What’s in a Nickname? From Caligula to Sleepy Joe

Donald Trump’s habit of bestowing nicknames on his rivals in politics and the media is by now notorious. Wikipedia has a helpful page listing well over a hundred of them. Lyin’ Ted, Little Marco, Rocketman, and Pocohontas: they’re all there.

Why does Trump do this? We may think it is a way to grab attention, sort of like suddenly announcing that you want to buy Greenland. But my study of politics in ancient Rome – which was rife with nicknames – suggests something more. Using nicknames helps you to control the narrative.

Nicknames come in many forms. A common type is a shortening of a person’s name, like Abbie for Abigail, or JLo for Jennifer Lopez. Linguists often call this type of name a hypocorism, from an ancient Greek word meaning “child’s talk.”

The nicknames Trump uses are of a different, but still common, type. They are descriptive. They make a person seem more familiar to us by highlighting an important trait. Old Blue Eyes or Good Queen Bess are examples of this sort of name.

Even Homer used phrases like these to liven up his epics. Achilles is the Swift-footed One, Odysseus the Sacker of Cites. And as linguists Robert Kennedy and Tania Zamuner have shown, descriptive names like this are common among sports fans. Think the Sultan of Sweat, Air Jordan, the Great One.

All types of celebrities are given nicknames by their admirers or critics, especially in the media. Leona Helmsley was the Queen of Mean. Prince William is Wills.

Political campaigns also invent nicknames to make their candidates more attractive. Lincoln was already known as Honest Abe in 1860. But at the Illinois Republican convention of that year he became the Rail Splitter. This suggested his humble childhood in a log cabin and made him relatable to ordinary voters.

Trump is unusual among modern presidents in that he is the one to bestow the nicknames, almost always derisive, and he does so publicly, especially via Twitter.

Renaming somebody can be a source of power. In ancient Rome, the people, who had little recourse against overbearing emperors, could at least call emperor something by which they didn’t want to be known and dent their popularity. Nero was the Matricide, Commodus the Gladiator.

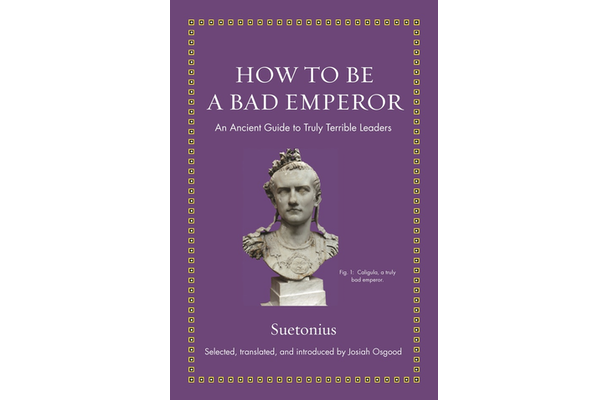

One of our richest sources for unflattering nicknames in Rome is Suetonius’ Lives of the Caesars, a set of biographies of twelve emperors, starting with Julius Caesar. It is thanks to Suetonius we learn that long before Tiberius became emperor, his army buddies spotted his love of drink and renamed him Biberius, playing on the Latin word “to drink.”

In incorporating unflattering nicknames, Suetonius, like other ancient biographers and historians, was able to present a negative view of the emperors he wrote about that is with us to the present day. This is controlling the narrative with a true vengeance.

The tradition about Caligula is a good example. The name Caligula itself was a nickname, meaning “little boot.” Caligula acquired it as an infant when he was displayed in his father Germanicus’ military camp dressed up in a miniature uniform, complete with soldier’s boots.

Like many since, as an adult he grew to detest his childish nickname. He wished to be known by such titles as Greatest and Best Caesar.

In calling Caligula by his nickname, later writers were refusing to let Caligula define himself. While given in childhood, “Little Boot” reinforced the idea that Caligula had no military accomplishments as emperor.

As Suetonius writes, when Caligula wanted to celebrate a triumph in Rome and had no captives to show in his parade, he rounded up the tallest Gauls he could find and made them dye their hair blond and grow it long to look like ferocious German warriors.

One interesting thing about Trump is that, other than The Donald, he has no particularly famous nicknames. Certainly in 2016 his political rivals did not succeed in giving him one. Rubio’s talk of “smalls hands” was a flop.

But Trump really doesn’t have a positive nickname either. Reagan is still warmly remembered as the Gipper. Similarly, when a Soviet newspaper dubbed Margaret Thatcher the Iron Lady, she shrewdly appropriated it for herself. It has stuck with her ever since – and certainly beats Milk Snatcher, the name Thatcher acquired when she abolished free milk for children as Education Secretary.

If Suetonius, who served on the staff of two Roman emperors, were alive today, I think he’d advise Trump to spend less time coming up names for others and think about what he could call himself.

Trajan, the first emperor Suetonius worked for, was called by the Senate the Best Emperor, optimus princeps. He is still called that today.

Josiah Osgood © 2020