran away from the city in a panic as British troops marched toward them.

The pitiful image of bewigged American politicians scrambling away from the city with their coattails flapping is accentuated by the fact that when the British officers and their men arrived at the White House, they found the dining room table set for dinner. The food was prepared and excellent wine waited to be poured. The Americans had apparently been expecting to celebrate a victory that night, but it was instead consumed by their enemies.

However, because the British commanders then ordered the destruction of the White House — a place that, as historian Nicole Eustace reminds us, was not simply a political building but a domestic space — they made it easy for furious Americans to paint the British as disgraceful barbarians.

Within only a few months of the burning of Washington, the Treaty of Ghent was signed on Dec. 24, 1814. The war ended the following February when both governments ratified the treaty.

In the aftermath, Americans did a spectacular job turning a 32-month mess of a war they barely managed to survive (and did not win) into a triumphant victory of manly American prowess.

A war with no winner

While the Americans didn’t win the War of 1812, I’ve never been overly keen to declare Britain/Canada the victor. However, the case can be made: none of the original war aims declared by the Americans were achieved. Canada lost no territory and the treaty ending the war declared everything would be status quo ante bellum. Canada had been effectively defended from the invaders.

When it was all over, the War of 1812 gave Canada and the United States their shared border. The war defined it and marked it on the map in a way that had been fairly easy to ignore before.

It turned former friends and neighbours into enemies. It made Canadian settlers deeply suspicious of American motives on the continent (and it didn’t quell American desire to possess Canadian territory, either).

After all — a point Trump either didn’t know or blithely ignored — the Americans started the war: they invaded first and, regardless of how morally dubious this kind of international tit-for-tat actually is, they invited retaliation.

![]() While Trump got a few of the facts wrong, he’s not the only one. If there’s one thing this entire, silly episode confirms for me, it’s that our history — our collective, complicated, terrible and rarely triumphant history — needs to trend more often, but with far more thoughtfulness and — dare I suggest it? — reading.

While Trump got a few of the facts wrong, he’s not the only one. If there’s one thing this entire, silly episode confirms for me, it’s that our history — our collective, complicated, terrible and rarely triumphant history — needs to trend more often, but with far more thoughtfulness and — dare I suggest it? — reading.