Stonewall's Legacy and Kwame Anthony Appiah's Misuse of History

In a recent op-ed in the New York Times, “Stonewall and the Myth of Self-Deliverance (June 22, 2019) Kwame Anthony Appiah, a distinguished philosopher at Columbia University, tries to debunk what he considers a myth: that the 1969 Stonewall Rebellion led to the takeoff of the Gay Rights movement in the United States. Instead, he credits “black-robed heterosexuals” (judges) who made important legal decisions and “mainstream politicians” who jumped on the gay rights bandwagon decades after Stonewall. In Appiah’s philosophy, long-term abusers who finally recant and mainstream political figures that drew them into coalitions, not the people whose actions created crises and precipitated change, deserve credit for marginalized groups gaining basic human rights.

Curiously, much of Appiah’s argument rests on events in Great Britain rather than the United States, events that he does not completely or accurately report. Appiah’s hero is Leo Abse, a backbench Labour Member of Parliament who pushed a private member bill that Appiah claims, “basically decriminalized homosexuality.” The Sexual Offences Act of 1967 revised a 1553 Buggery Act that made male same-sex sexual activity punishable by death and an 1885 law that eliminated the death penalty but maintained criminality.

What Appiah ignores in his claims is the lead up to passage of the 1967 act and the limits of the act itself. In the Cold War climate of the early 1950s, British police were actively enforcing laws prohibiting male homosexuality, partly out of concern with national security and partly as part of rightwing anti-communist crusades. A series of high-profile arrests and show trials, including prominent members of the British elite, led to imprisonment and in the case of Alan Turing, a scientist and World War II hero, enforced chemical castration and suicide. Reaction to the anti-homosexual campaign led to the 1957 Wolfden Report that recommended the decriminalization of homosexuality. However it was not until 1967 when the Labour Party took power that the recommendations were implemented. Abse was credited with the bill so Labour Party leadership could distance themselves from accusations that they were pro-gay.

Appiah also missed that the Sexual Offences Act maintained general prohibitions against “buggery” and indecency between men, and only provided for a limited decriminalization when sexual relations took place in the privacy of someone’s home. It was still criminal if men had sexual relations in a hotel or if one of the parties was under age 21.

Appiah is correct that individual acts of defiance, by themselves, do not generate major institutional change. Rosa Parks was not a little old lady who refused to give up her seat on a bus because she was tired. Parks was part of organized resistance to bus segregation by the local NAACP and a coalition of Montgomery’s Black churches.

What Appiah misses in his dismissal of the Stonewall Rebellion’s historical importance is that symbols like Rosa Parks sitting down and Stonewall are crucial to social movements as they mobilize and move from the political margins to the center of civic discourse. In the 1850s, the Underground Railroad was both an important symbol for Northern abolitionists demanding an end to slavery because it demonstrated the enslaved Africans desire for freedom whatever the risk and for Southern slaveholders demanding constitutional protection for their “property” rights. John Brown was executed for his role in the 1859 raid on the federal armory in Harpers Ferry. Two years later, United States troops marched into battle against the Confederacy singing that while Brown’s body is “moldering in the grave, his soul’s marching on.”

Appiah’s argument is indicative of his larger philosophical outlook. As I read his philosophical work, Appiah tends toward Hegelian idealism, the belief that abstract ideas somehow play an independent and dominant role in shaping history. In New York Times Magazine advice columns his tendency is to recommend a hands-off or non-interventionist approach to personal moral dilemmas. Politically, Appiah places his hopes for change on persuasion and rejects intervention.

In his book The Honor Code, How Moral Revolutions Happen (Norton, 2010), Appiah credited British commitment to the idea of “honor” for the end of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and slavery in the British colonial empire. Missing from the book are any references to Toussaint Loverture and Sam Sharpe, leaders of slave rebellions in Haiti and Jamaica that shook the colonial world and were instrumental in ending slavery. Paradoxically, Appiah managed to attribute honor and idealism to 19th century British leaders, the same people who were busy colonizing India and Africa and marketing opium in China, while ignoring famine in Ireland and exploiting and impoverishing its own working class.

But Appiah’s argument doesn’t end with how history is written: it’s also about how history is taught. As a teacher and teacher educator I was disturbed by Appiah’s dismissal of the way the “great moral crusade of the 19th century, is now taught in schools.” He cites the “New York State Regents curriculum guide, which shapes public high school education in the state,” especially its reference to “people who took action to abolish slavery” that “names four individuals, all but one of them people of color.”

While Appiah is worried about what he considers a misleading high school curriculum, he is actually quoting from the 4th grade New York State Regents standard (4.5) for teaching about slavery. It focuses on the biographies of individuals with connections to New York and includes Samuel Cornish (New York City), Frederick Douglass (Rochester), and Harriet Tubman (Auburn). It also introduces students to William Lloyd Garrison, a white, non-New York abolitionist. The focus on biography may be simplistic, it is fourth grade after all and the children are ten-years old.

The high school standards, which like the 4th grade standards are advisory, not mandatory, are very different. They recommend that students “analyze slavery as a deeply established component of the colonial economic system and social structure, indentured servitude vs. slavery, the increased concentration of slaves in the South, and the development of slavery as a racial institution” (11.1); “explore the development of the Constitution, including the major debates and their resolutions, which included compromises over representation, taxation, and slavery” (11.2c); “investigate the development of the abolitionist movement, focusing on Nat Turner’s Rebellion, Sojourner Truth, William Lloyd Garrison (The Liberator), Frederick Douglass (The Autobiography of Frederick Douglass and The North Star), and Harriet Beecher Stowe (Uncle Tom’s Cabin)” (11.3b); and recognize that “Long-standing disputes over States rights and slavery and the secession of Southern states from the Union, sparked by the election of Abraham Lincoln, led to the Civil War. After the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing the slaves became a major Union goal” (11.3c).

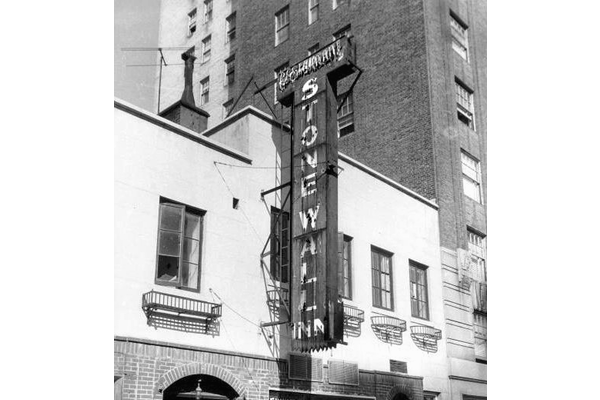

Standard 11.10b focuses on how “Individuals, diverse groups, and organizations have sought to bring about change in American society through a variety of methods.” It includes “Gay Rights and the LGBT movement (e.g., Stonewall Inn riots [1969]” efforts to achieve equal legal rights. In addition, in the 12th grade civics curriculum (12.G2d), students learn that “the definition of civil rights has broadened over the course of United States history, and the number of people and groups legally ensured of these rights has also expanded. However, the degree to which rights extend equally and fairly to all (e.g., race, class, gender, sexual orientation) is a continued source of civic contention.”

The New York Times should have done a better job fact-checking Appiah’s essay. Philosophy may be allegorical. History definitely isn’t.