Why Televised Hearings Mattered During Watergate But May Not Today

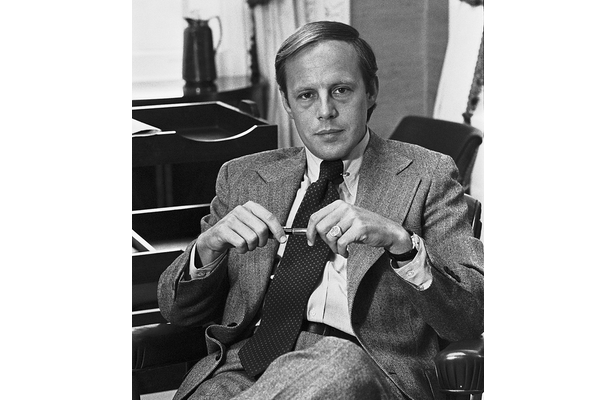

John Dean

I started a continuing legal education program with John Dean in 2011. We have done over one-hundred-and-fifty programs across the nation since then.

Our first program was about obstruction of justice and how Dean, as Nixon’s White House Counsel, navigated the stormy waters when he turned on the president and became history’s most important whistleblower. Unlike the current whistleblower, Dean had been involved in the cover-up, but ultimately decided he had to end the criminal activity in the White House, with no assurance of anonymity and with the almost certain expectation that he was blowing himself up in the process.

Dean was placed in the witness protection program but became one of the most recognized figures of his time. When he testified before the Senate Select Committee for the entire third week of June 1973, all three networks carried his testimony, gavel-to-gavel. John Lennon and Yoko Ono showed up to watch Dean. Almost all of America tuned-in and some reports estimated there were 80 million viewers. In our history we have had only a handful of such mega-TV events: the Kennedy assassination weekend, the Apollo landing on the moon, and the attacks on 9-11 come to mind.

Yet is wasn’t until a year after Dean testified that Nixon resigned. The process of Nixon’s take-down was slow but steady, a phenomenon that many historians refer to as a “drip, drip, drip.” Nixon’s credibility kept absorbing one body shock after another: first the Senate hearings, then the discovery of the taping system, the firing of the Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox, the discovery of a gap in the tapes, the indictment of top Administration officials, and finally, the Supreme Court ruling in late July 1974 that tapes had to be turned over.

One tape dealt the knockout blow. It became known as the “smoking gun tape,” because it showed the president a week after the break-in, on June 23, 1972, ordering his chief of staff to call in the CIA and instruct them to tell the FBI to end its investigation into Watergate, as it might uncover CIA operations. This both killed Nixon’s lie that he knew nothing of the cover-up and displayed the kind of abuse of presidential power that the founders worried about when they agreed to insert an impeachment outlet in Article II of the Constitution. The president was seeking to use his office for his own personal political protection.

In the current situation, the “smoking gun” has already been produced in the form of the partial transcript of President Trump’s July conversation with President Zelensky. Despite what Trump says, it shows him bargaining for political dirt on his adversary through the misuse of his presidential powers.

The whistleblower today has been backed up by others who had direct knowledge, making his or her account now superfluous. John Dean had no such back-up from others; he had to wait a year for his testimony to be fully corroborated by the tapes themselves.

Because the nation also had to wait almost a year to determine who to believe, there was time for Dean’s testimony in June 1973 to take hold and sink in. Nixon had won reelection by a landslide in November 1972 and his approval rating was nearing 70% in January 1973, when he kept his promise to end America’s involvement in the Vietnam War. But with the burglars’ trial before Judge John Sirica in January 1973 and the unanimous Senate vote to investigate campaign activities from the 1972 election on February 7, 1973, things began to spiral.

In April 1973 when Nixon fired his top advisors and attorney general, Dean was also let go. Nixon’s approval rating fell to 48%. Then John Dean testified in June and Nixon’s popularity fell as low as 31% by August. Nonetheless, despite the widespread opinion that Nixon was somehow culpable in the break-in, only 26% thought he should be impeached and forced to resign; 61% did not. The calls for impeachment and removal didn’t reach a clear majority until the “smoking gun tape” was produced in late July 1974. Then the number rose to 57%. By that time Nixon’s approval rating had sunk to 24%.

What this tells us is that the televised hearings started the path downward in June 1973, though it took a year of continuing scandal to wipe out Nixon’s support. Importantly, Dean’s testimony that he thought he might have been taped in one instance led Senate investigators to Alexander Butterfield and the revelation that the taping system existed. It was the fight for the tapes that confounded Nixon and his defenders and ultimately led to his resignation.

The current impeachment inquiry will be Watergate in reverse. The whistleblower has already surfaced the “smoking gun” transcript. Others have already verified the whistleblower’s allegations. The televised hearings, while they will add public understanding of what happened, are coming after years of scandal and revelations about Mr. Trump. Between the expected impeachment by the House at year-end and the trial in the Senate early next winter, there will be little time to let the pot boil as it did in Watergate. And it is doubtful, given the depth of the partisan divide and media bias and agendas, that the polls on impeachment and removal will shift a great deal with the televised hearings.

The public knows what Trump did. They generally know it was wrong. Trump supporters simply don’t care. Even with the attempt to have foreign interference in our elections all but confirmed, the President’s followers are unmoved.

Perhaps I will be proved wrong, but I think the televised hearings will not significantly move the needle of public opinion as happened during Watergate. The House will impeach. The Senate will not convict. And those Republicans who stand behind the President will have to answer to voters when their time comes. So will President Trump.