Universities must open their archives and share their oppressive pasts

Universities must open their archives and share their oppressive pasts

The archives of academic institutions can tell previously untold stories of eugenics. Universities can begin to undo oppressive legacies by opening them to artists and communities. (Pakula Piotr/Shutterstock)

Evadne Kelly, University of Guelph and Carla Rice, University of Guelph

For the first time, a Canadian university — the University of Guelph — is reconciling with its history of teaching eugenics. Few universities in Canada have looked closely at their historical involvement in oppressive research, teaching and practice. Fewer still have made their archives accessible.

Through the first half of the 1900s, the eugenics movement had close ties to post-secondary institutions. For example, leaders at the University of Alberta also engaged in the eugenics movement and at the Alberta Eugenics Board. Two of the three founding colleges of the University of Guelph — the Macdonald Institute and the Ontario Agricultural College — officially taught eugenics between 1914 and 1948.

Once, eugenics spread the deeply damaging idea that it is possible, and even desirable, to improve the human race through selective breeding. It ultimately spawned policies aimed at eradicating those deemed “unfit” through institutional confinement, restrictive marriage, immigration laws and sterilization. Eugenics was considered a science from the early 1900s until the 1930s, when its scientific reputation began to decline and shift.

Exhibiting eugenics

Canadian universities have restricted access to those archives that implicate their institutions in profiting from oppressive ideas and practices. Kathryn Harvey, the school’s head archivist, made the University of Guelph archive available to us.

Using the archives, we developed a co-created, multimedia and multi-sensory exhibition at the Guelph Civic Museum called Into the Light: Eugenics and Education in Southern Ontario, which began in September 2019 and runs until March 2020. It is the first of its kind to bring to light the difficult history of Canadian university involvement in teaching eugenics.

Into the Light is co-created by Mona Stonefish (our project Elder), Peter Park, Dolleen Tisawii’ashii Manning, Evadne Kelly, Seika Boye and Sky Stonefish, with key supports from Carla Rice (ReVision Centre), Dawn Owen (Guelph Civic Museum) and Sue Hutton (Respecting Rights, a project at ARCH Disability Law Centre). It brings together Indigenous and disabled people who carry personal histories of forced confinement and sterilization.

The exhibition embraces disability and decolonizing curatorial practices that disrupt and unsettle. By presenting artistic, sensory and material expressions of memory through different formats, it “speaks the hard truths of colonialism” as Ho-Chunk scholar Amy Lonetree writes. By showing more than 30 years of eugenics course documents (1914-48) from the Macdonald Institute and Ontario Agricultural College, it is thus a rare opportunity to consider how eugenics was taught and practised in Ontario.

Teaching eugenics

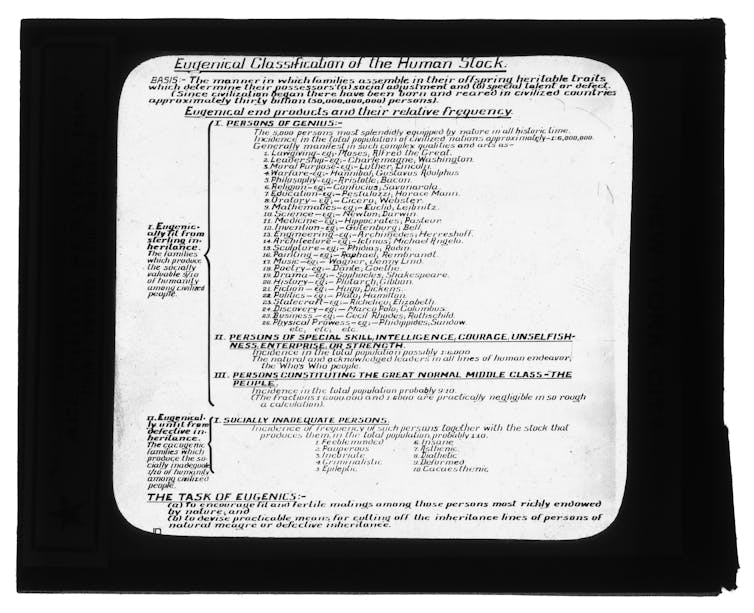

In Into the Light, the eugenics course documents are accompanied by multiple perspectives. Take, for example, one of the course slides, entitled “Eugenical Classification of the Human Stock” that was initially displayed at the Second International Eugenics Congress in 1921.

‘Eugenical Classification of the Human Stock.’ The image shows a chart with a list of those considered eugenically fit followed by a list of the unfit. (Courtesy of Archives and Special Collections, University of Guelph)

The chart shows the connection between eugenics and British colonialism. In it, Cecil Rhodes is classified as a “superior” person of “genius.” In 1921, Rhodes was celebrated for his forceful British colonial and white supremacist agenda. Today, Rhodes is recognized as an early architect of apartheid, a policy that involved the systematic dehumanization of South Africa’s Black population from 1948 to 1994.

Also shown on the chart are the eugenic traits of those whom eugenicists deemed to be “unfit,” including people classified as feeble-minded, poor, criminal and epileptic. In the process of claiming the land and its peoples, Canadian colonial administrators, officers, physicians, educators and scientists framed First Peoples as impaired and “mentally unfit” in order to justify their actions. As decolonizing scholar Karen Stote writes in An Act of Genocide, this was a precursor to unethical sterilization and forced institutionalization.

The effects of colonialism and eugenics are seen in two large stacks of food sacks. The sacks reveal the forced domestic and agricultural labour imposed on those who were placed, sometimes violently, in Ontario residential institutions.

The sacks are accompanied by the smell of rotting potato to evoke the feeling of being denied comfort and nutrition.

The eugenics course suppressed independent thinking and experiential knowledges. But Into The Light centres once-marginalized survivor experiences and encourages viewers to think critically.

As demonstrated in this image, food was often used to perpetuate colonialism. In a section of the exhibit at the Guelph Civic Museum, there is a stack of potato sacks, created by the artists, which shows a stereotypical image of an ‘Indian’ with ‘Eugenics Brand’ written on the sacks. Bright light streams between the sacks. (Evadne Kelly)

The effect of eugenics

The exhibition has had a jarring impact on university students, especially those in psychology, sociology, human development, political science and social work who are aiming for careers in the same professions that once supported eugenics.

One psychology graduate student, for example, spoke about how his relationship towards the University of Guelph transformed after visiting the exhibition. When he learned about the university’s role in teaching eugenics, his pride quickly turned to feelings of discomfort and disorientation. But he became open and eager to change when he realized that the university chose to expose and address its history instead of trying to cover it up.

For survivors and aggrieved groups, the display of archival documents has had an impact also. One survivor of the Mohawk Institute and the Training School for Girls said she felt relieved and validated after decades of being silenced, denied and disbelieved — all of which compounded the crimes she experienced due to eugenics.

Dalhousie University and Ryerson University are two schools with close ties to 19th century figures who profited from oppression, enslavement and colonization — Lord Dalhousie and Egerton Ryerson, respectively. Both schools are coming to terms with these histories. They are establishing scholarly panels and a consultation processes with aggrieved groups, that can address colonial, racist and ableist attitudes, policies and practices.

University archivists, librarians, researchers and administrators across the country should work with communities to find meaningful ways of making their archives accessible to those targeted by destructive ideas and practices. Uncovering hidden stories of the past calls into question our ways of doing things in the present; for aggrieved and justice-seeking groups, an open past opens up more just possibilities for the future.

Evadne Kelly, Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Guelph and Carla Rice, Professor and Canada Research Chair, University of Guelph

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.