Woodward’s Trump Book Gives Us an Opportunity We Shouldn’t Miss

While we’re shouting that the emperor has no clothes, we should also remember that there should be no emperors either.

Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” first published in his 1837 Fairytales for Children, had narrative precedents that went back centuries and across dozens of cultures. No doubt there is something of the elemental about the story, perhaps accounting for the almost omnipresent popularity of the tale. Virtually everyone has heard the idiom that “The emperor has no clothes,” whether they read it in Andersen, the medieval Spanish Tales of Count Lucanor compiled in 1335, or a Hindu source from a century before.

We intuitively know the truths of fairy tales, and the celebrated Andersen parable about a foolish emperor believing that he is parading in special finery visible only to the worthy when in reality he is marching in the nude tells us something crucial about power. It’s meaningful that the subjects in the tale pretend that they can see the monarch’s regalia when in reality he is stark naked. Andersen’s story strips the artifice of power as bare as the pink, wrinkled body of the emperor; the Dane reminds us that power is a fiction that is granted through consensus. But the young boy who innocently shouts the most famous line from the story imparts a wisdom even more crucial, for if power is granted by consensus, the child reminds us that the social contract is always fit for renegotiation.

That our president has no clothes is so manifestly apparent that it’s exhausting to even make the observation. His vainglorious, petty, small-minded, vindictive, cruel, narcissistic personality is so clear that a reader is tempted simply not to believe any of Donald Trump’s defenders who claim that those adjectives don’t apply to him. Pundits, columnists, and journalists not working for the right-wing echo chamber have said as much since before Trump’s campaign began; Democratic politicians have observed this reality about the president, but then so too have Republican representatives, though despite the occasional chiding from Senator Bob Corker or Senator Jeff Flake (who vote the majority of the time with Trump) they rarely seem willing to go on record for it. Among the 65% of us who disapprove of Trump, who’ve been parsing his fact-free, syntactically-creative missives on Twitter, we’ve known for years that this is an emperor whose pink flesh is grotesquely gleaming in the sunlight while he struts down Pennsylvania Avenue with an imaginary crown on his head. Right now, close to three quarters of the crowd are crying out the mantra of “The emperor has no clothes!” The emperor’s band plays on regardless, it seems.

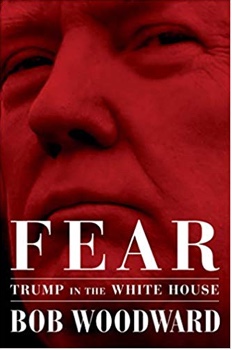

Then of course there are the books like Michael Wolff’s Fire and Fury: inside the Trump White House, former Trump staffer and retired gameshow contestant Omarosa Manigault Newman’s Unhinged: An Insider’s Account of the Trump White House (reviewed hereon HNN), and now the respected Washington Post and Watergate reporter Bob Woodward’s upcoming Fear: Trump in the White House. Such accounts console and disturb us. In reading that the former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson described Trump as a “fucking moron” we can preserve our own sanity regarding our skills of observation. But these anecdotes ultimately prove themselves disturbing, for we learn that the people who work with Trump have reached similar conclusions to the rest of, and yet they still work with him. We can be an audience screaming that “The emperor has no clothes!” and it seems to make no difference.

Woodward’s book, released this coming Tuesday, is the most damning entry, since the White House can neither dismiss the report as the product of a schlock reporter, nor the jilted missives of a former employee. While Trump’s supporters will scarcely care, Woodward’s reputation as the respected investigator who helped bring down the Nixon administration will no doubt ensure the veracity of his claims. It’s become a truism of the Age of Trump that we should learn not to be shocked, and yet there is still something curdling when you read that Chief of Staff John Kelly concludes that the president is an “idiot” or that Secretary of Defense James Mattis places Trump’s intellectual capabilities at around that of “a fifth-or-sixth grader.” Kelly says that “[Trump’s] gone off the rails. We’re in Crazytown. I don’t even know why any of us are here. This is the worst job I’ve ever had,” confirming our suspicions about the president’s pathologies, especially since it’s coming from those with the misfortune of having to work closest with him.

What’s far more horrifying are revelations that staffers have taken to radical solutions, including purposefully confusing the erratic leader so as to avoid his disastrous decisions. Mattis reportedly had to slow-walk Trump’s proposal to assassinate Syrian dictator Basher al-Asaad until the president forgot that he’d suggested it, and former Chief Economic Adviser Gary Cohn actually “stole a letter off of Trump’s desk” to prevent the United States’ formal withdrawal from a trade agreement with South Korea. Mattis, when asked why such actions are taken, responded that “We’re doing this in order to prevent World War III.” Avoiding nuclear Armageddon now apparently hinges on who can hide the proper documents from the president.

If you can still your abject terror long enough, an analysis of the events described by Woodward can offer up some lessons about how power operates – especially in its fictionality. Power is only power insomuch as one can convince a large enough group of people that you are worthy of it. In a democracy that legitimacy should clearly be invested in individuals chosen through election, though in Trump’s case the issue is complicated by his abysmal popular vote totals. That the word “power” refers not to brute physical strength is so obvious that it scarcely seems worth mentioning, though like the boy screaming about the naked emperor, sometimes it’s crucial to note obvious things.

The U.S. government is thankfully not a troop of gorillas, but if it were, Trump would be no silverback. When we think of power – and Trump certainly now has the power to flout constitutional norms, to derail the economy, or to commit us to war – it’s sobering to remember that such authority is invested in a roughly 300 pound, 72-year-old man with a fast food addiction. I make this observation not to say that those facts in and of themselves should necessarily disqualify a theoretical leader, but rather only to emphasize the fictionality that by necessity defines power. Trump is powerful not because he is deeply, essentially, literally powerful, but because enough people have agreed that he should be powerful (for some inscrutable reason).

That fictionality also defines the (welcome) resistance of men like Cohn, for whom hiding a simple piece of paper, materially no different from trash, prevented economic calamity. There is something of magic about the whole thing; we pretend that Trump is powerful, and so he is; we pretend that the paper of treaties can change the world, and so they do; we pretend the emperor has new clothes and we see ermine-trimmed velvet. Woodward’s title derives from a quote of Trump’s, when in a rare moment of astuteness, he observed with Machiavellian gleam that “Real power is … ‘Fear.’ ” The president is correct, that is the oozing substance which adheres his entire regime together.

I’d suggest that the medieval historian Ernst Kantorowicz, author of the classic 1957 study, The King’s Two Bodies, has something to tell us about the interaction of a symbolic office to the person who occupies that office. Kantorowicz argued that medieval and early modern models of sovereignty understood a distinction between the position of the King and of the person who held that position, the “two bodies” of his title. Such is what allows Elizabeth I in 1588 to declare during her triumphant speech to the troops at Tilbury that “I know I have the body of a weak, feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too.” The doctrine of the “King’s Two Bodies” strictly separated the mystical office of the sovereign from whatever fallible human operated within that role, but the later of course was invested with tremendous power by recourse to the former. It’s that which allowed the phrase “The King is dead! Long live the King!” to make any logical sense, but as Kantorowicz writes “Political mysticism in particular is exposed to the danger of losing its spell or becoming quite meaningless when taken out of its native surroundings, its time and space.” Let’s try and lose a little of that spell in our own time and space.

Alone among developed Western democracies the United States endows the elected office of the presidency with a certain regal significance. Great Britain, for whom we supposedly fought a radical revolution to free ourselves of such tyranny, has a Queen of course, but their Prime Minister is another member of Parliament, not the imperial executive which the American presidency has slowly evolved into. In that fight between Thomas Jefferson and John Adams about the stateliness of the office the later has long since won over the former. Our president is no citizen-volunteer. Kantorowicz’s observation about the “King’s Two Bodies” is alive and well in how we discuss the presidency, where the Oval Office and the White House are shrouded in an almost mystical-aura, but where focusing on the fact that Trump is a horrible president can obscure the fact that he’s a horrible person, one who is now clothed in unspeakable power for some reason.

The fact is that a man whom most adults wouldn’t see fit to watch their house while they’re on vacation now has the nuclear codes. Such a development is a product of this irrational adherence to the superstition surrounding his office. The presidency has the stench of monarchism about it. It’s always been undemocratic – it should go. Or at least how we talk about it needs to radically change. I’m not suggesting a constitutional alteration to abolish the office (per se), but I am imploring us to speak of the position without the medieval mysticism that feudalists applied to their kings. Rob Porter, the presidential aide fired for spousal abuse in February, said that Trump’s was “no longer a presidency. This is no longer a White House. This is a man being who he is.” But we forget to our detriment that all presidencies are simply men being whom they are – Trump simply happens to be a particularly horrible man.

Too often the centrist Democrats who compose the bulk of the #Resistance perseverate on the magic and ritual of the presidency as a means of counteracting Trump. Understandable perhaps, but also a pose that leads to irrationalities like the recent valorization of the war criminal George W. Bush. The fact is that even Democratic presidents like Barack Obama, who accomplished much that should be celebrated, did nothing to roll back the inordinate powers of an increasingly imperial presidency. The left’s project cannot simply critique this president, but the presidency.We must progress towards a future where the person occupying the Oval Office is decent, but also to where it matters less whether or not they are. It can be easy to overlook the detriments to such power when the White House is home to a Roosevelt, Kennedy, or Obama, but Trump’s example demonstrates that such power comes with dire risks and hideous costs. We should keep on shouting that the emperor has no clothes, but we should also remember that there should be no emperors either.