How Thomas Jefferson Illuminates the Politics of Race

In their book How Democracies Die, the political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt write that “the norms sustaining our political system [have] rested, to a considerable degree, on racial exclusion,” pointing to the Compromise of 1877 that led the North to end Reconstruction and leave the South. In the aftermath, the South implemented a whole series of Jim Crow laws that stripped African-Americans of their rights. The political rapprochement Levitsky and Ziblatt describe between Democrats and Republicans seemed to hold until the civil rights movements of the 1960’s. That American politics only works well when racial minorities are excluded is chilling to contemplate, especially in this age of Donald Trump, when racial politics have once again come to the forefront in the aftermath of the events at Charlottesville last summer and the president’s continuing attempts to divide people along racial lines.

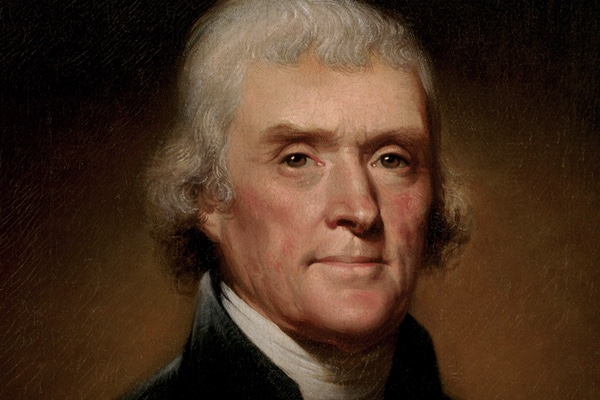

Perhaps part of our problem with race in America is an unwillingness to confront the past. The headline for the August 9, 2018 Time Magazine article reads “Spike Lee Wants BlacKkKlansman to Wake America Up.” In the article, the writer indicates how Lee’s intent in making a movie about a black cop who in the 1970’s infiltrates the KKK is to educate us about the history of slavery and racial discrimination in America. The civil rights attorney Bryan Stevenson has recently opened the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, devoted to the victims of lynching. As Stevenson told Time, “we can’t ignore this part of our history that we have been so reluctant to address if we want to be seen as we truly are.” Both Lee and Stevenson point to the fact that we will be unable to heal the racial divide in America until we confront our own history, a history of black enslavement followed by black exclusion. In this spirit, it may be helpful to look at the life of Thomas Jefferson.

Perhaps part of our problem with race in America is an unwillingness to confront the past. The headline for the August 9, 2018 Time Magazine article reads “Spike Lee Wants BlacKkKlansman to Wake America Up.” In the article, the writer indicates how Lee’s intent in making a movie about a black cop who in the 1970’s infiltrates the KKK is to educate us about the history of slavery and racial discrimination in America. The civil rights attorney Bryan Stevenson has recently opened the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, devoted to the victims of lynching. As Stevenson told Time, “we can’t ignore this part of our history that we have been so reluctant to address if we want to be seen as we truly are.” Both Lee and Stevenson point to the fact that we will be unable to heal the racial divide in America until we confront our own history, a history of black enslavement followed by black exclusion. In this spirit, it may be helpful to look at the life of Thomas Jefferson.

No American of the early Republic so reflected the ambivalent view of slavery and injustice towards African-Americans as Thomas Jefferson. On the one side, Jefferson put forward the America that we think of as exceptional. In the natural rights section of the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson espoused the universal ideas of liberty, equality, self-government, and the freedom to pursue one’s own happiness. This would ultimately become the American Creed, what Jefferson referred to in 1776 as an expression of the “American Mind.” He was the major proponent for the role of the common man in politics, which led to the growth of democracy in America. Jefferson stood for equality (at least for white men) and feared that the concentration of wealth would destroy self-government. Those ideas helped to give birth to a new nation that was conceived as an idea, not a collection of people defined solely by race or ethnicity.

The ideas that animated our founding were aspirational, not the reality of the world that Jefferson lived in. Even today we continue to struggle to ensure that all people are treated equally and are free to pursue happiness. Barack Obama may have expressed it best in 2008 when he said that race “is a part of our union that we have not yet made perfect.” Decades earlier, Martin Luther King, Jr. eloquently proclaimed from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in 1963, “When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were giving a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir…instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the negro people a bad check….” As King reminds us, our founding documents did not apply to blacks, women, and Indians at the time that they were written, nor did they apply at the time he spoke in the middle of the 20th century. But once written, they can and have been claimed by many who say yes, I too can be equal and free. Much of American history has been the story of the excluded claiming their rights, a struggle that continues to this day. A large part of what makes America exceptional is the ability to change.

Jefferson was inconsistent in his views on slavery. He believed that slavery was evil, yet he owned a large plantation and enslaved African-Americans. He thought that slavery degraded not only those who were forced into it, but also had a deleterious effect on those who owned other human beings. “The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other,” Jefferson wrote in Notes on the State of Virginia. During the early part of his life, he supported a law that would allow Virginia slave owners the choice of emancipating their slaves. He also proposed, as part of the Ordinance of 1784, that slavery be banned from all new territory west of the Appalachian Mountains, a measure that failed by one vote in the Confederation Congress.

Despite writing that “all men are created equal,” Jefferson actually believed that blacks were inferior. “I advance it, therefore, as a suspicion only, that the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of mind and body,” Jefferson wrote inNotes. He also made allowances that the condition of slavery had in fact led “to the degraded condition of their existence,” as he later wrote in 1791.

Jefferson, like many of his contemporaries, thought that a mixing of the races would result in the “staining of the blood of the master.” But Jefferson also engaged in a long-term relationship with one of his slaves, Sally Hemmings, who was his wife’s half-sister. She bore him six children, four of whom survived to adulthood. Jefferson freed all of them when they became adults, yet he failed to free his other slaves while alive nor when he died. Despite having mixed race children, Jefferson never believed that white and black people could live together in a racially heterogenous society, and so he proposed numerous schemes for the colonization of black people somewhere else upon their emancipation.

Jefferson’s view on the elimination of slavery underwent a major evolution over the course of his life. When he was young, he thought it could be accomplished by his generation. Later, he thought the next generation could achieve its elimination. The date when it could occur was continually pushed out, until the growth of the “peculiar institution” began to make its abolition all but impossible by the time of the Missouri Compromise. By then, Jefferson doubted that it could ever occur.

Jefferson largely chose to work behind the scenes, even when he was young, unwilling to take the lead on an issue that was clearly not popular in parts of Virginia and the Deep South. When approached to become a member of an abolition society while in France, he responded that such an association “would be too public a demonstration of my wishes to see it abolished” and “might render me less able to serve it [the pursuit of abolition] beyond the water,” or, in other words, at home.

Jefferson continues to illuminate our racial outlook, only in reverse. While Jefferson became less open to abolishing slavery as he aged, the United States has improved racial relations over time. As Barack Obama said in 2008 in his speech on race, “What we know… is that America can change,” and it has. In my own lifetime, Jim Crow segregation has ended in the South; people of all races can vote; and the doors of opportunity are available to far more women and people of color. We even elected an African-American president. Despite the progress made, we have not yet arrived at a post-racial society, as the election of Donald Trump has made abundantly clear. We still aspire to build that more perfect union, and remembering our history is a good place to start.