Clarence Thomas is Wrong: It’s Restrictions on Abortion that Echo America’s Eugenics Past

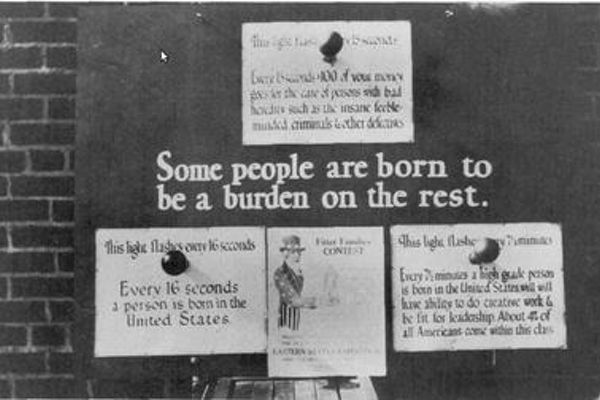

U.S. eugenics poster advocating for the removal of genetic "defectives" c. 1926

In the last few months, five states have enacted harsh new laws that place severe restrictions on abortion and are intended to provoke a legal challenge to overturn Roe v. Wade. Georgia, Mississippi and Ohio would ban abortion as early as the sixth week of pregnancy, when physicians can detect a “heartbeat” but before many women know they are pregnant. Alabama would make performing or attempting to perform an abortion a felony unless the mother’s life is at risk—without any exceptions for rape and incest. This week, in a Supreme Court decision upholding part of Indiana’s abortion law, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote a 20-page concurring opinion that asserts “a State’s compelling interest in preventing abortion from becoming a tool of modern-day eugenics” by drawing on history. Thomas is wrong. It is not women’s right to choose abortion but the new state laws restricting abortion that are an echo of America’s eugenics past.

Between 1907 and 1937, thirty-two states passed laws permitting state officials to remove the reproductive abilities of individuals designated “feebleminded” or mentally ill in order to improve the human population. By the 1970s, more than 63,000 Americans—60 percent of them women—were sterilized as a result of these laws. In the first decades of legal sterilization, eugenic sterilization was controversial and a number of state laws were struck down in court. Then in 1927, the US Supreme Court upheld Virginia’s eugenic sterilization law in an 8-1 decision. Using language astonishing for its cruelty, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. affirmed the state’s power to prevent those who were “manifestly unfit from continuing their kind,” adding that “three generations of imbeciles are enough.” Buck v. Bell established the constitutionality of state-authorized sterilization for eugenic purposes, and it has never been overturned.

Opponents of abortion rights like to emphasize the eugenic roots of birth control and abortion, especially the role of Margaret Sanger and Planned Parenthood. The “heartbeat” laws do not explicitly mention eugenics, but the Alabama law actually likens abortion to the murder of Jews in the Holocaust and other 20th century genocides. It also compares the defense of the “unborn child” to the anti-slavery and woman suffrage movements, the Nuremberg war crimes trial, and the American civil rights movement.

These comparisons present a serious misunderstanding of American history and eugenics. State sterilization laws generally had bipartisan support and were more varied—and more rooted in local politics and welfare systems-- than abortion opponents suggest. Despite some eugenicists’ mean-spirited rants about the menace of the unfit, many also described involuntary sterilization as, in the words of California Republican Paul Popenoe, a “protection, not a penalty.” Sterilization would “protect” the unfit from the burden of childrearing and protect the unborn from being raised by incompetent parents.

Eugenic ideas echo in the anti-abortion movement today. Like sterilization crusaders in the past, abortion foes see private decisions about reproduction as an urgent matter of state concern. They justify their interventions using dubious science—crude theories of human heredity in the eugenics case, and, to use the Georgia law as an example, inaccurate claims that “modern medical science, not available decades ago” proves that fetuses are living persons who experience pain and should be recognized in law. Moreover, the logic behind abortion restrictions, like eugenic sterilization, is deeply evaluative: some lives have more value than others. Low-income women and women of color will be hardest hit by an abortion ban, and the fetus is accorded more value than a pregnant woman.

State sterilization laws, too, targeted the most disadvantaged members of society. Young women who became pregnant outside of marriage; welfare recipients with several children; people with disabilities or mental illness—as well as immigrants, people of color, and poor rural whites—were at risk of being designated “feebleminded” or “insane” and sterilized under eugenics laws. Survivors of rape, incest, or other types of trauma (like institutionalization) were especially vulnerable. Carrie Buck, whose 1927 sterilization was authorized by the Supreme Court, became pregnant at age seventeen after being raped by a relative of her foster parents. They responded to her ordeal by petitioning a local court to commit her to the Virginia Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-minded. As an added indignity, they also took Carrie’s daughter and raised her as their own. Forty years later, North Carolina sterilized Elaine Riddick Jessie, a fourteen-year old African American girl social workers considered promiscuous and feebleminded because she became pregnant as the result of rape by an older man. Buck’s and Jessie’s stories are just the tip of the iceberg, rare public accounts of shame and suffering that have mostly remained private. Indeed, about one-third of all those for whom the North Carolina Eugenics Board authorized eugenic sterilization were minors – some as young as 11. The vast majority were victims of rape or incest.

Memories of eugenic sterilization have focused almost exclusively on race, class, and the American eugenics movement’s connection to Nazi Germany. Yet these are selective memories that sever forced sterilization from the issue of reproductive rights. In fact, coerced sterilization proliferated when sex education, birth control, and abortion were illegal or inaccessible to women and girls who were poor. The women most likely to become victims of state sterilization programs were those who lacked access to reproductive health care. Tragically, our research shows that some poor women with large families actually sought “eugenic” sterilization because they had no other way of ending unwanted pregnancies.

The animating belief of eugenics—the state should control the reproduction of poor people, immigrants, and women of color—is central to current abortion politics. It is hardly a coincidence that Alabama’s new abortion law permits no exception for rape and incest and imposes harsher penalties on the doctors who perform abortions than on rapists, but the state still refuses to expand access to Medicaid or take steps to bring down the state’s infant mortality rate, the second highest in the nation. The double violation at the core of Alabama’s abortion restrictions—discounting the pain of sexual violence and elevating the fetus over the pregnant women--perpetuates the dehumanizing logic of eugenics.

Still, it is crucial to remember the significant differences between the current fight over abortion and America’s eugenics past. State sterilization laws once had bipartisan support from Republicans and Democrats, and no social movement ever arose to contest them. In contrast, Republican-led efforts to recriminalize abortion are rigidly partisan, and a movement to defend the reproductive and human rights of pregnant women is rising.