Teacher Pay, Presidential Politics, and New York’s Modest Proposal of 1818

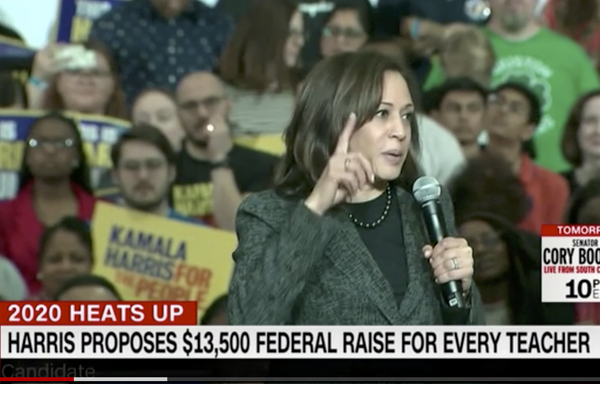

With her recent pledge to raise teacher salaries, Senator Kamala Harris has guaranteed the issue will be a key part of the 2020 Democratic Party primary debates. Since the slew of teacher strikes began last year, the question of teacher pay has shoved its way to the front in American politics. We shouldn’t be surprised; teacher pay has always been one of the thorniest issues in public-school administration. The first generation of amateur administrators considered one solution that will seem shocking only to those who do not understand the desperate politics of school budgets.

The fact that teacher pay is a difficult issue should not come as any surprise. Public schools, after all, generate no profit and teacher salaries make up the biggest portion of budgets. Even a small decrease—or a reduced increase—in teacher pay can create a lot of wiggle room in a struggling school-district budget. It is always a temptation for administrators in straitened circumstances to dream of cutting salaries.

The most experienced and cynical teachers, then, won’t be surprised to hear of one plan from the earliest days of public education in the United States. Two centuries ago, well-heeled philanthropists of the New York Free School Society (FSS) operated two schools for the city’s least affluent children.

Money was always tight. As the trustees noted in 1820, the FSS cobbled together funds from “the donations and Legacies of charitable Individuals, the bounty of the Corporation [i.e. city government] and the munificence of the Legislature.” Their funding was never guaranteed and it was never enough; the organization lurched from one financial crisis to the next.

The dilettantish leaders had not expected this. They thought that a new plan of organizing their teachers would prevent such financial shortfalls. According to this plan, called “monitorial” or “Lancasterian” education, charismatic English school-founder Joseph Lancaster promised that thousands of children from low-income families could learn to read and write without expensive teacher salaries. One teacher would supervise “monitors,” student helpers who would do all the hard work of teaching.

Experienced school leaders might have seen the problem coming, but New York’s administrators had more enthusiasm than experience. They were surprised to find that their monitors did not want to work for nothing. When the monitors were asked to do so, many of them simply left to open entrepreneurial schools of their own or to take jobs in other fields. The ones who stayed demanded salaries like the other teachers.

The FSS leaders were in a bind. Their budget was based on the free labor of monitors. They could not afford to pay more teacher salaries. In 1818, they wondered if they might import a traditional English solution. In October, 1818, the FSS board of trustees considered a plan to turn their young teachers—the monitors—into formal apprentices. The financial benefits would be enormous.

According to the long tradition of apprenticeship, young people bound by indentures could be forced to work without salary until they turned twenty-one. In exchange for learning the art and mysteries of the trade of teaching, these young apprentices would be legally bound to serve the FSS for free until they aged out.

The trustees created a model indenture form, one that would bind teachers until they turned twenty-one,

during all which time the said apprentice shall faithfully serve said [Free School] Society, obey their lawful commands and the lawful commands of such teacher and teachers and their agent or agents . . . for that purpose.

Beyond saving money on salaries and guaranteeing a committed, if temporary, workforce, the traditions of apprenticeship would have allowed the board to exert control over all elements of young teachers’ lives. As was common in apprenticeship agreements, the FSS indenture agreement forbade apprentices from having sex, getting married, gambling, drinking, or attending plays. Most important, the agreement legally prohibited apprentices from leaving.

In exchange, the FSS offered food, housing, and clean clothes. When the apprentice teachers aged out, they would be granted a leaving bonus—a parting gift of cash, with the amount to be determined later by the FSS.

Temporary enslavement like this might seem shocking these days, but it had been a common practice among teachers in England. In 1813, for instance, Joseph Lancaster took on young men—never women—to serve as his teaching apprentices in his thriving London school.

As was common in apprenticeship systems, parents often heartily supported the “masters.” One father told his grumbling son and Joseph Lancaster in 1813,

Your master may dispose of you in any way he pleases—he has my hearty concurrence beg leave again to repeat—Sir do with my Child as you see fit my liberty and blessing you have For ever.

The power to deal with instructional staff in any way they pleased was enormously tempting for New York’s early school leaders. In the end, however, New York’s FSS trustees decided against turning their employees into apprentices. They realized that their young teachers would not likely accept the plan and could veto it, in practice, by simply walking out.

The lessons of the early 1800s resonate with our teacher-pay politics today. The pressures on any school budget have always been intense. There is never enough money for every program and every need. When underpaid teachers threaten to walk away, school leaders have always considered desperate plans to fix desperate financial problems.

For more by this author, check out his latest book: