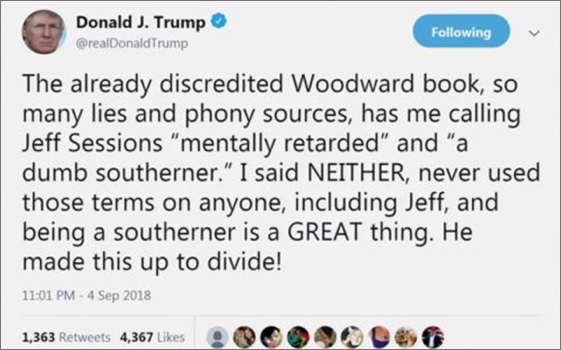

What’s So Familiar About Trump’s Claim that Jeff Sessions Is a “Dumb Southerner”

Of the various revelations to emerge from Bob Woodward’s bestseller, Fear: Trump in the White House, the veteran journalist’s new book about the chaotic current administration, the president’s reported dismissal of Attorney General Jeff Sessions as a “dumb Southerner” and “mentally retarded” in a conversation with then-White House staff secretary Rob Porter is one of the least surprising. More than suggesting the staying power of tired put-downs about the region, by equating southernness with stupidity, these epithets establish Trump, who relies heavily on white southern voters for his support, as part of a long tradition of Americans (typically non-southerners) beating up on the South. And yet the South has been—and remains—more than a favorite punching bag. Throughout US history, another set of attitudes about the southland has competed in the American psyche: one in which the region is envisioned as the guardian of the country’s traditions, its most unaffected and authentic locale.

This love/hate attitude is hardly of recent origin. It is nearly as old as the Republic itself. The 1960s and 1970s, though, were an especially critical moment in imaginings of the South, particularly the white South. That the South’s supposedly positive qualities often outshone its perceived negative characteristics during this period reveals the desperation of Americans to simultaneously make sense of and escape a messy and confusing cultural and political landscape.

Consider the cultural diversity of some of the purveyors of this imagined South of the long sixties. Novelist Harper Lee, segregationist Alabama governor and presidential candidate George Wallace, country-rock artist Linda Ronstadt, and JFK and LBJ presidential aide Richard Goodwin would seem to have little in common at first glance. But during the tumult of the sixties and seventies, these individuals dreamed of the white South as a refuge from America’s problems. What were these problems? They ranged from anomie to suburban malaise to presidential deceit to racial discord to empty consumerism. These diverse and hard-to-solve dilemmas lent Americans a feeling of rootlessness, a regrettable condition explored by pop sociologist Vance Packard in A Nation of Strangers, his 1972 book about the breakdown of the bonds that had traditionally linked Americans together. Certainly, Lee, Ronstadt, Wallace, and Goodwin did not all view the white South in the same way, but they were united in their belief that there was something about the region that could help to rescue their beleaguered, rootless nation from ruin.

For Lee, the Alabama native and To Kill a Mockingbird author, the South was a place that, while suffering from the blot of racism, contained the close-knit sense of community that came from small-town living, as well as forward-thinking whites who might eventually eradicate black-white divisions. Goodwin, a Jewish Bostonian, was similarly hopeful, positing that the South had maintained its rural roots and the human connectedness that he saw dissolving all too quickly around “modern man.” The Arizona-bred Ronstadt, though no ideologue herself, covered classic country tunes, rooted in the traditions of the rural South, frequently for a countercultural audience eager to tap into the alleged authenticity of rural white southern living to bolster hippies’ critiques of the Amerikan technocracy. Like these others, Wallace and his supporters envisioned the white South as an oasis in an environment of unsettling changes, but unlike Lee, Ronstadt, and Goodwin, he embraced a South woven from the interconnected strands of white supremacy, “law and order,” and unapologetic masculinity as a bludgeon for batting down the progressive agendas of feminist, antiwar, and civil rights protesters. The imagined South of the 1960s and 1970s, then, clearly transcended partisan boundaries and proved useful to Americans of all political persuasions.

There was of course a great irony in Americans looking to the South, especially the white South, during this period. This was, of course, during the civil rights era, a public relations disaster for white southerners. But even in this moment, when white southerners were routinely lambasted—often rightly—as pariahs, southernness was a highly malleable concept suitable for addressing a host of cultural and political needs. In part, these imaginings in the 1960s and 1970s were distinguished from earlier constructions of the South because they happened in the midst of a revolutionary racial transformation in the region. Notably, at this controversial time, the South could still function in myriad ways: as a bigoted wasteland, as a region on the mend and learning to repair its racial schism, and finally, maybe even as a racially reformed locale, a model for others to emulate. In this final vision, observers deemed the South capable of teaching the rest of the country a thing or two about the United States’s failures to secure true equality for all of its citizens. This state of affairs was unprecedented, as it gave Americans license to think about the white South as both a malevolent and a redemptive force, with its racial meaning enjoying a similar flexibility.

At the same time, such imaginings, which regularly portrayed white southerners in anachronistic terms as wise, familial-oriented rustics, occurred as the South continued its dizzying movement toward political and economic integration with the nation at large. In the 1960s and 1970s, it was still commonplace for cultural and political figures to cast white southernness in largely—and appealingly—rural terms, from Linda Ronstadt smiling amusedly while lounging in a pig pen—a barefoot hippie chick down on the farm—on the cover of her 1970 album Silk Purse, to presidential hopeful Jimmy Carter, in his 1975 book Why Not the Best?, comparing his Depression-era boyhood in the Georgia countryside to the “farm life of fully 2,000 years ago.” Out-of-time fantasies of the South were out of step with much of the actual lived experience of white southerners in the sixties and seventies, but that was beside the point. They were nevertheless powerful symbols of traditionalism and stability at a time when so many Americans felt that their country had lost its way politically, socially, and spiritually.

This imagined South, then, operated in the realm of myth. The purpose—and power—of myths, the French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss explained, is contained in their ability to seemingly address and perhaps symbolically resolve problems that in reality have no solution. This is precisely why an outmoded white South appealed widely to a variety of Americans during and immediately after the civil rights era. With racial and cultural hierarchies in flux, it should come as no surprise that a region known for its traditionalism (and less charitably, its backwardness) should see its stature as a national myth worthy of emulation grow. Apparent paradoxes did not necessarily matter. In the 1970s, for example, one could dig the interracial sounds—and lineup—of the southern rockers in the Allman Brothers Band while also singing along to Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama,” a song that the Florida band repeatedly played against the backdrop of an enormous Confederate flag. These groups, to some extent, depicted very different versions of white southernness. Still, they were united in their endorsement of white southern masculine rebellion as an antidote to what contemporary reactionary forces bemoaned as the “feminization” of US society.

While receiving ample psychological succor from the imagined South in the 1960s and 1970s, Americans’ reliance on its myth was ultimately problematic. On balance, even in its most positive forms, like the character of Andy Griffith’s folksy southern sheriff on his hugely successful TV show (1960-1968), fantasies about white southerners too often presented them—dubiously—as the keepers of lost values rather than as real, three-dimensional people. Such condescension remains with us today, in both negative and positive commentaries on white southernness. In the minds of some pundits and politicians, white southerners are an essential part of the “real America,” antithetical to the purported inauthenticity and permissive liberalism of blue state America.

On the other hand, they are easily disregarded as “dumb southerners,” whose homeland always marks them as an easy joke when needed. No matter the circumstances, imagining the South remains an ultimately selfish endeavor. It requires a person to reinforce and exploit stereotypes about the region in a questionable effort to assuage their personal apprehensions about the state of America. For someone so notoriously thin-skinned and concerned about others’ opinions of him, it is far from shocking that Donald Trump would spout hoary clichés about white southerners to alleviate his deep-seated insecurities while, at other times, broadly praising that group. Americans—the president included—cannot help but love and hate the South at the same time; it is one of their favorite, most essential, pastimes.