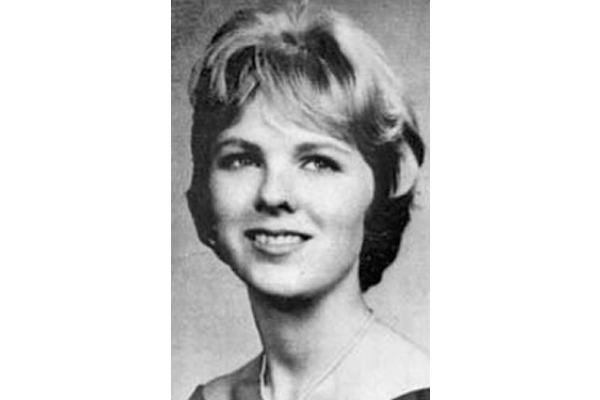

Mary Jo Kopechne’s Legacy

On July 19, 1969, Senator Edward M. Kennedy drove his black Oldsmobile off a bridge on Chappaquiddick Island, near Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts. His 28-year-old passenger, Mary Jo Kopechne, was killed in the accident.

A week later, Kennedy went on national television to ask the people of Massachusetts for their forgiveness. And they forgave him each of the six times he was reelected to the Senate until his death from brain cancer in 2009. History has not been as kind to Kopechne.

For fifty years, Mary Jo was treated as collateral damage by the Kennedys and the Washington political establishment. The media spun the tragedy as part of a much larger “curse” on the Kennedy family, and one that prevented the Massachusetts senator from being elected to the presidency. Other, more sensationalist writers suggested that Kopechne was an opportunist who was having an affair with the senator.

But Kopechne’s life and legacy are much greater than her death at Chappaquiddick and the cottage industry of scandalous accounts that followed over the next half century. Mary Jo was a bright young woman who was a pioneer for a later generation of female political consultants, including Mary Matalin, Ann Erben and Donna Lucas.

Inspired by President John F. Kennedy's challenge to "ask what you can do for your country," Mary Jo Kopechne became part of the civil rights movement, taking a job as a school teacher at the Mission of St. Jude in Montgomery, Ala. Three years later, she joined the Capitol Hill staff of New York Sen. Robert F. Kennedy.

A devout Catholic, Kopechne lived in a Georgetown neighborhood with three other women. She rarely drank, didn’t smoke and was offended by profanity, yet she was irresistibly drawn to the fast-paced, glitzy world of Washington.

Mary Jo distinguished herself during RFK’s by working long hours at his Washington headquarters. During Bobby’s 1968 presidential campaign, Kopechne served as a secretary to speechwriters Jeff Greenfield, Peter Edelman and Adam Walinsky and tracked and compiled data on how Democratic delegates from various states might vote. She shared the latter responsibility with five other young women: Rosemary Keough, Esther Newberg, Nance and Maryellen Lyons, and Susan Tannenbaum. Collectively, they were known as the "Boiler Room Girls,” after the windowless office they worked in at 2020 L Street in Washington, DC.

At age 27, Mary Jo was the oldest of the Boiler Room Girls and the one who had worked for RFK the longest. She was the key Washington contact in the Boiler Room. She also kept track of delegates in Indiana, Kentucky and Pennsylvania, critical battleground states where polls were predicting a close race between Kennedy and Vice-President Hubert Humphrey.

Mary Jo was only paid $6,000 a year when she was hired, compared to the male legislative assistants who started at a salary of between $12,000 and $15,000 a year. In the four years she worked for RFK she never earned more than $7,500 a year; enough to pay rent and maintain a Volkswagen Beetle.

By today’s standards, Kopechne was grossly underpaid, extremely overworked and dismissed as a “secretary” when her responsibilities demanded the more respectable title of “political consultant” and paid accordingly. But she belonged to a transitional generation of women who paved the way for the feminists of the 1970s and their fight for gender equality.

Of all the Boiler Room Girls, Kopechne was the “the most politically astute,” according to Dun Gifford, who supervised the operation. “Mary Jo had an exceptional ability to stay ahead of fluctuating intelligence on delegates. That ability allowed her to negotiate deals on RFK’s behalf, to travel with him when necessary and even to offer her opinions when she had the best working knowledge of a situation.

“Had Bobby won the election, Mary Jo would have been rewarded with a very significant job in his administration,” added Gifford. Kopechne was devastated by RFK's assassination in June 1968, and she felt she could no longer work on Capitol Hill. Instead, she took a job with a political consulting firm in Washington, D.C.

On the evening of July 18, 1969, Mary Jo attended a party thrown by Ted Kennedy on Chappaquiddick to honor her and the other Boiler Room Girls. Later that night, she accepted the senator's offer to drive her back to her hotel on Martha’s Vineyard. Kennedy's car swerved off a narrow, unlit bridge and overturned in the water. The senator escaped from the submerged car, but Kopechne died after what Kennedy claimed were "several diving attempts to free her."

By the time Kennedy reported the accident to police the following morning, Kopechne's body had been recovered. John Farrar, the diver who found her, reported that she had positioned herself near a backseat wheel well, where an air pocket had formed, and had apparently suffocated rather than drowned. Farrar added that he "could have saved her life if the accident had been reported earlier." Kennedy could easily have been charged with involuntary homicide and sentenced to significant jail time for Kopechne's death. Judge James Boyle instead sentenced him to two months' incarceration, the statutory minimum for the crime. He then suspended the sentence saying that Kennedy had "already been, and will continue to be, punished far beyond anything this court can impose."

Perhaps Ted Kennedy tried to do his penance in the United States Senate, where he championed historic legislation on civil rights, immigration, education, and health care.

If so, Mary Jo Kopechne inspired those achievements because her death forced the embattled senator to strive for a higher standard.