The Beginning of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic – and One Doctor's Search for a Cure

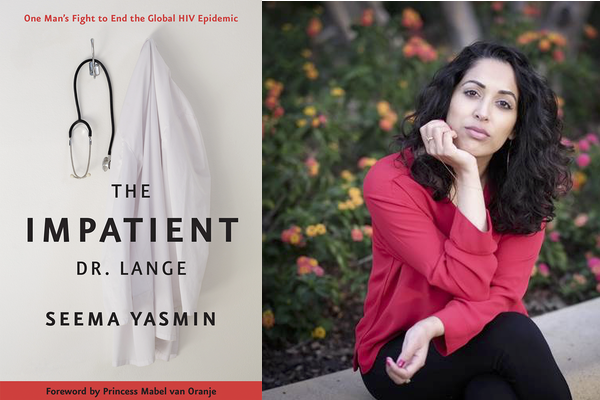

The following is an excerpt from The Impatient Dr. Lange by Dr. Seems Yasmin.

Before the living dead roamed the hospital, the sharp angles of their bones poking through paper-thin bed sheets and diaphanous nightgowns, there was one patient, a harbinger of what would consume the rest of Dr. Joep’s life. Noah walked into the hospital on the last Sunday in November of 1981. It was Joep’s sixth month as a doctor and a quiet day in the emergency room at the Wilhelmina hospital, a red brick building surrounded by gardens in the center of Amsterdam.

Noah was forty-two years old, feverish, and pale. His skin dripped a cold sweat. The insides of his cheeks were fuzzy with thick streaks of white fungus. And then there was the diarrhea. Relentless, bloody diar- rhea. Noah’s stomach cramped, his sides ached, he couldn’t swallow food. Doctors admitted him to the infectious disease ward, a former army barracks in the ninety-year-old hospital, where they puzzled over the streaky plaques of Candida albicans, a yeasty fungus growing inside his mouth, and the bacteria Shigella breeding inside his gut.

Noah swallowed spoonfuls of antifungal medicine. Antibiotics were pushed through his veins until his mouth turned a rosy pink and his bowels quieted. Still, the doctors were baffled by his unlikely conglomeration of symptoms. “The patient needs further evaluation,” they wrote in his medical records. “He has anemia. And if the oral Candida recurs, it would be useful to check his immune function.” They discharged him on Friday, December 11, 1981.

Had they read the New England Journal of Medicine on Thursday, December 10, they would have found nineteen Noahs in its pages.

+++

Reports were coming in from Los Angeles and New York City of gay men dying from bizarre infections usually seen in transplant patients and rarely in the elderly. Like Noah, their immune systems had been an- nihilated and they were plagued with a dozen different bugs—ubiquitous microbes that rarely caused sickness in young men.

The week that Noah walked out of Wilhelmina hospital, the New Eng- land Journal of Medicine dedicated its entire “original research” section to articles on this strange plague. In one report, scientists from Los Angeles described four gay men who were brewing a fungus, Pneumocystis carinii, inside their lungs, and Candida inside their mouths and rectums. Doctors in New York City puzzled over fifteen men with worn-out immune systems and persistent herpes sores around their anus.

By the time the New England Journal of Medicine article was printed, only seven of the nineteen men in its pages were still alive.

+++

...Four days after Noah walked out of the Wilhelmina hospital, a young man walked into the emergency room at the Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis, or Our Lady Hospital, a ten-minute bike ride away in east Amsterdam.

Dr. Peter Reiss was on call that Tuesday night, his long white coat flapping around his knees as he hurried from bed to bed. Peter and Joep had met in medical school, where they realized they were born a day apart. Joep was one day older than Peter, and he liked to remind his friend of this fact.

Peter picked up the new patient’s chart and stroked his trim brown beard as he read the intake sheet. His bright blue eyes scanned the notes just as he had read the New England Journal of Medicine the previous Thursday.

He walked over to the cubicle and pushed aside the curtain. There was Daniel, a skinny nineteen-year-old with mousey blonde hair, sitting at the edge of the examination table. His skin was pale with bluish half- moons setting beneath his eyes. He was drenched in sweat and hacking a dry cough.

Daniel looked barely pubescent, Peter thought, and he checked the chart for his date of birth. There it was, February 1962. Daniel watched as his young doctor slipped blue gloves over his steady hands. Peter had a broad, reassuring smile and a calm manner.

“Tell me, how long have you been feeling sick?” he asked gently. Daniel had been ill since November. First, a prickly red rash dotted his chest and arms, then itchy red scabs appeared on his bottom. The diarrhea started soon after and he was running to the toilet every few hours. He had a fever that kept creeping higher.

Peter asked if he could palpate his neck and Daniel nodded. Pressing his fingers under the angles of his jaw, the pads of Peter’s fingers found shotty lymph nodes as large as jelly beans. Peering inside Daniel’s mouth, he saw a white blanket of Candida coating his tongue and tonsils. When he stepped back, Daniel coughed and caught his breath and Peter realized that the air had escaped his own lungs, too.

A teenaged boy with enlarged glands, oral thrush, and perianal herpes sounded a lot like the journal articles he had read on Thursday. The case reports flashed through his head: young gay men, history of drug use, American cities.

“Are you sexually active?” Peter asked softly. Daniel looked away. “Yes,” he whispered. “I had sex with a man for the first time ten weeks ago. He was much older than me, forty-two years old, I think. I heard he’s very sick.”

+++

In the summer of 1981...Amsterdam was a safe haven. Lovers from the provinces could walk down the street and do the unthinkable: hold hands, hug, plant playful kisses on their boyfriend’s faces. Here, there was safety in numbers— freedom in a place where gay men were met with smiles instead of slurs. Those who took vacations in the United States reported back that Amsterdam was a lot like San Francisco with its kink bars and bathhouses, places where gay men could hang out and enjoy anonymous sex.

In both cities, the new illness was preying on love and freedom. If colonialism had sparked the spread of HIV from chimpanzees to humans, homophobia was the fuel that helped the epidemic spread from one person to another. The virus was exploiting the need for comfort and community as it swept through bedrooms and bathhouses in the Castro and on Reguliersdwarsstraat.

More than twenty bathhouses dotted San Francisco, including the Fairoaks Hotel, a converted apartment building on the corner of Oak and Stiner. Yoga classes ran alongside therapy sessions and group sex. Wooden-framed signs at the front desk advertised poppers and t-shirts at five dollars apiece.

Disease detectives from the CDC descended on these refuges to col- lect samples and stories, a nameless disease with an unknown mode of transmission giving them license to inject themselves into the private lives of strangers. They offered no answers, only long lists of questions: How many men did you have sex with? What kind of sex was it? Can you write down all your lovers’ names?

The men offered up memories and saliva samples, fearful of what the government doctors would find inside their specimens. The disease detectives were trying to work the investigation like any other outbreak, following the same steps in their usual logical manner. Except this time, the world was watching and waiting for answers.

A handful of diseases have been eliminated from a few pockets of the globe, their numbers dwindling to levels that give humans a sense of dominance over the microbial world. But only one infectious disease has been eradicated: smallpox.

The mastermind behind the global erasure of that virus was Dr. Bill Foege, a looming figure who worked tirelessly to eradicate smallpox in the 1970s. In 1977, he was appointed director of the CDC by President Jimmy Carter.

But a few years into his tenure, Bill’s scientific acumen was up against political fatuity. Carter lost the election to Ronald Reagan, who was sup- ported by a political-action group called the Moral Majority. “AIDS is the wrath of God upon homosexuals,” said its leader, Reverend Jerry Falwell. Pat Buchanan, Reagan’s communication director, said the illness was “nature’s revenge on gay men.”

Reagan said nothing. He uttered the word “AIDS” publicly for the first time in May of 1987 as he neared the end of his presidency. By that time, fifty thousand people were infected around the world and more than twenty thousand Americans had died.

To make matters worse, the Reagan administration demanded cuts in public health spending. Bill had to tighten his purse strings just as the biggest epidemic to hit humanity was taking off.

Even within the CDC, some leaders were doling out politically motivated advice. “Look pretty and do as little as possible,” said Dr. John Bennett, assistant director of the division of the Center for Infectious Diseases. He was speaking to Dr. Don Francis, a young and outspoken epidemiologist who had returned from investigating the world’s first outbreak of Ebola in Zaire.

Bill possessed a stronger will. Armed with political savvy and epide- miologic expertise, he instructed Dr. James Curran to assemble a team. James was head of the research branch of the CDC’s Venereal Disease Control Division. By assigning him a new role, Bill was working the sys- tem to give James enough latitude to conduct what would be the most important investigation of their lives.

James gathered thirty Epidemic Intelligence Service officers and CDC staff to form a task force. Joined by Dr. Wayne Shandera, the Epidemic Intelligence Service officer assigned to Los Angeles County, the task force for Kaposi’s sarcoma and Opportunistic Infections got to work.

The first item on the to do list in any outbreak investigation—even one as devastating as AIDS—is to come up with a case definition, a short list of criteria that will help other doctors look for cases. The disease detec- tives huddled around a table in their Atlanta headquarters and listed the major scourges of the new syndrome.

A case was defined as a person who had Kaposi’s sarcoma or a proven opportunistic infection such as Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. They had to be aged younger than sixty, and they couldn’t have any underlying illness such as cancer or be on any medications that would suppress their immune system.

They shared the case definition with doctors around the country and by the end of 1981, as Noah and Daniel were walking into hospitals in Amsterdam, the CDC had a list of one hundred and fifty-eight American men and one woman who fit the description. Half of them had Kaposi’s sarcoma, 40 percent had Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, and one in ten had both. Looking back, the earliest case they could find was a man who fell sick in 1978.

They looked for connections between the cases and found them- selves writing names on a blackboard and drawing white lines between the people who had sex with one another. A spider’s web of a vast sexual network emerged. Thirteen of the nineteen men who were sick in southern California had had sex with the same man.

Task force Drs. David Auerbach and William Darrow cast their net wider, looking at ninety gay men across a dozen cities who fit the case defi- nition. Forty of those men had sex with the same man, who was also sick. Still, some were vehemently opposed to the idea that the syndrome was sexually transmitted. If it was spread through sex, why hadn’t this happened before? But then came the summer of 1982 and reports of babies and hemophiliacs with Pneumocystis carinii. The common link was blood transfusions. This added a new mode of transmission. Like hepatitis B, the new illness was spread through sex and blood.

The CDC announced four groups of people were most vulnerable to the new illness, hemophiliacs, homosexuals, heroin users, and Hai- tians, and the disease earned a new name: 4H. With that public health announcement came public outrage and vitriol against those groups, especially gay men and Haitians. Houses were burned, children expelled from school, families forced to move towns because they were sick. Poli- ticians sat complicit in their silence.

It was unparalleled, this confluence of public health, politics, clinical medicine, and public anxiety. The unknown disease was spreading faster than imagined. Humanity had never seen anything like it.