The Case for Religious Progressivism

A recent article in The Washington Post dealing with Democratic candidate Pete Buttigieg’s religious beliefs argues that “American progressivism, for all that is good about it, is no more Christian than political conservatism.” Disagreeing with that perspective, the following essay asserts the value of religious progressivism—not as the only valid type of progressivism, but rather as one vital contributor to it. Progressivism should be “a big tent,” welcoming people of all races, spiritual beliefs (including atheistic humanism), classes, and sexual preferences, united by the conviction that free-market capitalism is not a sufficient public philosophy. A higher goal, seeking the common good, must take precedence and oversee our economic system.

“Religious progressivism” here means a progressivism motivated by values that have long been championed by the world’s major religions—love, wisdom, compassion, empathy, humility, patience, prudence, and self-discipline. Other important values (or virtues), such as tolerance, have sometimes been undervalued by those considering themselves religious, but one can argue (as I do here) that it should flow naturally from love and humility. The same can be said for another value, a sense of humor. The leading American religious thinker of the twentieth century, the Protestant Reinhold Niebuhr, believed that the ability to laugh at oneself reflected humility and is “a prelude to faith; and laughter is the beginning of prayer.”

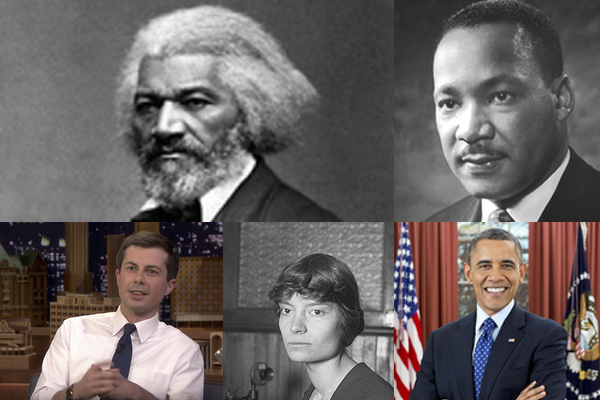

Although progressivism as a political movement did not manifest itself in the USA until the final decade of the nineteenth century, progressive thinking appeared much earlier and was sometimes linked with religious beliefs. One outstanding example was that of Frederick Douglass.

Today many who call themselves religiousare critical of progressive positions. After all, 81 percent of white evangelicals supported Trump in the 2016 presidential election. But their Christianity differs profoundly from that of someone like the abolitionist Douglass, whom Barack Obama identified as one of America’s five great reformers who “not only were motivated by faith but repeatedly used religious language to argue their causes.”

In one of his great speeches, given in 1852, Douglass, blasted most U. S. Christian churches for being “not only indifferent to the wrongs of the slave,” but actually taking “sides with the oppressors.” Many of Christianity’s “most eloquent” leaders, he charged, “have shamelessly given the sanction of religion and the Bible to the whole slave system.” Their “horrible blasphemy is palmed off upon the world for Christianity.” For his part, however, he “would say, welcome infidelity! welcome atheism! welcome anything! in preference to the gospel, as preached” by those leaders.

Yet, as D. H. Dilbeck has recently demonstrated, this man who said “welcome atheism!” adhered to a Christianity that “shaped his public career,” and was “vital to understanding who he was, how he thought, and what he did.”

By the time of Douglass’s death in 1895, the Progressive Era (1890-1914) had begun. One reliable historical work describes Progressivism as a diverse movement “to limit the socially destructive effects of morally unhindered capitalism, to extract from those [capitalist] markets the tasks they had demonstrably bungled, to counterbalance the markets’ atomizing social effects with a countercalculus of the public weal [well-being].” It did not attempt to overthrow or replace capitalism, but to have government bodies and laws constrain and supplement it in order to insure that it served the public good.

Progressives worked to produce a graduated federal income tax, to reduce corruption in city governments, limit trusts and monopolies, expand public services, and pass laws improving sanitation, education, housing, and workers’ rights and conditions, especially for women and children. Progressive efforts also helped pass pure food and drug laws and create the National Park Service. Some Progressives like Jane Addams, who in 1889 established Chicago’s Hull House to aid the poor, also worked hard to secure the vote for women, which was not achieved in presidential elections until 1920. Following three Republicans in the following dozen years, Franklin Roosevelt renewed the Progressive tradition.

Historian Jill Lepore writes, “Much that was vital in Progressivism grew out of Protestantism, and especially out of a movement known as the Social Gospel, adopted by almost all theological liberals and by a large number of theological conservatives, too.” They argued that “fighting inequality produced by industrialism was an obligation of Christians. . . . Social Gospelers brought the zeal of abolitionism to the problem of industrialism.”

Outside of the United States, Christians also occasionally interpreted the message of Jesus in a liberal or socialist manner. Two examples were the French Catholic priest Félicité Lamennais (1782-1854), who broke with his church, and the Russian ecumenical thinker Vladimir Soloviev (1853-1900), a prominent lay theologian and philosopher who allied with Russian liberals against Russian Orthodox conservatives.

Back in the United States, the tradition of a radical leftist Christianity continued during the FDR years and beyond with the work of Dorothy Day (1897-1980). A convert to Catholicism, she was praised by Pope Francis in his 2015 Address to the U. S. Congress: “In these times when social concerns are so important, I cannot fail to mention the Servant of God Dorothy Day, who founded the Catholic Worker Movement. Her social activism, her passion for justice and for the cause of the oppressed, were inspired by the Gospel, her faith, and the example of the saints.” Earlier, in his The Audacity of Hope (2006), future President Obama had identified her—along with Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, William Jennings Bryan, and Martin Luther King, Jr.—as one of America’s “great reformers” that was motivated by religious faith. A pacifist who also identified with non-violent anarchism, Day was profoundly influenced by her Catholic beliefs.

But her Catholicism was not of the narrow, dogmatic sort but one appreciative of ecumenical outreach. She once wrote that “there is no public figure who has more conformed his life to the life of Jesus Christ than Gandhi”—another twentieth figure whose political philosophy was strongly indebted to spiritual beliefs. Day greatly admired him for advocating spiritual means of resisting violence and injustice. She also wrote of seeing Christ in some anarchists “because they are giving themselves to working for a better social order for the wretched of the earth.”

Day was often arrested for protesting. In 1974, she mentioned that she had “been behind bars in police stations, houses of detention, jails and prison farms, whatsoever they are called, eleven times.” Her last arrest, in 1973, was for “unlawful assembly,” in the midst of picketing in behalf of the itinerant Mexican workers of the United Farm Workers led by her friend Cesar Chavez, another Catholic whose protests were fueled by his religious beliefs. During the 1960s Day sometimes picketed and spoke in behalf of civil rights, and she greatly admired Martin Luther King, Jr. (MLK), whom she referred to as “a man of the deepest and most profound spiritual insights.”

MLK, of course, was a Baptist minister, who had received his Ph.D. from Boston University’s School of Theology. As a student he had been strongly influenced by the early twentieth-century Social Gospel movement and throughout his life by Gandhi, who King considered “probably the first person in history to lift the love ethic of Jesus above mere interaction between individuals to a powerful effective social force on a large scale.” (Christian liberation theology, developed in Latin America in the mid-20th century, was another influence on MLK.) The Gandhian mass non-violent resistance tactics that he developed were to be “based on the principle of love.”

The whole civil rights movement of the late 1950s and 1960s was spurred on by religious principles. To help lead it, King and others (many black ministers) formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and he was its first president. In addition, King’s demonstration marches “brought together people . . . from widely differing church traditions, not only Christians but also Jews and humanists.”

In our own day, Barack Obama has been one of the strongest proponents of a religious progressivism. His The Audacity of Hope contains a long chapter on “Faith.” In it the future president wrote, “Surely, secularists are wrong when they ask believers to leave their religion at the door before entering the public square.” He discussed his own path to religious faith, culminating in his baptism at the Trinity United Church of Chicago. And he stated that “if we progressives shed some of our own biases, we might recognize the values that both religious and secular people share when it comes to the moral and material direction of our country, and that such values could help lead to “the larger project of American renewal.” After becoming president, Obama continued to make the case for Christians pursuing a progressive approach.

A leader whose tenure began about the same time as Obama’s second term, Pope Francis, also often advocated a religious progressivism on such issues as the flaws of capitalism and environmental responsibility. And like Obama, he has warned against ideological rigidity—“In a 2013 sermon he warned Christians against making their religion into an ideology: “When a Christian becomes a disciple of the ideology, he has lost the faith. . . . But it is a serious illness, this of ideological Christians. . . . [It is too] rigid, moralistic, ethical, but without kindness.”

Thus, those who argue, “We should keep religion out of politics,” are being simplistic. One can more properly cite individuals like Frederick Douglass, Dorothy Day, Martin Luther King Jr., Barack Obama, and Pope Francis who counter that the spiritual and moral values commonly advocated by major religions should inspire our politics.