The hidden story of two African American women looking out from the pages of a 19th-century book

The hidden story of two African American women looking out from the pages of a 19th-century book

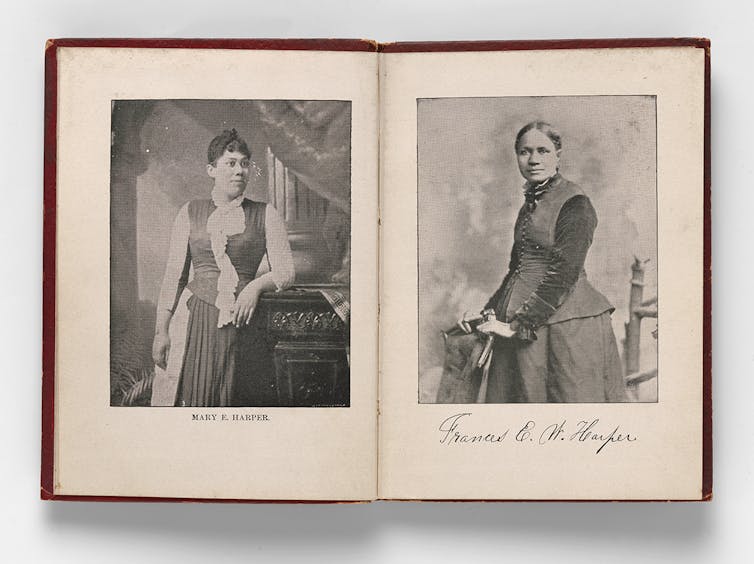

Mary E. Harper (left) and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (right), whose two photos in ‘Atlanta Offering’ are unusual. Unidentified Artist, 1895, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, & Rare Book Library, Emory University, Author provided

Kate Clarke Lemay, Smithsonian Institution and Martha S. Jones, Johns Hopkins University

We are two historians whose work focuses on American art and on how African Americans have shaped the story of American democracy.

Our two subject areas converged recently when one of us had a question, and the other helped her research the answer.

Kate was in the midst of organizing the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition, “Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence,” commemorating the more than 80-year movement for women to obtain the right to vote. This exhibition is part of the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative, Because of Her Story.

While doing her research, Kate encountered a character in history whose story she didn’t know, but who she anticipated would be important to the history the museum wanted to tell.

Who was Mary E. Harper? That’s the question Kate set out to answer.

Kate’s story

In curating the exhibit on the history of women’s voting, it became clear to me that the task at hand was not only to celebrate voting, its history and the ratification of the 19th Amendment, but to expand the ways in which women are written into American history as major players, not as footnotes.

But how could we show that history?

Objects. That’s what we use in museums to shed light on people’s lives.

Photographic portraits, and genre paintings depicting scenes of everyday life, as well as items from history like posters, drawings and maps, help us learn about and understand the stories of the countless women who lobbied to include women’s voting rights in their state constitutions.

These women, along with those who organized and led the lobbying of states to ratify the 19th Amendment, which established women’s right to vote, have been left largely outside of American historical accounts.

So I worked to make sure “Votes for Women” included portraits of women whose biographies are less well known.

And in my search for objects that would represent their lives, I came across a few surprises.

I was looking for portraits that were made from life – so a product of a personal meeting – and from the specific period of the suffragist’s life.

I very much wanted to feature the African American lecturer, novelist and poet Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825-1911), because of her activism in the American Equal Rights Association, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and other women’s groups affiliated with churches.

One quote of hers provides a glimpse of her ideals: “We are all bound up in one great bundle of humanity, and society cannot trample on the weakest and feeblest of its members without receiving the curse of its own soul.”

Newspaper clippings from 1871 praising Frances Ellen Watkins Harper’s public speaking. Click to enlarge. Newspapers.com

I found the perfect object to represent her in the collections of Emory University. It was a first edition of “Atlanta Offering,” a book of Harper’s poetry published in 1895 in Philadelphia. An Emory archivist forwarded me a digital version of it, demonstrating its pristine condition.

Books like these often have a frontispiece, a picture or portrait of the author or the book’s subject in the opening pages, usually facing the title page of the book.

This book featured a frontispiece of Harper wearing a suit – a floor-length skirt and a sleeveless bodice with covered buttons down its front. Underneath the bodice, her velvet shirtwaist ends in cuffs with ruffles around her wrists, and at her neck is tied a ribbon. A bit of white ruffle at her neck suggests a shirtwaist worn under the velvet.

These details in costume signify a refined woman, while Harper’s gaze looking directly at the camera suggests great confidence.

When the book arrived and I opened it pages to display Harper, I saw something unusual. There was not just one portrait at the front of the volume – there were two.

I was surprised to see this second frontispiece because I had been looking at a digital version of the book and hadn’t been able to see both pages at once. The second portrait was a woman named Mary E. Harper. Who was this second woman?

I could see by examining the details of her costume that Mary was as dignified as Frances. But why would her portrait be featured so prominently in this work of poetry, and what meaning can we take away from this publication choice?

To answer my questions, I consulted with Martha S. Jones, an expert on Frances Ellen Watkins Harper.

Martha’s story

I was as intrigued as curator Kate Clarke Lemay when I saw that the Frances Ellen Watkins Harper volume, “Atlanta Offering,” included not one but two portraits.

My intrigue ran deep because I am familiar with this particular portrait of Frances; it circulates widely and even illustrates my first book, “All Bound Up Together: The Woman Question in African American Public Culture,” the title of which borrows from one of her speeches.

Increasingly, researchers like me are using materials that have been digitized – including books like “Atlanta Offering.” Clicking through images on a laptop risks missing interesting and important details. This was certainly true for me and helps explain how I had managed to overlook Mary E. Harper.

Overlooking Mary E. Harper’s portrait is an apt metaphor for how she has been overlooked in historical studies.

What I found when I went searching in archival material was that Mary is Frances’ daughter. She is largely absent from an extensive body of scholarship on her mother, who was a talented public speaker and prolific writer. Still, there is one thing that scholars agree on: Frances was devoted to Mary.

Mary was just an infant when her father, Fenton Harper, died, leaving their Ohio household destitute. The widowed Frances left Fenton’s three children from a prior marriage in the custody of relatives, but she kept Mary with her and headed back east to rebuilt her life and her career.

We know little about Mary’s early education. It is likely she attended schools in Baltimore and Philadelphia. By the 1880s, in her teens, Mary followed in her mother’s path and enrolled in Philadelphia’s National School of Elocution and Oratory.

Graduating in 1884, Mary was poised to begin a career that turned on her capacity to deliver eloquent, polished and entertaining readings. Her first performances were in Philadelphia’s private parlors and a home for the elderly. But Mary was ambitious, and she set out to build a reputation that would win her audiences across the country.

Mary’s career did not merely mirror that of her mother, Frances, who had built her style and reputation on the demanding and unorthodox terrain of the anti-slavery lecture circuit. Mary’s presentations featured poetry and literature, and to a lesser degree temperance, not politics. Sometimes she performed with musical troupes.

Throughout, she carefully built a repertoire that maintained her appeal to respectable, middle-class and Christian audiences. By the late 1880s, she had broken through. Newspapers report her traversing the country on tours that took her west to Ohio, Missouri and Wisconsin, north to Massachusetts, and south to Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia.

The precise end of Mary’s life has eluded me. We know that she died in 1908, three years before her mother. The two are buried side by side in a Delaware County, Pennsylvania cemetery.

I’d like to think that in 1895 Frances Ellen Watkins Harper made the extra effort to include Mary’s portrait alongside her own just so that curator Kate Clarke Lemay would find it. Frances would be pleased, I am certain, to know that her small tribute to a beloved and gifted daughter has inspired us to recover some of Mary’s remarkable life.

Kate Clarke Lemay is the author of:

Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence

Princeton University Press provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

Kate Clarke Lemay, Historian, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution and Martha S. Jones, Society of Black Alumni Presidential Professor and Professor of History, Johns Hopkins University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.