What I’m Reading: An Interview With Historian of Mexico Pablo Piccato

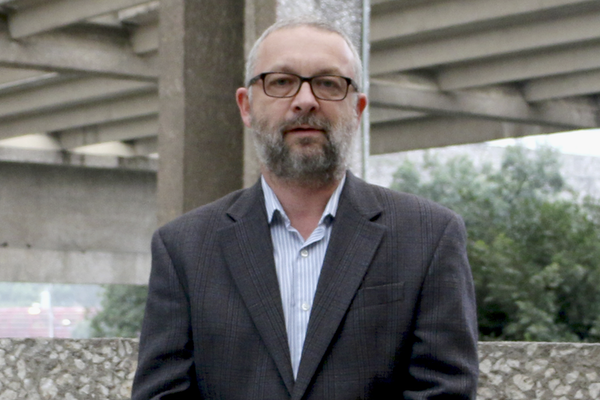

Pablo Piccato got his B.A. in History at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, in 1989, and his Ph.D. from the University of Texas at Austin in 1997. He is professor at the Department of History, Columbia University where he teaches on Latin America, Mexico and the history of crime. His research focuses on modern Mexico, particularly on crime, politics, and culture. He has taught as visiting faculty in universities in Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Italy and France, and has been director of Columbia’s Institute of Latin American Studies. His books include Congreso y Revolución, 1991; City of Suspects: Crime in Mexico City, 1900-1931 (2001), The Tyranny of Opinion: Honor in the Construction of the Mexican Public Sphere (2010), and most recently A History of Infamy: Crime, Truth, and Justice in Mexico (2017), which won the María Elena Martínez Prize for the best book in Mexican History from the Conference on Latin American History.

What books are you reading now?

Reading fiction is a basic necessity for me, even when I am in the middle of research or teaching seasons. Right now I am readingThe Star Diaries by Stanislaw Lem, in the Spanish version. Science fiction creates worlds that are possible. They can be removed in time and space but they have a connection with our present. In a way, all science fiction is about colonialism. Lem is a great critic of science and politics: he plays with the encyclopedic knowledge of those possible worlds, and makes fun of our ridiculous anthropocentrism. His scientists of the future try to intervene in history to bring the world closer to their idea of perfection, but fail miserably because of bureaucratic intrigues. I’m also going slowly through Robert A. Caro’s second volume of Lyndon B. Johnson’s biography, Means of Ascent. I admire Caro’s narrative drive, but also his lack of concern about how long it will take to get to fully understand his subject.

What is your favorite history book?

I have to think about several books that were important for me at different times: at the beginning of college, Charles Gibson’s The Aztecs under Spanish Rule, showed me the power of old and neglected sources to reveal a social structure that survived conquest. I read it in Spanish translation, in a battered copy at my university’s library, and it made me want to become a historian of Mexico in the sixteenth century. Just before graduate school, William B. Taylor, Drinking, Homicide and Rebellion in Colonial Mexican Villages showed me the value of judicial sources and the way in which transgression could be woven into the fabric of an apparently stable system of domination. When I was in Austin I discovered the richness of modern urban spaces and sociabilities through Judith Walkowitz, City of Dreadful Delight, and Margareth Rago, Os prazeres da noite: two wonderful books about transgression and desire set in urban spaces where women challenged the privileges of male gaze.

Why did you choose history as your career?

I’m not sure. I was finishing high school and I had to decide what career to follow at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. I guess I applied to History instead of Philosophy because I felt I had to understand the reasons why I was there: my father had to leave Argentina because of the political repression of the mid-seventies and we all moved to Mexico. Both countries still represent the questions of history for me, one in short and recent episodes of crises, and the other as long-term processes of stability and transformation. In those years, Argentina went through a process of internal political fragmentation that lead to a bloody military dictatorship. I discovered that Mexico had a rich pre-Hispanic and colonial history, a massive social revolution, and a regime that still welcomed exiles. Studying history may have been my way of honoring that complex combination in space and time that was Mexico City in 1982. I’m pretty sure I did not go into English Literature because I was afraid of spoiling the pleasure of reading fiction.

What qualities do you need to be a historian?

You have to be able to tell a story, but you also have to explain the past. Both require to be attentive to the present. The reasons why people approach history are always changing, so the historian has to have one foot firmly planted on her circumstances, and to read other historians with that in mind. But she also has to be willing to go into the archive or the library or the interview and let the sources take her into unexpected places. You have to be meticulous in preparation but also be ready for surprises, and keep a good database with your notes because you never know how are you going to use the source you read today. Without a particular combination of this sense of wonder with a maniacal concern about detail, one cannot go very far as a historian. And you also need patience: to spend many hours reading sources that do not seem to be productive, to wait until your files are delivered by the archivist, to look for a book that seems to have disappeared from libraries.

Who was your favorite history teacher?

Again: different people come to mind at different times. A teacher of Mexican history in middle school whose name I’ve forgotten was the first to show me that the past can be explained with clarity, and told me to visit the National Library, at the time still in an old church building in downtown Mexico City. Arturo Sotomayor, in high school, spoke with passion about modern Mexican history, in a way that gave it a relevance I did not imagine until then, and that I am still trying to fully apprehend. In college, Eduardo Blanquel taught me how to read and discuss primary sources, and I’ve been following his model and trying to do the same in my classes ever since. My doctoral adviser in Austin, Jonathan C. Brown, showed me how to think and then write clearly while I was immersed in a project that could have easily gone out of control. He is my model of a graduate mentor because he knows when to be critical and when to let you be.

What is your most memorable or rewarding teaching experience?

After a particularly difficult class trying to understand Descartes’s Discourse on the Method, in my Contemporary Civilization section at Columbia. We were tired and not sure where the discussion was going. A student smiled and laughed, I laughed, and the entire group started laughing out loud, so much so I had to end the class right there. I guess we all agreed that we would never finish dissecting the book into its smaller parts, but also that the enterprise was foolish anyway. The lesson, I guess, is that you have to stop reading at one point, and move on.

What are your hopes for history as a discipline?

That historians claim a stronger voice in the public sphere to talk about the present under the light of the past. This does not mean we have to become antiquarians who claim there is nothing new under the sun, or determinists that try to establish the laws of evolution. We can help shaping historical discussions that will make sense of the present with a proper historical perspective. We can compare places and times, and remind the public that their horizon should not be an op-ed about the last five years, or a rigid school narrative about the last two hundred years. Today that operation is more important than ever: we need to understand the history of fascism and racism if we are going to appreciate both the radical threat and the unavoidable roots of Trump’s government. Yet nothing of this will be possible if we stop training historians who can do serious and deep research, organize large amounts of data, write coherently and have a lasting impact as teachers and mentors.

Do you own any rare history or collectible books? Do you collect artifacts related to history?

Not really, unless you count a small collection of 1940s Mexican comic books about Chucho Cárdenas, the reporter-detective. I enjoy looking at old objects in museums and libraries. They help me imagine how they were used, circulated, touched and valued in times past. Yet I had never had the impulse to own them. They should be in a public place where others can come close to them and imagine those uses for themselves.

What have you found most rewarding and most frustrating about your career?

The most rewarding aspect has been my work with students and colleagues. It is tempting to think about the work of the historian as solitary and individualistic, as if we were authors inspired by rare epiphanies that only occur after long years of painful research. The reality is that our conversations in seminars, workshops, conferences, the cafés close to archives and libraries, and at the occasional bar, play a decisive role to understand the possible contribution of our work. Often when I write I imagine the text as a conversation with other historians who can criticize my arguments, be skeptical about my sources, but also, eventually appreciate what I am trying to say. Co-writing has always been a good experience for me and sometimes I wonder why we historians are so reluctant to write in teams compared to other scholars. Another reward of the job is to come across readers who understand, sometimes more cogently than myself, what my books and articles do.

I guess all institutions can be frustrating, even as they make possible the material conditions and the collaborations that are essential for our work. I have experienced the combination of mismanagement and petty authoritarianism of large institutions since college, but I have also seen the advantage of being patient and trying to change them from the inside. I guess I’ve been fortunate to have the option. But I am aware that biases permeate academic life, even if we refuse to recognize them. I am still learning how seemingly small interactions can have large consequences for people’s careers. Along with a wonderful group of colleagues from different disciplines at Columbia I participated last year in the production of a report on harassment and discrimination in the social sciences (https://www.fas.columbia.edu/home/diversity-arts-and-sciences/ppc-equity-reports). The experience helped me understand moments in my own career that I had tried to forget, perhaps because they undermined my confidence as a young scholar. It also helped me appreciate how effective serious research and collective work can be when we try to confront the problems derived from bias and inequality in academic life. The committee work that I have to do, as all of my colleagues, reminds me that institutions are not brands or buildings but people who come together with a purpose.

How has the study of history changed in the course of your career?

The fundamental change in recent decades has been a new ability of the discipline to synthesize methodologies and approaches that twenty years ago seemed to be isolated from each other. During graduate school, in the nineties, I saw the tension between cultural history and other subfields that defined themselves as “harder” in terms of their use of evidence and interpretive models. It was as if two fundamentally opposed paradigms of historical work were on a collision course. But if you look at the best programs in my field today, in Mexico and the United States, you can see that they have avoided the temptations of specialization and have encouraged historians to cross disciplinary divides, training students in a generous way. So, instead of a field divided between “postmodernists” and “positivists”, as many predicted twenty years ago, we have an explosion of work that engages social, cultural, economic, political, intellectual, environmental, migration and legal history, to name a few. We still have some colleagues who concern themselves with patrolling the boundaries of their area of expertise, but they do not have the influence they think they have.

What is your favorite history-related saying? Have you come up with your own?

I love “May you live in interesting times”: it might sound as an ironic curse but now I hear it as a blessing of sorts. We all live in interesting times, whether we like it or not.

What are you doing next?

I am starting a project on poetry and politics in nineteenth-century Mexico. I am still far from producing anything of value but I am enjoying the process of learning how to read poetry. Mexico and other Latin American countries had a rich literary life in the nineteenth century. Some authors have survived, particularly from the second half of the century, like Sarmiento, Martí or Machado de Assis, but I think few historians appreciate yet the creativity and intensity of that world of fiction and poetry, a world that was shared by many people, across classes, in oral and written form. It was a realm of cultural production where Latin American authors and readers could be as productive and free from the legacies of colonialism as they wished to. Poetry in particular was a central medium for political speech during the era that we can roughly classify as romantic.

I started this project with some trepidation, because I knew I would enjoy the research. I now understand Terry Eagleton when he writes that “Literary critics live in a permanent state of dread--a fear that one day some minor clerk, in a government office, idly turning over a document, will stumble upon the embarrassing truth that we are actually paid for reading poems and novels.” I already had a sense of dread when I was reading crime fiction for my previous book but I managed to overcome it when I confirmed that narrative was a privileged source to understand social ideas about crime and justice. Poetry is similarly promising if we read it as a medium that expands the communicative possibilities of words and images.