A New History of Islamic Empires Defined Through Illustrious Cities

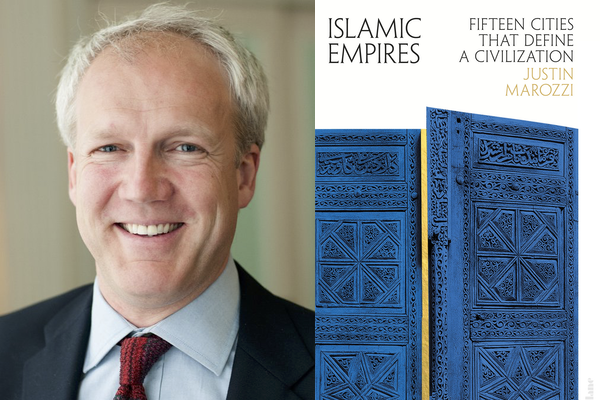

Justin Marozzi is a travel writer and historian. He is the author The Man Who Invented History: Travels with Herodotus, Tamerlane: Sword of Islam, Conqueror of the World, Baghdad: City of Peace, City of Blood, and other books. His latest book, scheduled for release on August 29, is Islamic Empires: Fifteen Cities that Define a Civilization, From Mecca to Dubai. Visit his website. Find him on Twitter @justinmarozzi.

What books are you reading now?

I’m reading Frank Dikötter’s How to be a Dictator: The Cult of Personality in the Twentieth Century, pretty timely, Elie Wiesel’s The Night Trilogy, Peter Pomerantsev’s This is Not Propaganda: Adventures in the War Against Reality and, for light relief, Patrick O’Brian’s Blue at the Mizzen. For years I’ve been resisting the last couple of books in his Aubrey-Maturin series, for fear of finishing this epic roman-fleuve, but I think it’s time to bite the bullet. And as a fellow O’Brian-obsessive consoled me the other day, you can always read them again.

What is your favorite history book?

There is only one contender. Herodotus’ Histories. It’s a one-volume masterpiece, still in print 2,500 years after he wrote it. If you were stranded on a desert island and were only allowed one book for the rest of your life, this is it.

Why did you choose history as your career?

I’m not sure I ever chose it. I’ve always had an interest in travel and history and the two work so well together. I strongly believe that wherever possible, a historian should “walk the ground”, get out of the armchair or lecture room and visit the places he or she is writing about. This is what I have tried to do in my latest book, a history of the Islamic world told through 15 cities across 15 centuries. It’s taken many years living and working in these places to even begin to understand them.

What qualities do you need to be a historian?

Imagination, discipline, patience, an enquiring mind and a sense of wonder all help. As does the ability to write! A willingness to do your own thing, whatever other people around you are doing. And an acceptance that if you choose the independent route, history is unlikely to pay the bills.

Who was your favorite history teacher?

I was lucky enough to have several good ones at school and university. At Cambridge, I was taught by some wonderful historians like Neil McKendrick, Vic Gatrell, David Abulafia and John Adamson. Latterly I became great friends with Paul Cartledge, doyen of Cambridge classicists, while researching my book The Way of Herodotus.

What is your most memorable or rewarding teaching experience?

I don’t teach history but from time to time I tutor aspiring writers on residential courses in the UK. It’s immensely rewarding – mentoring and encouraging and helping them get closer to what they want to achieve.

What are your hopes for history as a discipline?

In the words of the great twentieth-century Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis: “I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I am free.” History will never go out of fashion. Look at how history is being written today. It’s come such a long way from its single-minded obsession with kings and queens, statesmen, generals, battles and wars, laws and constitutions. These days it demonstrates its interest in the ordinary lives of ordinary people, as well as those of our rulers. It’s the most inclusive subject there is. Historians look at sex, sport, culture, domestic lives, economies, revolutions, migrants and the marginalised, as well as the more traditional political and constitutional matters. History constantly refreshes and reinvents itself and that is its abiding power. It has a built-in resistance to obsolescence.

Do you own any rare history or collectible books? Do you collect artifacts related to history?

I have a few old editions of favourite books by favourite writers. Soldiers and explorers like T.E. Lawrence, Doughty, Barth, a Hemingway or two. I have a few mementoes from countries I have lived and worked in and written about. A broken padlock from the notorious Abu Selim prison in Tripoli, which I visited just after its liberation during the 2011 revolution; pieces of carved wood from one of Saddam Hussein’s Baghdad palaces which I use as bookends. A stone from the huge mountain-cairn of stones which legend says were left by Tamerlane’s soldiers en route to war with China in the early fifteenth century. And no end of old Persian rugs!

What have you found most rewarding and most frustrating about your career?

Working alone – and working alone! Writing is an inherently lonely business and if you’re an independent historian, not attached to a university, you have all the freedom – no boss, no publishing requirements, etc. – and none of the support that comes with a large institution. On balance I’ll always err on the side of complete, untrammeled freedom.

What are you doing next?

My new book is Islamic Empires: Fifteen Cities That Define a Civilization, published this summer. It uses fifteen of the most glorious cities within the Islamic world to tell its history, starting from Mecca in the seventh century and ending in Doha in the twenty-first. Along the way we look at Damascus under the Umayyads, Baghdad in its ninth-century heyday under the Abbasids, the First Crusade in Jerusalem in 1099, Marinid Fez, Tamerlane’s Samarkand, Ottoman Sultan Mehmed’s capture of Christian Constantinople in 1453, Babur’s Kabul, Isfahan under Shah Abbas, the extraordinary rise of Beirut in the nineteenth century and the creation of Dubai by the Al Maktoum family in the twentieth. One of the most important lessons these cities show us is the importance of tolerance and moderation. Each of these cities was astonishingly cosmopolitan – Jews, Christians and Muslims coexisting more or less happily – in its heyday. Today, places like Baghdad, Damascus and Tripoli have been hollowed out, their rich, mixed populations hollowed out by external interventions and internal strife. That’s something to reflect on. On a more positive note, much of the world is still flocking to Dubai in a modern-day version of the waves of immigration to Baghdad more than a thousand years ago. Cities are like living organisms. They need to be nurtured.