Abraham Lincoln, Joe Biden and the politics of touch

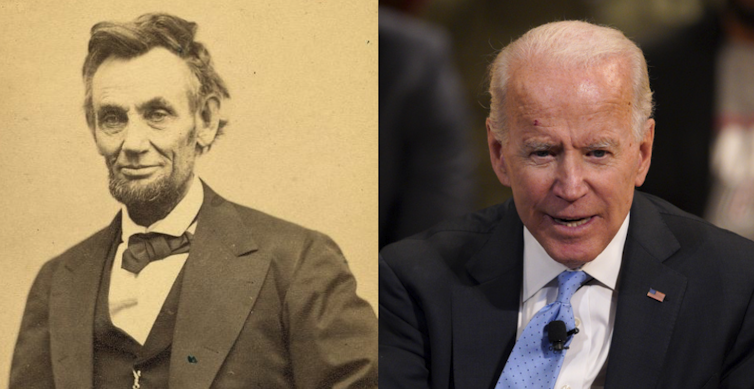

President Abraham Lincoln in 1865 and Vice President Joseph Biden in 2019. Library of Congress, photo Alexander Gardner; AP/Nati Harnik

Mark M. Smith, University of South Carolina

Amidst the furor over former Vice President Biden’s handsy habits – and with examples of inappropriate touching by current and former U.S. presidents still lingering – it might be a good time to recall how past politicians learned to use touch not to molest, intimidate or cow but to connect, engage and inspire.

No one was better at tactile politics than Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln lived in a time when American political culture valued touch. Handshaking had long been important as a sign of political and social etiquette.

Quakers, for example, preferred the handshake over doffing hats and bowing because the act had something of a democratic ring to it, denoting a rough equality.

By the early 19th century, handshaking was becoming both more American and masculine. French and British gentlemen were less inclined to shake hands and considered the American habit of sweaty handshaking “disgusting.”

Lincoln and American politicians cast their touch as a necessary part of political culture and engagement.

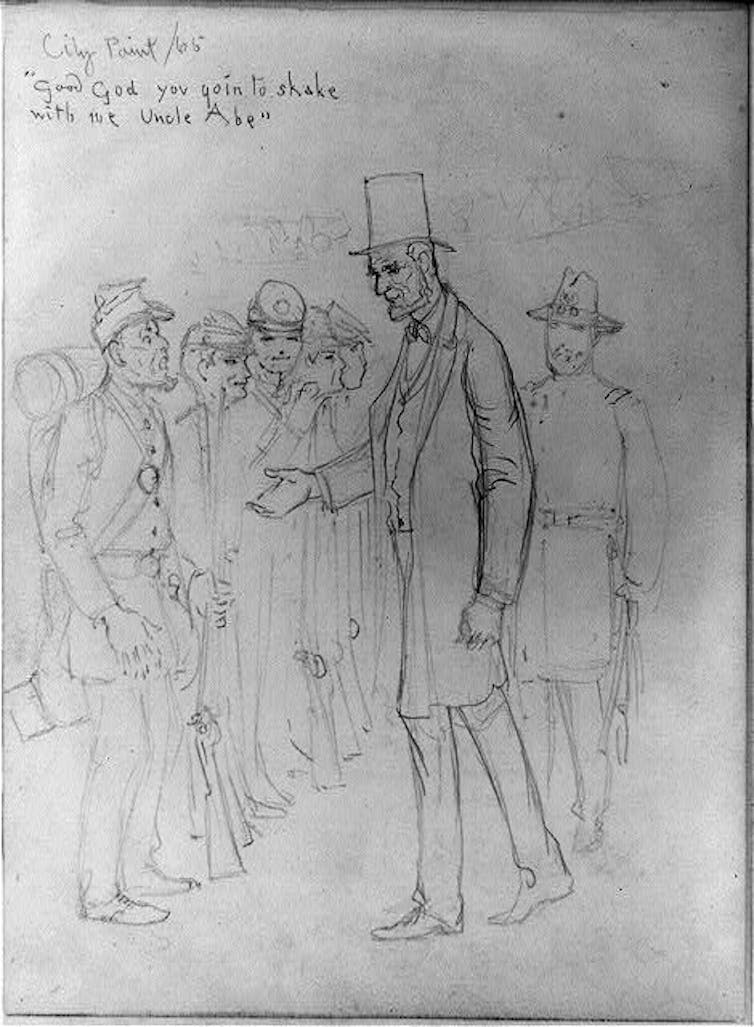

A drawing of Abraham Lincoln offering his hand to a Union soldier, City Point, Virginia. Library of Congress, drawing by Charles W. Reed

I’m a scholar of sensory history, and in my research I have found that elected and electable leaders during the 19th century especially had to touch voters, metaphorically and literally, a point Lincoln probably learned while glad-handing as a young traveling lawyer.

Right and wrong way

Then, as now, how you touched someone was politically risky. In the cultural and political ritual of American handshaking, care had to be taken not to slight or send the wrong message.

An essay entitled “Hand-Shaking,” from Harper’s Weekly of May 21, 1870, declared that refusing to shake hands was a “declaration of hostility,” but pressing the flesh had to be done with care.

Too tight a grip, the essay continued, indicated “tyranny,” a product of either unwitting strength or malicious intent. More “odious” was “he who offers you his hand, but will not permit you to get fair hold of it.” Such tactile diffidence reflected “cool contempt or supercilious scorn.”

Lincoln was a prodigious handshaker, and it added to his reputation as an egalitarian, common man, one literally and figuratively in touch with the people.

A marathon handshaking session in New York in February 1861 as president-elect left him with hurt hands. Just after his election as president, according to J. G. Holland in 1866, Lincoln met with crowds whose “hand-shaking … was something fearful” with “Every man in the crowd … anxious to wrench the hand of Abraham Lincoln. He finally gave both hands to the work, with great good nature.”

Plaster casts of Lincoln’s hands, made by Leonard Volk in May 1860. Smithsonian National Museum of American History

‘Shaky signature’

Lincoln’s hands were imprinted with politics, with key initiatives written into and onto his skin. According to Massachusetts Sen. Charles Sumner, even Lincoln’s signature on the Emancipation Proclamation was riddled with the common touch because “he had been shaking hands all the morning, so that his writing was unsteady.”

Lincoln commented: “When people see that shaky signature they will say ‘See how uncertain he was.’ But I was never surer of anything in my life.”

The only cast of Lincoln’s hands, taken by Leonard W. Volk in Springfield, Illinois on the Sunday after Lincoln’s nomination in 1860, is deeply inscribed with a history of handshaking.

Volk made the cast after “thousands” had gone to Lincoln’s home, “passing through the house in single file, each citizen giving Lincoln a vigorous handshake.”

The cast tells the story of touch: “The swollen muscles that resulted from this reception are quite noticeable in the cast,” said essayist Laurence Hutton, who owned it.

It’s important to note that Lincoln not only used touch to connect with voters – as politicians still do – but that he did so within widely accepted rules – as some politicians no longer do.

Unlike Biden, Lincoln was no hugger, sniffer or caresser for the simple reason that those tactile and olfactory displays were wholly inappropriate among white men of the time.

But for Lincoln, those rules were no impediment.

Lincoln used the simple handshake to help engage a nation and guide it through an immensely difficult time of war and national upheaval. That’s a reminder that appropriate touching plays an important role in American political culture.

Mark M. Smith, Carolina Distinguished Professor of History, University of South Carolina

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.