Confederate Monuments in National Perspective

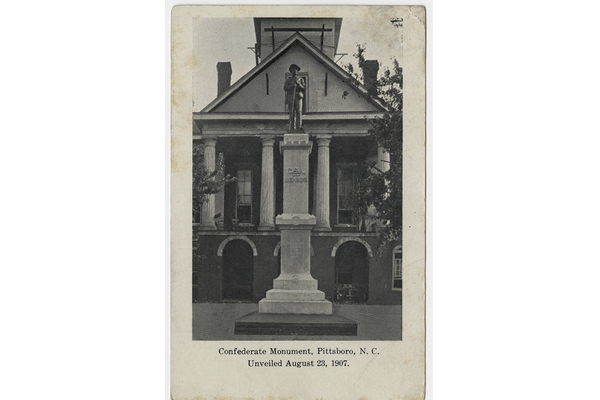

Confederate Monument in Pittsboro, North Carolina

The recent removal of a Confederate memorial in Chatham County, North Carolina, indicates that communities continue to discuss the future of monuments to white supremacism despite the efforts of some state legislatures to suppress municipal governance. The displaced Pittsboro soldier statue, produced by the W. H. Mullins Company of Salem, Ohio, serves as a reminder that Confederate monuments took shape in commercial and cultural contexts that extended beyond the former slaveholding states. Northern commemoration introduced the martial metaphors of social regulation that white southerners adapted to local settings, though some Union monuments instead demonstrated the more inspiring potential of war memorials.

My new book, Civil War Monuments and the Militarization of America, presents a nation-wide examination of this important cultural form. Extremely rare before the Civil War, public monuments to common soldiers radiated primarily from the Northeast in the 1860s. Some early memorials marked places of interment, but more were community cenotaphs for local soldiers whose remains were collected in distant cemeteries. A new surge of production accompanied the invigoration of the veteran movement in the 1880s. In the North as well as the South, monuments proliferated dramatically until World War I and more slowly over the next quarter-century. The tributes increasingly honored all soldiers from a community—like the 1907 statue in Pittsboro--rather than singling out the dead. The North installed more monuments than the South, and considerably more of the memorials that most fully explored the possibilities of the practice.

Civil War monuments were the chief instrument by which the soldier replaced the farmer as the prototypical American citizen. The substitution of a military exemplar signaled a forcible insistence on the labor and racial orders hardening in this age of inequality. The factory worker was the true successor to the farmer as the characteristic laborer of the industrial era, but the soldier personified the conformity and vigor that monument sponsors expected from ordinary citizens. “The glory of the private soldier of the South was that, an intelligent unit, he permitted himself, for duty and love, to be made into the cog of a wheel," declared industrialist Julian S. Carr at the 1917 dedication of a memorial in the manufacturing town of Rocky Mount, North Carolina. The high-profile deployment of troops to break strikes across the North during the late nineteenth century underscored the tension between the paragon of obedience and workers’ challenges to industrial hierarchy.

Celebration of proslavery rebellion in a subsequent society defined by segregation, disfranchisement, racialized incarceration, and lynching certainly distinguished Confederate monuments from their Union counterparts, but exaltation of whiteness was also important to northern memorials. Protests against bronze or stone soldiers based on Irish, Italian, or German models illustrated ethnic prejudices common amid the mass immigration to the North. Some Union memorials incorporated pseudo-Darwinist ideology. The well-publicized model for the allegorical figure on the 1913 memorial in Adams County, Indiana, was Margaret McMasters van Slyke, whom Physical Culture editor Bernarr McFadden had judged Chicago's "most perfectly formed woman" as measured by the features that the eugenicist considered essential to sexual reproduction of the fittest national race.

Theo Alice Ruggles Kitson’s Volunteer, unveiled in Newburyport, Massachusetts, in 1902 was an especially elaborate example of this pattern. The acclaimed statue drew on studies of marching by Edward H. Bradford, professor of orthopedics and later dean at Harvard Medical School. In this conceptualization, experienced soldiers eschewed the straight-leg, heel-to-toe gait of urban pedestrians and instead leveraged gravity in a bent-leg, full-foot stride characteristic of “moccasined and semicivilized nations.” The veteran embodied the supposed power of civilized whites to absorb the strengths of “inferior” races. Like other innovations in the design of soldier monuments, The Volunteer prompted reproductions and imitations across the country. Kitson would go on to produce the most influential common-soldier statue of the Spanish-American War, The Hiker, first installed at the University of Minnesota in 1906. Building on the conjunction of martial training and whiteness, The Hiker explicitly honored full-time regulars of the U. S. Army, rather than the temporary volunteers who dominated Civil War monuments, and depicted the hero in the imperialist project of “hiking,” which, as Sarah Beetham has noted in an excellent dissertation on common-soldier monuments, referred specifically to hunting insurgents in the mountains of the Philippines. This monument, too, was reproduced across the North and South.

Scholarly discussion of northern contexts for Confederate commemoration has centered on the level of resistance or deference to the Lost Cause. Community memorials regarded Union soldiers as, in the oft-quoted words of James Garfield, “everlastingly right,” much as sponsors of Confederate monuments insisted that “we cannot praise and commend the martyr and at the same time condemn the cause for which he gave his life.” But over time, many northern memorials shifted from Union monuments to soldier monuments, indicative of a general military readiness and routinely supplemented to honor combatants in earlier or later wars. Extending this logic, a few northern sponsors eager to reach national audiences dismissed the moral gulf between blue and grey. Yale listed its Union and Confederate dead on the university memorial installed in 1915. Princeton did not even identify the sides on which its former students fought. Although unusual, these tributes illustrated a widespread attempt to depoliticize soldiering. Northern monuments established a foundation for the argument that Confederate military service deserves recognition although rendered in a deplorable cause.

Union monuments contributed significantly to the disturbing ideology of Confederate monuments but also pointed toward higher potential in war memorials. Postwar cenotaphs, committed to preserving the individuality of lost neighbors, pioneered the interchangeability of names and bodies that Thomas Laqueur has called the hallmark of the age of necronominalism. Focused on the tensions between intimate realms and national mobilization, these works created the space for "personal reflection and private reckoning” that Maya Lin later sought in the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Early memorial halls—designed to serve as educational buildings, public libraries, or centers of municipal government—envisioned an engaged, informed citizenry as the basis for military voluntarism in times of crisis, rather than the aggressive ideal of masculinity promoted by later monuments. The list of successes might be extended. Much as the large area of overlap between Union and Confederate monuments provides valuable context for current discussions, so do distinctive features of memorials on either side.

For more by this author, read: