Reform or Revolution: England’s Lessons of 1688 for Today and Tonight's Democratic Debate

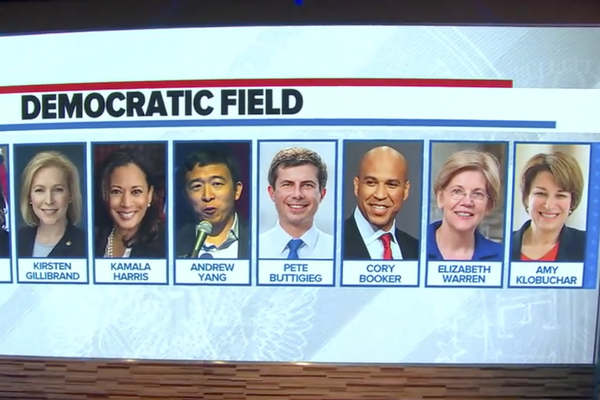

Tonight’s debate will once again expose a tension between moderates and leftists in the Democratic Party. At the core of this tension is a debate over how to bring about political change: through reform, or through revolution?

This debate goes back centuries, especially when discussing England and France. In England, the Glorious Revolution of 1688 achieved a moderate reform of the English political system. Conversely, the French Revolution that began in 1789 seemed to usher in a new era of hard-edged revolutionary politics, with worldwide reverberations. In both cases, people struggled for genuine change in the face of undoubted injustice. Yet England managed to implement key reforms while still maintaining historic institutions. The French, on the other hand, struggled for equilibrium, enduring a succession of failed governments and horrific violence. The lesson: That institutions can prove surprisingly flexible, something that can bode well for reform impulses.

The English Glorious Revolution of 1688 occurred when the English overthrew the absolutist, tyrannical monarchy of James II (r. 1685-88), the last male Stuart ruler. Unwilling to subject themselves to James’ flagrant violations of core English liberties, parliamentary liberals invited James’ daughter Mary to rule England with her husband, William, from the Dutch House of Orange. Living in the Netherlands, William and Mary crossed the Channel, meeting surprisingly little resistance from James. Because it avoided violence and extremism, the English called this bloodless takeover of the throne “glorious.”

With William and Mary established as co-rulers, Parliament presented the monarchs with a Bill of Rights, which they promptly signed. Going forward, the English Bill of Rights provided a prototype for what would later become a hallmark of Enlightenment-era liberal idealism — a written constitution guaranteeing liberties. Some of the classic freedoms instituted in the Bill of Rights included things like the freedom to debate and the right of subjects to petition the king. Overnight, the English Bill of Rights turned England from an absolutist state into a constitutional monarchy, one of history’s most successful parliamentary systems.

The Glorious Revolution deeply influenced subsequent politics, and not just in England. In the aftermath, the political philosopher John Locke re-articulated the Bill of Rights’ ideas about fundamental liberties existing beyond the reach of the state. American documents, like the Federalist Papers, or the Declaration of Independence, often echoed John Locke’s language about inalienable rights and the role of the state in protecting them. The Eighth Amendment’s ban on “cruel and unusual punishment” quotes the English Bill of Rights, virtually verbatim.

Still today, the American structure of government reflects ideas from the Glorious Revolution. However imperfectly realized, these ideals continue to shape American values. According to law, Congress has the power of the purse. America does not use standing armies to police the citizenry. No ruler is above the law. People have a right to speak their minds. Such principles are at the heart of current American debates, ranging from the impeachment of President Trump to the Black Lives Matter movement.

While the English enumerated all these core political ideals, and avoided social and cultural tumult, others were not so lucky. America achieved its freedom in relatively moderate fashion, but only after a military war of independence. In contrast, the French Revolution of 1789 provided another model for change that was far more violent.

During the French Revolution, the push for change pitted reformers against revolutionaries. Sitting on the proverbial “left” of the assembly hall, the Parisian faction usually pushed for radical change, at a faster pace. Their goals were often laudable, including liberty, equality, and fraternity, the Revolution’s slogan. But as events veered out of control, the French revolutionaries seemed to grow increasingly impatient. Some of their most famous efforts included taking France off the Gregorian calendar and starting a new religion, the Cult of the Supreme Being. They moved to remove statues, and even entire buildings, that represented the values and ideals of the old days.

In contrast to the revolutionary Parisian faction, moderate French reformers pushed for more measured change. Initially, they wanted to keep the monarchy and a viable Roman Catholic Church, which had been central to French history and identity. By 1792, however, the French had abolished the monarchy and disestablished the Church, breaking with the Vatican. A few years earlier, few would have even imagined such tumultuous change possible, let alone advocated it. Once events began to escalate, however, they proved hard to stop, pushed by a potent combination of ideological extremism and social unrest. A climate of emergency and scarcity gripped the nation. Seemingly impossible circumstances sometimes made it seem like France had lost control of itself.

Both the ranks of the English reformers and the French revolutionaries included plenty of good people who sincerely wanted the best for their respective countries. They just often disagreed on how to get there. In France, the revolutionaries sought to change France in ways that seemed practically fundamental. But they still needed to preserve order in the streets and bread in the markets – the basic functions of any decent government. Meanwhile, an irresistible need for stability helped popularize the military authoritarianism of Napoleon, who took power in late 1799.

In contrast to France, the English experience in 1688 affirms that a society can achieve reforms without descending into chaos and violence. It reminds us that we can strive together for improvement without attacking the country’s history and people. Reform does not require holding earlier versions of ourselves in contempt, actually, quite the opposite.

As we go forward into the holidays, and then a contentious election, the English example in 1688 continues to provide an important lesson. We can cherish our history and institutions, while still being clear-eyed about necessary changes. Today, England is one of America’s oldest, and closest, allies. Hopefully, this English tradition of reform offers vision that all Americans can share—Democrats, Republicans, and independents alike.