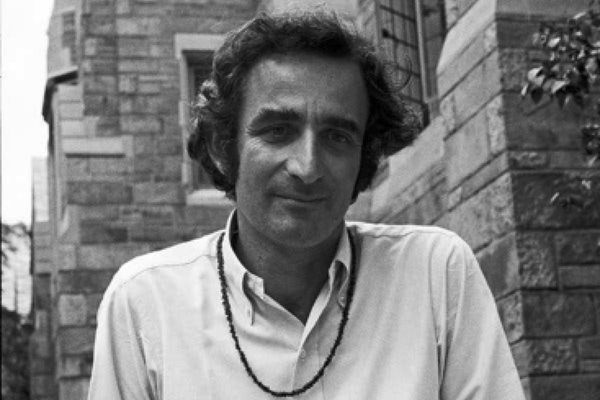

Charles Reich and The Greening of America – an Appreciation

Charles Reich, author of The Greening of America, passed away last month at the age of 91.

His book was first published in 1970 to mixed reviews: Newsweek’s Stewart Alsop called it “scary mush.” Another critic labeled it “a toasted marshmallow,” devoid of substance. Yet Reich’s book, a combination of history, sociology and philosophy struck a chord in a somber time of war and national protest. It went on to sell five million copies and become a key cultural anchoring point, a book that explained the new counterculture in a clear, uplifting manner.

In 1970, I was one of the legions of long-haired, dope-smoking, anti-war protesting college students. We knew what we were against, but were struggling to define a vision of the future. Like many of my friends, I devoured Reich’s book, underlining dozens of passages. The Greening of America became a touchstone for our generation, the center of many intense conversations in campus cafeterias and smoke-filled dorm rooms. We were angered by Nixon’s deceitful actions to prolong the Vietnam war, distrustful of a soul-crushing corporate culture and curious about the promise of new technology (NASA landed on the moon in 1969, but an affordable personal computer was still a decade away).

The Greening of America spoke to our concerns with a carefully reasoned, historically anchored thesis. It explained many of the hopes and fears we felt intuitively but had not been able to articulate at length.

Rather than talking about a violent political revolution, Reich described a revolution based on a new, open culture that freed men’s minds, not repressed them. He described an America that had evolved since the 1776 Revolution through three “consciousnesses.” In the first hundred years, Consciousness I, based on individual freedom and self-reliance, spurred the settling of the new nation. Consciousness II, born with the rise of industrial society in the 19th century, created a new hierarchy and demanded submission of an individual’s identity to the corporation. The rise of a mass consumer culture defined happiness in the terms of a man’s position in a hierarchy of status. Factories and workshops produced a split between the duties and identity of “man at home” versus the “man at work.”

According to Reich, the post-World War II boom brought new economic security and allowed the first stirrings of Consciousness III to emerge among the children of a new, expanded middle-class. Many members of this generation sought to gain a new freedom based on a “lifestyle” that was authentic. Their identity was based on cultural interests, creativity and self-expression, not status-seeking through the accumulation of consumer goods.

One of the joys of Reich’s book was its optimism; one reviewer noted “It combined the rigor of an intellectual and the enthusiasm of a teenager.”

Greening was based on the belief that America had been founded with great hopes for personal freedom and that its Constitution allowed for major societal change. As Reich saw it, “there is a revolution underway. If it succeeds it will change the political structure as its final act. It will not require violence to succeed. Its ultimate creation could be a higher reason, a more human community and a new and liberated individual.”

1950s Social Criticism

Reich’s book did not appear in a vacuum. Concern about the domination of large corporations in culture and politics and the loss of individual identity has been brewing for some time. David Riesman’s The Lonely Crowd, a critique of the new suburban culture, appeared in 1950. In 1964, Herbert Marcuse, a philosophy professor at UC San Diego, published One Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society. Marcuse’s book contained scores of profound insights, but it was written at the level of a philosophy textbook. It contained numerous references to Marx, Hegel, Max Weber, Walter Benjamin and other German scholars. While we loved the title, One Dimensional Man was simply beyond the comprehension of most undergraduates.

For college students today, the word “greening” today is closely associated with the environmental movement (green buildings, a Green New Deal), but Reich’s book barely touched on the environment. For him, greening meant newness, a natural growth. He compared the emerging youth culture to like “flowers poking up through the concrete.”

Reich wrote in 1970, before the 1973 oil embargo, when gasoline was around 30 cents per gallon and solar power was so expensive it was used only on NASA space probes. The rainforests were still intact and global warming had yet to manifest itself.

Greening did not meet with universal acclaim. Critics on the far left, including Herbert Marcuse, condemned it for being “naïve,” and imaging that massive social change was possible without violent action. Marcuse, in a critique published in the New York Times in November 1970 warned that no national revolution has ever succeeded without violence. Marcuse advised that the entrenched “groups, classes, interests” in America controlled the police and armed forces. They set the priorities for America and they would not voluntarily give up any of their power.

Reading Reich’s book today, some fifty years after its publication, we can see that many of the descriptions of the descriptions of repressive culture accompanying Consciousness are still valid. But his predictions about an emerging Consciousness III were off-target.

From today’s vantage point, it is clear this book was written by an affluent white man working at an elite cultural institution and for an audience of well-educated young white people. Although Reich included a few quotes from Eldridge Cleaver’s recently published Soul on Ice, he never discussed the crushing poverty of inner-city ghettos, the suburbs’ segregated schools nor the structural racism still in place in the 1960s.

He also seemed blind to the nascent feminist movement. Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique was published in 1963 and the National Organization for Women founded in 1966, so the basic tenets of feminism were known, if not yet widely practices. His vision for Consciousness III women was confined to “liberated housewives” and enlightened school teachers.

Still, Reich was eerily prescient about many other trends in American society. In Greening he posited that “the great question of these times is how to live in and with a technological society; what mind and what way of life can preserve man’s humanity against the domination of the forces he has created.”

He also warned of “the willful ignorance in American life.” He lamented that Americans “could be sold an ignorant and incapable leader because he looked like the embodiment of American virtues.”

Reich left Yale Law School in 1974 and moved to San Francisco. He published several more books, including an autobiography, The Sorcerer of Bolinas Reef, in which he revealed his gay identity.

Reich gave the younger generation hope in a dark period in American history. He will be missed.

Note: Although the original 120,000-word edition of Greening of America is out of print, a condensed, 25,000 e-book version, with a new forward by Charles Reich, was published in 2012 and is available on the Internet.