History Doyen: David Brion Davis

What They're Famous For

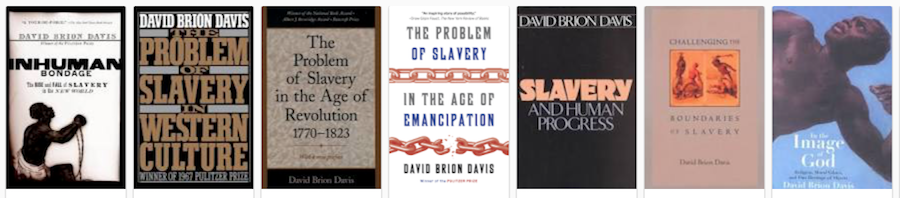

David Brion Davis is the Sterling Professor of History Emeritus at Yale university and taught there from 1970 to 2001. He is currently Director Emeritus of Yale's Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition, which he founded in 1998 and directed until 2004. Davis received his PhD from Harvard University in 1956. His books include Homicide in American Fiction (1957); The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture (1966); The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution (1975); Slavery and Human Progress (1984); Revolutions: American Equality and Foreign Liberations (1990); In the Image of God: Religion, Moral Values, and Our Heritage of Slavery (2001), and Challenging the Boundaries of Slavery (2003).

Davis's latest book InHuman Bondage: Slavery in the New World was just released in April. He is currently returning to complete a major work he has been doing for many years, a two-volume The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Emancipation. Earlier volumes in this series The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture won a Pulitzer Prize, and The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution won National Book Award for History and Biography, the AHA's Albert Beveridge Award, and the Bancroft Prize.

Professor Davis has received numerous awards during his distinguished career. Most recently, in 2004 he was awarded by the Society of American Historians the Bruce Catton Prize for Lifetime Achievement. Also in 2004 he was awarded the New England History Teachers' Association's Kidger Award in recognition for his nine years of summer seminars for teachers on the origins and nature of New World slavery.

Davis is considered the most pre-eminent historian of slavery as Ira Berlin claimed "No scholar has played a larger role in expanding contemporary understanding of how slavery shaped the history of the United States, the Americas and the world than David Brion Davis." Davis has stated in a an interview the greater purpose in his study of the slavery; "I hope that my writings on slavery and abolitionism will continue to help people--especially non-academics--understand the roots and foundations of the great racial dilemma that America and other countries still face."

Personal Anecdote

I would like to say a few words in opposition to the view, expressed nowadays by far too many educators, that history is a boring and antiquarian diversion, that we should "let bygones be bygones," "free" ourselves from a dismal and oppressive past, and concentrate on a fresh and better future. I have long and fervently believed that a consciousness of history is one of the key factors that distinguishes us from all other animals -- I mean the ability to transcend an illusory sense of NOW, of an eternal present, and to strive for an understanding of the forces and events that made us what we are. Such an understanding is the prerequisite, I believe, for all human freedom. Obviously history can be used in ideological ways to justify the worst forms of aggression and oppression. But that fact underscores the supreme importance of freeing ourselves from such distortions and searching, as far as possible, for a true and balanced picture of the past. I hope I can illustrate this point by briefly describing the personal path I took in becoming a historian of slavery and antislavery.

Because my parents were journalists for a time and then became productive writers of excellent fiction and non-fiction, despite their lack of a college education, I spent many hours of my childhood traveling from coast to coast in the back seats of cars made in the 1930s, mostly Plymouths with a sleek Mayflower on the front of the hood. This meant that I experienced considerable diversity with respect to teachers and fellow students as I literally attended ten different schools from kindergarten to the twelfth grade, schools in such places as Denver, Beverly Hills, Manhattan, Carmel, California, and Hamburg, New York. In fact, I attended five high schools in the four years from the ninth to the twelfth grade. And whatever achievements I've had in the subsequent 61 years are in large part dependent on my luck in having truly extraordinary teachers in the third, fifth, and sixth grades (in three different schools in three different states), in addition to an inspired teacher of general science in the eighth and ninth grades, and a phenomenal teacher of English literature and writing in my senior year of high school.

When I graduated from high school in early June 1945, there were no thoughts about college or a future career. I was immediately drafted and plunged into combat training as an infantryman for the planned invasion of Japan in the fall. The appalling casualty figures from the ongoing battle for Okinawa, coupled with our officers' accounts of their own combat experiences, gave a sobering perspective to our accuracy at the firing range and to our desired skill in throwing hand grenades, shooting flame throwers, and attacking mock Japanese villages defended by booby traps and dummy Japanese snipers hidden in the trees. But then as a direct result of the Hirosh'ima and Nagasaki bombings, I found myself on a troopship headed for a fascinating and highly influential year in what had very recently been Nazi Germany. Thanks to some high-school German, I soon became a member of the American Security Police, arresting black marketers, escaped SS officers, and on one occasion, a Polish soldier who had raped and given gonorrhea to a six-year-old German girl (who, in a painful interview, gave me the information I needed).

Clearly I was untrained and was far too immature for such awesome responsibilities. But living in the shadow of the Holocaust and amid the rubble and ruins of the world's greatest war did have a maturing effect and prompted serious thought on what to do with my life.

In a long letter to my parents and 85 year-old grandmother, written on February 17, 1946, I described the appalling racism that many white American soldiers displayed when they encountered black soldiers in the segregated army, and then turned to some thoughts about college in the years ahead. Though expressing my desire to take courses in English, history, French, anthropology, and astronomy, I finally emphasized that "I quite definitely want to go into this physics business as well as the necessary accompanying mathematics. I think I could get quite interested in physics" [which I had taken in high school; and upon first hearing the news of Hirosh'ima, I thought of the drastic implications of e=mc square].

But by October 9th, 1946 I had completely changed my mind. I will quote the new thoughts, clearly influenced by nearly a year's exposure to the war's devastation, in some detail: "I've been thinking over the idea of majoring in history, continuing into post-graduate research, and finally teaching, in college, of course, and have come to some conclusions which may not be original, but are new as far as I'm concerned. It strikes me that history, and proper methods of teaching it, are even more important at present than endocrinology and nuclear fission. I believe that the problems that surround us today are not to be blamed on individuals or even groups of individuals, but on the human race as a whole, its collective lack of perspective and knowledge of itself. That is where history comes in."

Actually, at age 19 I knew very little about history and had not been blessed with especially good history teachers in high school. But I went on: "There has been a lot of hokum concerning psychoanalysis, but I think the basic principle of probing into the past, especially the hidden and subconscious past, for truths which govern and influence present actions, is fairly sound. Teaching history, I think, should be a similar process. An unearthing of truths long buried beneath superficial facts and propaganda; a presentation of perspective and an overall, comprehensive view of what people did and thought and why they did it. When we think back into our childhood, it doesn't do much good to merely hit the high spots and remember what we want to remember --- to know why we act the way we do, we have to remember everything. In the same way it doesn't help much to teach history as a series of wars and dates and figures, the good always fighting the bad, the bad usually losing. Modern history especially, should be shown from every angle. The entire atmosphere and color should be shown, as well as how public opinion stood, and what influenced it."

"Perhaps such teaching could make us understand ourselves. It would show the present conflicts to be as silly as they are. And above all, it would make people stop and think before blindly following some bigoted group to make the world safe for Aryans or democrats or Mississippians. During the 1930s there were many advances in the methods of teaching history. The effect cannot be overemphasized. After talking with many GIs of the 18-19 year old age group, I'm convinced that the recent course in modern European history did more good than any other single high school subject. And that is just a beginning."

"There are many other angles, of course, but I am pretty well sold on the history idea at present. It is certainly not a subject, as some think, which is dead and useless. You know the line, 'why should I be interested in history? That's all past. We should concern ourselves with the present and future --- cars, vacuum cleaners, steel mills, helicopters, atom bombs, juke boxes, movies --- and on into [Aldous] Huxley's [Brave New] world of soma, baby hatcheries, feelies (instead of movies).'"

"It is extremely difficult to tell whether an interest like this is temporary or permanent. It does fit into my other plans very nicely. After I once get into school and out of this vacuum, I'll be able to narrow my sights and bring things into focus. At least I've got something to talk about."

As it happened, my road to becoming a historian was not quite as direct as this letter of 1946 might suggest. At Dartmouth I majored in philosophy, in part because the History Department was then so weak. But I focused on the history of philosophy and the history of evolving conceptions of human nature. And beginning in 1953, I did end up teaching American history for 47 years: a year at Dartmouth, 14 years at Cornell, and 32 years at Yale (2 years of which were actually at Oxford and the French Ecole des Hautes Etudes, in Paris).

Quotes By David Brion Davis

From David Brion Davis in "The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture"

Many historians have exaggerated the antithesis between slavery and Christian doctrine. The contradiction, as we have tried to show, lay more within the idea of slavery itself. Christianity provided one way of responding to this contradiction, and contained both rationalizations for slavery and ideals that were potentially abolitionist. The significant point, however, is that attitudes were interwoven with central religious concepts. This amalgam, which had developed through antiquity, was foreshadowed in Judaism and Greek philosophy.

In one sense slavery was seen as a punishment resulting from sin or from a natural defect of the soul that precluded virtuous conduct. The slave was a Canaanite, a man devoid of Logos, or sinner who scorned the truth. Stoics and Christians endeavored to distinguish the true from apparent slave, but physical bondage always suffered from the guilt of association.

In a second sense slavery was seen as a model of dependence and self-surrender. For Plato, Aristotke, and Augustine this meant that it was a necessary part of a world that required moral order and discipline; it was the base on which rested an intricate and hierarchial pattern of authority. Yet Jews called themselves the slaves of Yahweh, Christians called themselves the slaves of Christ. No other word so well expressed an ultimate in willing devotion and self-sacrifice.

In a third sense slavery stood as the starting point for a divine quest. It was from slavery that hebrews were delivered and from which they aquired their unique mission. It was slavery to desire and social convention that Cynics and Stoics sought to overcome by self-discipline and indifference to the world. And it was from slavery to the corrupted flesh of Adam that Christ redeemed mankind.

For some two thousand years men thought of sin as a kind of slavery. One day they would come to think of slavery as sin.

From David Brion Davis writing in the "The Importance of History"

I'm passionately committed to the cause that distinguishes us from all other animals -- the ability to transcend an illusory sense of NOW, of an eternal present, and to strive for an understanding of the forces and events that made us what we are. Such an understanding is the prerequisite, I believe, for all human freedom. In one of my works on slavery I refer to "a profound transformation in moral perception" that led in the eighteenth century to a growing recognition of "the full horror of a social evil to which mankind had been blind for centuries." Unfortunately, many American historians are only now beginning to grasp the true centrality of that social evil -- racial slavery --- throughout the decades and even centuries that first shaped our government and what America would become.

From David Brion Davis discussing his new book "Inhuman Bondage" in a recent speaking engagement.

Inhuman Bondage is designed to illuminate our understanding of American slavery and antislavery by placing this subject within the much larger contexts of the Atlantic Slave System and the rise and fall of slavery in the New World. It is not a comprehensive or encyclopedic survey of slavery in every New World colony, but rather an exploration of America's greatest historical problem and contradiction, which deeply involved such disparate places as Britain, Spain, Haiti, and ancient Rome.

The book begins with the dramatic Amistad story in 1839-1841, which highlights the multinational character of the Atlantic Slave System, from Sierra Leone to Cuba and Connecticut, as well as the involvement of the American judiciary, the presidency (and a former president), the media, and both black and white abolitionists. I then move on to the ancient foundations of modern slavery in the Bible, ancient Babylonia, and ancient Greece and Rome, before turning to the long and complex origins and development of anti-black racism, extending from medieval Arab states to the early Iberian obsession with purity of blood and the racist theorizing of such major figures of the European Enlightenment as Voltaire, Hume, and Kant. Chapter Four, on "How Africans Became Intrinsic to New World history," rejects various economic deterministic theories and emphasizes the contingent ways in which greed and a desire for profit became fused with issues of religion and ethnic identity. It is in this chapter that I describe the trading for slaves along the African coast and include vivid descriptions of the atrocious overpacking and dehydration on slave ships crossing the Atlantic. Above all, I emphasize that racial slavery became an intrinsic and indispensable part of New World settlement --- that our free and democratic society was made possible by the massive exploitation of slave labor.

I then move on to the nature and character of slavery in Portuguese Brazil, the British Caribbean, and colonial North America. I have no time here to summarize the many topics and arguments, but will simply say that the remaining chapters deal with the problem of slavery in the American Revolution, and in the French and Haitian Revolutions, before I give a detailed examination of slavery in the nineteenth-century South. Before turning to chapters on American and British abolitionism, I compare American slave resistance and conspiracies with three massive slave revolts in the British Caribbean. Though Chapter Fourteen focuses on the politics of slavery in the United States, it also considers British-American relations and the impact of Britain's emancipation of 800,000 slaves, in 1834, on Southern fears and suspicions of the North. Chapter Fifteen attempts to put the American Civil War and slave emancipation within an international context. In the Epilogue I consider the influence of the American Civil War on the slave emancipations in Cuba and Brazil.

The crucial and final point I want to make is that a frank and honest effort to face up to the darkest side of our past, to understand the ways in which social evils evolve, should in no way lead to cynicism and despair, or to a repudiation of our heritage. The development of maturity means a capacity to deal with truth. And the more we recognize the limitations and failings of human beings, the more remarkable and even encouraging history can be.

Acceptance of the institution of slavery, of trying to reduce humans to something approaching beasts of burden, can be found not only in the Bible but in the earliest recorded documents in the Mesopotamian Near East. Slavery was accepted for millennia, virtually without question, in almost every region of the globe. And even in the nineteenth century there was nothing inevitable or even probable about the emancipation of black slaves throughout the Western Hemisphere. This point is underscored by the appalling use of coerced labor even in the twentieth century, especially in various forms of gulags or concentration camps, the outcome of which I saw as a young American soldier. Above all, I conclude, we should consider the meaning, in the early twenty-first century, of the historically unique antislavery movements which succeeded in overthrowing, within the space of a century, systems of inhuman bondage that extended throughout the Hemisphere -- systems that were still highly profitable as well as productive.

About Davis Brion Davis

● A magnificent work done in the finest traditon of historical scholarship." -- C. Vann Woodward, Yale University reviewing "The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture"

● "A magnificent history of ideas....It will remain a magnificent contribution to intellectual and social history....Will be studied for decades to come." -- Eugene D. Genovese, Journal of Southern History reviewing "The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture"

● "A large, immemsely learned, readable, exciting, disturbing...volume, one of the most important to have been published on the subject of slavery in modern times. -- M.I. Finley, The New York Review of Books reviewing "The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture"

● "In...The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture, David Brion Davis displayed his mastery not only of a vast source of material, but also of the highly complex, frequently contradictory factors that influenced opinion on slavery. He has now followed this up with a study of equal quality....No one has written a book about the abolition of slavery that carries the conviction of Professor Davis's book. And this rich and powerful book will, I am sure, stand the test of time--scholarly, brilliant in analysid. beautifully written." -- J. H. Plumb, The New York Times Book Review reviewing "The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution"

● "The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution by David Brion Davis is a work of majestic scale, written with great skill. It explores the growing consciousness, during a half century of revultionary change, of the oldest and most extreme form of human exploitation. Concentrating on the Anglo-American experience, the historian also pursues his theme wherever it leads in western culture. His book is a distinguished example of historical scholarship and art." -- From the National Book Award citation for "The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution"

● "A tour de force.... Could not be more welcome.... Davis follows the large story of slavery into all corners of the Atlantic world, demonstrating that hardly anyone or anything was untouched by it. He is particularly interested in the way ideas shaped slavery's development. But 'Inhuman Bondage' is not a history without people. Princes, merchants and reformers of all sorts play their role, though Davis gives pride of place to the men and women who suffered bondage. Drawing on some of the best recent studies, he not only adjudicates between the arguments, but also provides dozens of new insights, large and small, into events as familiar as the revolt on Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) and the American Civil War.... An invaluable guide to explaining what has made slavery's consequences so much a part of contemporary American culture and politics." -- Ira Berlin, The New York Times Book Review reviewing "Inhuman Bondage"

● "Davis masterfully navigates the long history of slavery from ancient times to its abolition in the 19th century.... Succeeds heroically in wrestling a vast amount of material from diverse cultures. The result is a sinewy book that combines erudition and everyday detail into a gripping, often surprising, narrative." -- Fergus M. Bordewich, Wall Street Journal reviewing "Inhuman Bondage"

● "David Brion Davis has been the preeminent historian of ideas about slavery in the Western world since the early modern period.... Davis, a leading practitioner of intellectual and cultural history, has now gone far beyond the history of ideas and attempted to study New World slavery in all its ramifications, social, economic, and political, as well as intellectual and cultural.... He convincingly demonstrates that slavery was central to the history of the New World." -- George M. Fredrickson, The New York Review of Books reviewing "Inhuman Bondage"

● "David Brion Davis, our greatest historian of slavery and abolition, weaves together here one of the central stories of modern world history--and does so with a power, authority, and grace that is his alone." -- Edward L. Ayers reviewing "Inhuman Bondage"

● "Ranging from ancient Babylonia to the modern Western Hemisphere, David Brion Davis offers a concise history of slavery and its abolition that once again reminds us why he is the foremost scholar of international slavery. There is no more up-to-date account of this pivotal aspect of the world's history." -- Eric Foner reviewing "Inhuman Bondage"

● "In this gracefully fashioned masterpiece, David Brion Davis draws on a lifetime of scrupulous scholarship in order to trace the sources and highlight the distinctiveness of America's central paradox by situating it in both its New World and Western contexts. His powerful narrative is enhanced and deepened by persuasively rendered details. For students of slavery, and of American history more generally, it is simply indispensable. With all the makings of a classic, Inhuman Bondage is the glorious culmination of the definitive series of studies on slavery by one of America's greatest living historians." -- Orlando Patterson reviewing "Inhuman Bondage"

● "Inhuman Bondage is a magisterial achievement, a model of comparative and interdisciplinary scholarship, and the best study we have of American slavery within the broader context of the New World. It is also a powerful and moving story, told by one of America's greatest historians." -- John Stauffer reviewing "Inhuman Bondage"

● "This brilliant and gripping history of slavery in the New World summarizes and integrates the scholarship of the past half-century. It sparkles with insights that only an innovator of David Brion Davis's caliber could command." -- Robert William Fogel reviewing "Inhuman Bondage"

Teaching Positions:

Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, instructor in history and Ford Fund for the Advancement of Education intern, 1953-54;

Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, assistant professor, 1955-58, associate professor, 1958-63, Ernest I. White Professor of History, 1963-69; Yale University, New Haven, CT, professor of history, 1969-72, Farnham Professor of History, 1972-78, Sterling Professor of History, 1978--, currently emeritus, director of Gilder Lehrman Center for the study of slavery, resistance, and abolition.

Fulbright lecturer in India, 1967, and at universities in Guyana and the West Indies, 1974. Lecturer at colleges and universities in the United States, Europe, and the Middle East, 1969--.

Area of Research:

Slavery in the Western World and America, Antebellum America, Intellectual history

Education:

Dartmouth College, A.B. (summa cum laude), 1950;

Harvard University, A.M., 1953, Ph.D., 1956;

Oxford University, M.A., 1969;

Yale University, M.A., 1970.

Major Publications:

- Homicide in American Fiction, 1798-1860: A Study in Social Values, (Cornell University Press, 1957).

- The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture, (Cornell University Press, 1967).

- Was Thomas Jefferson an Authentic Enemy of Slavery?, (Clarendon Press, 1970).

- The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, 1770-1823, (Cornell University Press, 1975, reprinted, Oxford University Press, 1999).

- (With others) The Great Republic: A History of the American People, (Little, Brown, 1977, revised edition, 1985).

- pamphlet The Emancipation Moment, 1984.

- Slavery and Human Progress, (Oxford University Press, 1984).

- Slavery in the Colonial Chesapeake (pamphlet), (Colonial Williamsburg, 1986).

- From Homicide to Slavery: Studies in American Culture, (Oxford University Press, 1986).

- Revolutions: Reflections on American Equality and Foreign Liberations, (Harvard University Press, 1990).

- (Coauthor) The Antislavery Debate: Capitalism and Abolitionism As a Problem in Historical Interpretation, edited by Thomas Bender, (University of California Press, 1992).

- In the Image of God: Religion, Moral Values, and Our Heritage of Slavery, (Yale University Press, 2001).

- Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World, (Oxford university Press, 2006).

- Challenging the Boundaries of Slavery, (Harvard University Press, 2003).

Editor, Contributor, Joint Author:

- Antebellum Reform, (Harper, 1967).

- The Slave Power Conspiracy and the Paranoid Style, (Louisiana State University Press, 1969).

- (Editor) The Fear of Conspiracy: Images of Un-American Subversion from the Revolution to the Present, (Cornell University Press, 1971).

- Antebellum American Culture: An Interpretive Anthology, (Heath, 1979, reprinted, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997).

- (With Steven Mintz) The Boisterous Sea of Liberty: A Documentary History of America from Discovery through the Civil War,(Oxford University Press, 1998).

Contributor to books, including: The Stature of Theodore Dreiser, edited by Alfred Kazin and Charles Shapiro, (Indiana University Press, 1955); Twelve Original Essays on Great American Novels, edited by Shapiro, (Wayne State University Press, 1958); Perspectives and Irony in American Slavery, edited by Harry Owens, (University of Mississippi Press, 1976); Slavery and Freedom in the Age of the American Revolution, edited by Ira Berlin and Ronald Hoffman, (University of Virginia Press, 1983); and British Capitalism and Caribbean Slavery, edited by Barbara Solow and Stanley L. Engerman, (Cambridge University Press, 1987).

Awards:

Pulitzer Prize, 1967, for The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture.

National Book Award for history, and Bancroft Prize, both 1976, both for The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, 1770-1823.

2004 Bruce Catton Prize of the Society of American Historians for lifetime achievement;

2004 Kidger Award from the New England History Teachers Association given to honor his devotion to teaching;

Corresponding fellow, British Academy, 1992; Litt.D. from Columbia University, 1999;

Presidential Medal for Outstanding Leadership and Achievement, Dartmouth College, 1991;

Corresponding fellow, Massachusetts Historical Society, 1989;

L.H.D., University of New Haven, 1986;

Fulbright traveling fellow, 1980-81;

National Endowment for the Humanities, research grants, 1979-80 and 1980-81, and fellowship for independent study and research, 1983-84;

Litt.D., Dartmouth College, 1977;

Henry E. Huntington Library fellow, 1976;

Albert J. Beveridge Award, American Historical Association, 1975;

Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences fellow, 1972-73;

National Mass Media Award, National Conference of Christians and Jews, 1967;

Anisfield-Wolf Award, 1967;

Guggenheim fellow, 1958-59.

Additional Info:

Davis served as President of the Organization of American Historians for the 1988-1989 term.

Commissioner, Orange, CT, Public Library Commission, 1974-75;

Associate director, National Humanities Institute, Yale University, 1975.

Contributor to professional journals and other periodicals, including New York Times Book Review, Times Literary Supplement, New York Review of Books, Washington Post Book World, New Republic, and Yale Review.

Military service: U.S. Army, 1945-46.