The History of Presidential Misconduct Beyond Watergate and Iran-Contra

In 1974, James Banner was 1 of 14 historians tasked with creating a report on presidential misconduct and how presidents and their families responded to the charges. The resulting report was a chronicle of presidential misconduct from George Washington to Lyndon B. Johnson. It indicated moments of corruption, episode by episode with no connective tissue between administrations.

The historians delivered the report in eight weeks and it was prepared for distribution to the House Judiciary Committee. But then Richard Nixon resigned and the hearings it was designed for never happened. The report was published as a book but it got very little attention. Very few American historians even heard of it. “And thus it lay,” stated Banner.

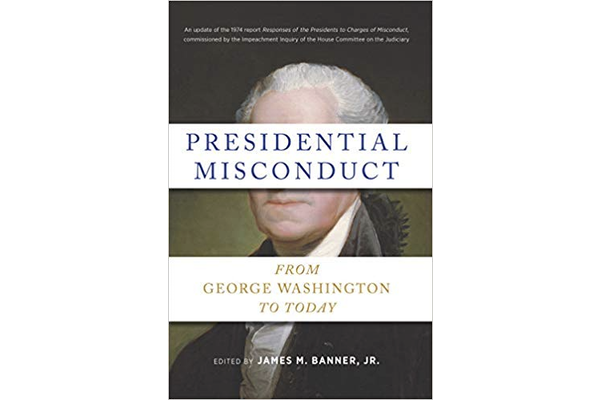

Then, in August 2018 historian Jill Lepore called Banner and asked him about the book. Afterwards, Lepore wrote about the 1974 report in the New Yorker and the press and surrounding political events ignited interest in it. To bring the chronicle of presidential misconduct up to date, Banner identified and recruited seven historians to write new chapters so that a new version of the book would end with Barack Obama. Presidential Misconduct: From George Washington to Today was published by the New Press in July 2019.

At the American Historical Association’s annual meeting in early January, Banner monitored a panel with three of the book’s new authors: Kathryn Olmstead, Kevin M. Kruse, and Jeremi Suri. Examining the presidencies of Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter, and Ronald Reagan, the historians discussed how the recent past shapes the current discussion of presidential misconduct.

Kathryn Olmstead examined presidential misconduct beyond Watergate in the Richard Nixon administration and argued abuse of power and law-breaking were central to Nixon’s presidency.

Dr. Olmstead urged historians to remember just how unusual Nixon was. Popular accounts of Watergate often minimize the crimes and focus on the subsequent cover-up, but Nixon’s crimes were substantial and began before he was elected.

During the 1968 election, President Lyndon B. Johnson announced that if the North Vietnamese made certain concessions, LBJ would halt bombing campaigns and being negotiations with the North Vietnamese. Nixon publicly agreed with LBJ’s stance, but privately he took action to sabotage the plan. Nixon appointed Anna Chennault, a prominent Republican fund-raiser, as a go-between to encourage South Vietnam to not accept the negotiations. When North Vietnam signaled it would make the necessary concessions, many thought the war would end and Hubert Humphrey, the Democratic candidate for president, started to do better in the polls. Then, the South Vietnamese indicated that the concessions would not be sufficient for them to negotiate.

LBJ knew Nixon influenced the potential negotiations because he instructed the FBI to listen to Nixon’s phone calls. LBJ believed Nixon’s actions amounted to treason but he did not have definitive proof to show Nixon knew about the entire operation so LBJ did not reveal the information publicly.

It is likely the Chennault Affair contributed to the paranoia that eventually led to the Watergate break-in. F.B.I. Director J. Edgar Hoover informed Nixon that LBJ knew of Nixon’s role in sabotaging negotiations with North Vietnam and Nixon became obsessed with the idea that the Democrats had information that could hurt him.

Once in office, Nixon’s illegal behavior snowballed. Nixon authorized secret bombings of Cambodia, warrantless wiretaps on news reporters, and created the infamous “Plumbers.” The Committee to Reelect the President raised 20 million dollars--much of it acquired through bribery and extortion--and then used the funds for massive harassment and surveillance of Democrats during the 1972 election.

Thus, illegal behavior was central to Nixon’s conception of the presidency. Nixon himself explained this to David Frost in 1977. Nixon insisted he should have destroyed the tapes and maintained that “when a president does it that means it’s not illegal.”

Princeton historian Kevin Kruse discussed the presidency of Jimmy Carter. While Carter had a pronounced commitment to ethical government, a closer look at Carter’s presidency shows that even those who tried to meet anticorruption standards can be brought low by their efforts.

Even before Watergate, Carter presented himself as a political outsider. After Watergate, Carter capitalized on American concerns about a lack of morals in politics. Carter wanted to seem as trustworthy as possible on the campaign and after he was elected he worked to maintain the public’s trust. Carter famously put his peanut farm into a blind trust and the White House implemented stricter rules regarding conflicts of interest and financial disclosure.

Because of these promises, Carter’s family came under intense scrutiny and the constant hunt for dirt hurt the administration.

Carter asked Burt Lance, the incoming manager of the Office of Budget, to put his stocks in a blind trust. Lance agreed but then the stocks began to plummet to Lance delayed doing it. In response, a Senate committee and Comptroller General opened investigations into Lance. The investigations revealed sloppiness but concluded there was no wrongdoing. Nonetheless, Carter’s administration was consumed by the Lance investigation and Carter stuck by his friend despite his staff’s recommendation to fire Lance. Finally, in the fall of 1977 Carter pressed Lance to resign and in retrospect Carter realized he should have sooner.

Next, a scandal emerged centered on Carter’s peanut warehouse that was put in a blind trust. As the business had fallen on hard times, it was revealed that Bruce Lance had once given a loan to the warehouse. Many were concerned that the funds were diverted to Carter’s campaign. A team of investigators reviewed 80,000 documents and Carter even gave a sworn deposition (this was the first time a president was interviewed under oath in a criminal investigation). The investigation concluded there was no evidence was diverted.

The third scandal of Carter’s administration centered on Billy Carter. Billy ran a gas station and when the business started to struggle, Billy tried to capitalize on his brother’s fame. In September 1978, Billy took a trip to Libya seeking to make a deal with Muammar Gaddafi. While there, Billy made anti-Semitic comments and urinated on the airport tarmac. This all caused a great deal of embarrassment for Jimmy Carter. Worse, it was soon revealed that Billy had received hundreds of thousands of dollars in loans from Libya. The scandal was dubbed Billygate. After a Senate investigation, a bipartisan report concluded Billy had not done anything illegal.

These sloppy practices each invited close investigation but in each case, officials concluded the acts were not criminal. Nonetheless, these scandals overshadowed much of Carter’s presidency and demonstrate that Carter’s action never lived up to his high-minded intensions.

Jeremi Suri, a historian at the University of Texas at Austin, discussed presidential scandal during the Ronald Reagan administration. Suri noted that he was surprised at how little attention historians have paid to presidential misconduct, likely because historians like to stay away from scandal and research more “serious” events. Suri, however, thinks that misconduct was central to policy for Reagan.

Scandal under Reagan is a paradox because Reagan personally was not corrupt—he did not personally get money from misconduct—and was adverse to discussions he thought were unseemly. Nonetheless, because of his personal qualities, Reagan’s policies were built on a pyramid of misconduct or a “cocktail of corruption” centered on the intersection of deregulation, ideological and at times religious zealotry, lavish resources, and personal isolation from the daily uses of those resources.

In other words, the institutional structure of the executive branch created incentives for corrupt behavior. Strikingly, over 100 members of the Reagan administration were prosecuted and 130 billion dollars were diverted from taxpayer uses.

Dr. Suri focused on a few particular scandals and started with the Environmental Protection Agency scandal. Reagan appointed Anne Gorsuch, the mother of Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch, as the administrator of the EPA. Gorsuch directly negotiated contracts with land developers and when she was investigated, Gorsuch refused to turn over documents or testify and was held in contempt of court. Her deputy served two years in prison.

Secretary of the Interior James Watt was forced to resign after he made explicitly racist comments. After resignation, Watt used his connections to work with the Department of Housing and Urban Development and lobby for his friends to get contracts to build affordable housing that wasn’t actually affordable. Watts was convicted on 25 felony accounts.

As Reagan approached his second term, many advisors resigned and became lobbyists, flagrantly going past the legal limitations on lobbying. Those who continued to work in the White House continued the corruption that plagued the administration in its first term.

Attorney General Edward Meese combined petty corruption with the gargantuan. Niece would try to get double reimbursed for expenses. He took out personal loans from people who were bidding for government contracts, would not disclose the loans, and then would lobby for the loaners to get the contracts. Niece was not convicted but resigned.

Assistant Secretary of the Navy Melvin Paisley stole 622 million dollars from the government. The F.B.I. concluded this was a consequence of large-scale appropriations with insufficient oversight.

Suri argued that the Savings and Loans Crisis and the Iran Contra scandal emerged from an administrative culture that was unregulated, permissive in the misuse of resources, and lavish in spending. He concluded that this structural corruption has not gone away.

To conclude the panel, James Banner gave a thoughtful comment that connected the history discussed to the present impeachment of President Donald Trump. Nixon was a pioneer in orchestrating misconduct from the oval office. Reagan pioneered allowing a shadow administration to implement policies that were not approved by Congress. To Banner, it seems that the Trump administration is doing both of these things at the same time.