Setting the historical record straight for the critics of The New York Times project on slavery in America

Setting the historical record straight for the critics of The New York Times project on slavery in America

Screen Shot of the New York Times homepage for its series, “1619.” New York Times

Kelley Fanto Deetz, University of Virginia

Four hundred years after the event, the New York Times has published a special project focusing on the first Africans arriving in 1619 at Point Comfort, Virginia, and the legacy of slavery in the U.S.

“No aspect of the country that would be formed here has been untouched by the years of slavery that followed,” the introduction said.

While there has been much praise for the project’s recasting of American history, it has been given a chilly reception by others. These critics, including former top GOP legislator Newt Gingrich, attempt to dismiss the significance of the “20 and odd” Africans who arrived in 1619 and the 12.5 million other African people who were sold into the transatlantic slave trade.

“The whole project is a lie,” Gingrich said.

Statements such as one in an article by Joshua Lawson – “By A.D. 1619, slavery had existed for more than 5,000 years, dating back at least to Mesopotamia” – are akin to the recurring social media mantra over recent years that America shouldn’t be blamed, it didn’t invent slavery, and that it’s been around forever.

Screenshot of John Birch Society tweet from Nov. 3, 2016. Twitter

Similarly, social media comments often expresses ideas like: “Who captured them and sold them into slavery in the first place? It was their own people, black people.”

These arguments may sound reasonable because they have a sliver of truth. But as a historian of the African diaspora, I know these characterizations oversimplify the complex history of the slave trade and discourage important conversations about, and an understanding of, American history.

Selling the enemy

First, Africa was not, and is not, a country. Long before the Portuguese made their way to Angola in 1483, to start what became the transatlantic slave trade, African kingdoms, queendoms and empires had long occupied and ruled different parts of the continent, which is close to 12 million square miles.

These centuries-old civilizations were ethnically, linguistically and religiously diverse. Wars were common, as in every other continent, and the people sold to European traders beginning in the 1490s were mostly prisoners of war, not allies.

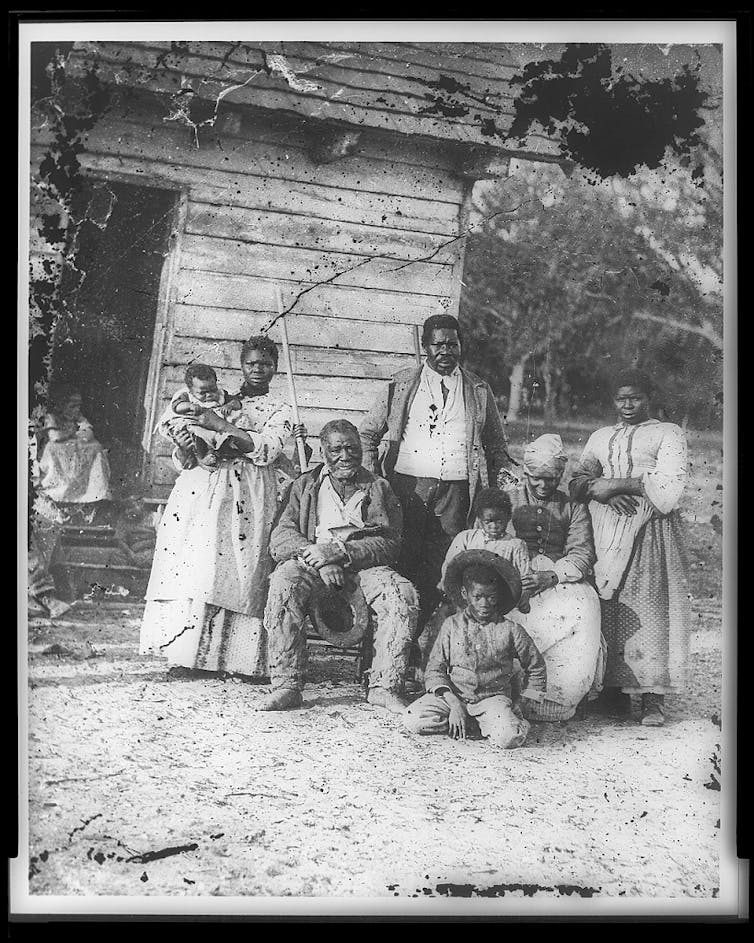

Five generations of slaves on Smith’s Plantation, Beaufort, S.C., in 1862. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Timothy H. O'Sullivan photo

It is true that slavery has been around for thousands of years. But the chorus of social media commentary tries to remove any blame from the country’s forefathers for the American version of the institution and its devastating consequences.

They are correct in their statement that slavery has been around for millennia, and that America did not invent it. But it lacks context and substance that is critical to understanding our nation’s history.

Race-based slavery

Moreover, African traders were not aware of the distinct form of slavery that was to develop in the colonies – one that wed skin color to class in ways never seen before, as it became a distinct product of the trade. That form was drastically different from the African “Old World” models.

Old World slavery was characterized by a more fluid status. The enslaved could own property and legally marry, and their children were not automatically enslaved. Slaves were often criminals, or victims of religious wars. More specifically, slavery in Africa was not a life term, nor was it inherited. The Old World models were more like an indenture, where there was a term of labor to be paid, and then freedom would be granted.

This was nothing like the race-based chattel slavery that grew with the transatlantic trade, which guaranteed a lifetime term and the further enslavement of one’s children.

Almost the entire 12.5 million captured Africans were brought to the Americas as enslaved, not indentured people. Although there are a few exceptions, those few are not representative. European criminals and poor people often held indentured status, and most migrated to the Americas by choice. Those first “20 and odd” Africans were captives, and did not choose their destiny. These are some of the striking differences between European and African laborers.

The legacy of race-based chattel slavery produced distinct trauma over many generations. Its history and legacy of sustained inequality is exceptional.

Race was invented by European colonists to provide an excuse for the systematic oppression of African-descendant people. Race was used to categorize different groups of people based on skin color, and to stratify the different groups into distinct class structures.

The millions of enslaved men, women and children were sold into a land where their skin color became a brand that kept them, and all of their children, enslaved for generations.

“New World” slavery reflected nothing of Old World slavery, and everything of the racial caste system that took hold in the colonies, all in the effort to build both capitalism and colony.

Taking blame from the buyer of slaves, and placing it on the seller, distorts history. Similarly, the history and legacy of Old World slavery and race-based chattel slavery are not parallel.

The United States of America was built on grand ideas of freedom, equality and justice for all. It was also built mostly from the unpaid labor of enslaved African and African American people.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter. ]

Kelley Fanto Deetz, Lecturer in American Studies, University of Virginia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.